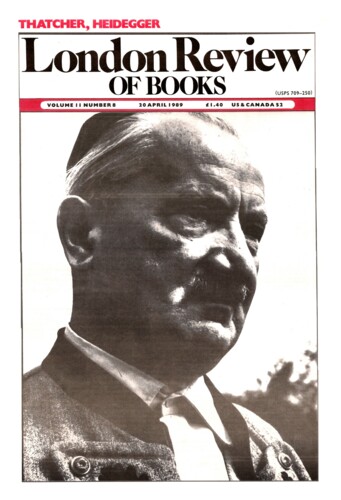

Professor Peter Gay is an eminent American cultural historian of German origin, an enthusiastic convert to Freudian doctrine, and an honorary member of the American Psychoanalytical Association – you can’t, as a warmly sympathetic biographer of Freud, do-better than that. The sheer amount of biographical, historical and psychoanalytical detail that has gone into the making of this Life is, as far as I can see, unparalleled in the literature of its subject; and so are the care and informed intelligence with which this stupendous mass of facts, conjectures and speculations has been sifted, as well as the attractive, good-humoured and unstrenuous way most of it has been presented. The book could have been shorter. Some of the bitter quarrels fought out in Freud’s circle of disciples, some of the tales of defection and betrayal, and some of the inconclusive arguments relating both to the most controversial of Freud’s publications and to his personal attitudes, are written out at greater length than seems necessary, and some quotations don’t improve by being repeated. But even where similar insights are presented more than once, the longueurs seem to be caused, not by a loss of narrative control, but by a scrupulous regard for fairness – fairness, one need hardly add, to Freud rather than to his adversaries. In one sense, the subtitle of the book, A Life for our Time, is justified. Professor Gay has been able to use a great deal more material than did Ernest Jones when he wrote his three-volume Life and Work (1954-1957). And as long as the guardians of Freud’s archives continue to exercise their censorship (which, now that scarcely any of the participants in this story are still alive, seems indefensible), this is bound to remain the definitive biography. In the bibliographical essays appended to each chapter Gay has indicated what the nature of the material still being withheld is likely to be, and how it may affect his own conclusions. (Thus one may infer from the evidence hinted at that Freud’s own sex life, which, it had seemed, came to an end when he was not quite 44 years of age, may turn out to have been less impoverished.) Gay is scrupulous in his affection, claiming to have preferred reasonable and probable conjectures to scandalously improbable ones. By and large, this is a remarkably accomplished and rounded portrait of the last Central European intellectual, and it seems unlikely that any future disclosures will greatly alter it.’

Freud: A Life for Our Time: A Life in Our Time by Peter Gay. Professor Peter Gay is an eminent American cultural historian of German origin, an enthusiastic convert to Freudian doctrine, and an honorary member of the American Psychoanalytical Association...