Eminent Athenians

Hugh Lloyd-Jones, 1 October 1981

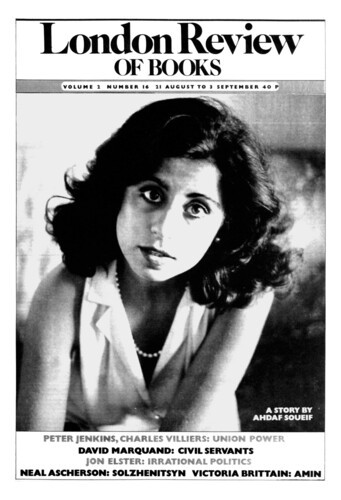

It is natural to contrast this book with The Victorians and Ancient Greece, by Richard Jenkyns, reviewed by me in the issue of this journal for 21 August-3 September 1980 (Vol. 2, No 16). Mr Jenkyns is a Classical scholar and a smooth and polished writer; I wrote that he ‘offers a great deal of information, clearly and pleasingly’. Professor Turner is a historian, the author of a study of the impact of scientific naturalism on Victorian England; he describes Macaulay’s style as ‘elegant’, and though he writes clearly enough, the adjective is not one that fits his own. He makes some mistakes which Mr Jenkyns would never have made; he cannot spell the names of Wilamowitz or de Quincey, or the word ‘Nicomachean’; he thinks Pindar was Athenian; he imagines that Frazer’s commentary on Pausanias, with its wealth of artistic, religious and historical detail, is a work similar to a critical edition of a text by Porson; and the knowledge that Exeter College, Oxford has a dining-hall, in which William Sewell once publicly burned a copy of Froude’s Nemesis of Faith, has led him to refer to it by the name of Exeter Hall, a building in London where Elderess Polly, Elderess Antoinette and other Nonconformist orators dear to Matthew Arnold used to edify the public. But where Mr Jenkyns is trivial, superficial and patronising, Professor Turner is serious, thorough and understanding. He is extremely well-informed, and, where necessary, well able to take account of Continental influences; and he knows how to detect and to delineate general tendencies. Jenkyns’s book is a pleasant entertainment for the casual reader, but Turner’s is an intelligent critical study of great value. It is handsomely printed, and the numerous misprints do not seriously impede the reader; and it is well illustrated, though I hope no future author will reproduce the ghastly portrait of Gilbert Murray by a relation which the National Portrait Gallery foolishly accepted.