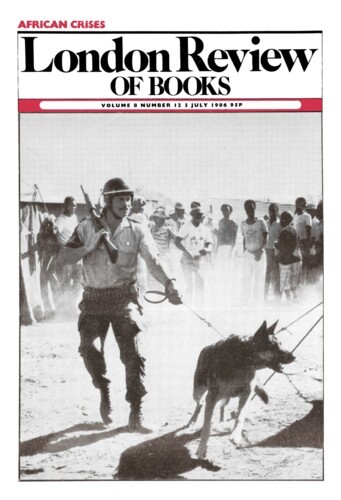

Afro-Fictions

Graham Hough, 3 July 1986

Three African writers, from very different parts of the continent – Saro-Wiwa from Nigeria, Ndebele from South Africa, Macgoye from Kenya. My ignorance of all three regions being deep and extensive, I am obliged to accept these three books in great part as documentary reports, as information about unknown ways of life. But perhaps this is right. One of the many problems for an African writer in the English language is the question of his audience. Who is he writing for? For his own people – for the small fraction of his own people who will ever be able to read him? Like Joyce, ‘to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race’? Or is it his task to inform the rest of the English-speaking world about a continent still dark to those outside it, about its hopes and its fears, its ambitions and its stagnation, its advance and its relapse? The latter must be a large part of his intention. Yet this confronts the reader with the social and political history of a hundred tribes and a dozen emergent nations of which in the nature of things the outsider can have only a faint and distant understanding.’