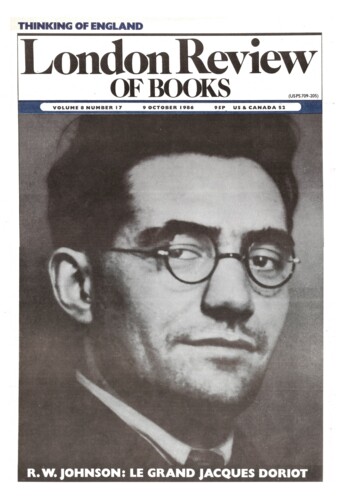

Trevelogue

E.S. Turner, 25 June 1987

Some writers have an unfair start in life. ‘When I was born, in July 1923, my mother was carried on a litter or “dandy” to the hospital by two murderers. My first ayah was a Burmese murderess called Mimi. Our servants were murderers.’ I do not recall Raleigh Trevelyan slipping this information into the lunchtime conversation when he was my publisher (a very helpful and tolerant one – interest duly declared). He was born in the Andaman Islands, the penal settlement run by the Raj off the coast of Burma, where his father, Walter Raleigh Trevelyan, was an Army captain. There may have been chain-gangs clanking away on the roads, and predatory savages on the neighbouring isles, but gracious living was not excluded: Government House had a ballroom the floor of which was polished by two murderers who held a third by the arms and legs and swung him up and down.’