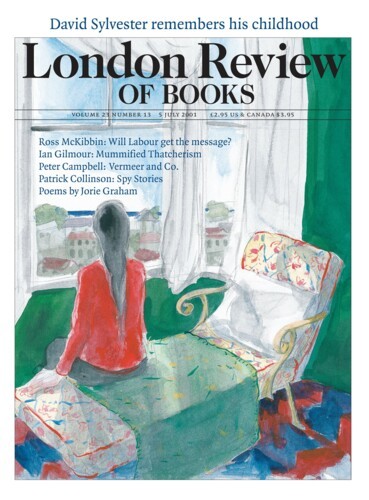

Memoirs of a Pet Lamb

David Sylvester, 5 July 2001

Icannot recall the crucial incident itself, can only remember how I cringed when my parents told me about it, proudly, some years later, when I was about nine or ten. We had gone to a tea-shop on boat-race day where a lady had kindly asked whether I was Oxford or Cambridge. I had answered: ‘I’m a Jew.’

A good deal of indoctrination must have gone into that. Did it come from...