Claude Rawson

Claude Rawson is a professor of English at the University of Warwick. His books include Henry Fielding and the Augustan Ideal under Stress and Gulliver and the Gentle Reader. He is editor of the Modern Language Review.

Richardson, alas

Claude Rawson, 12 November 1987

Richardson is the Hugo, hélas! of the 18th-century English novel, as Coleridge might have said: ‘I confess that it has cost & still costs my philosophy some exertion not to be vexed that I must admire – aye, greatly, very greatly, admire Richardson/his mind is so very vile a mind – so oozy, hypocritical, praise-mad, canting, envious, concupiscent.’ These sentiments of 1805 echo and reverberate through Coleridge’s Notebooks and Marginalia and Table Talk, as well as the Biographia Literaria, to the closing weeks of his life in July 1834. He brooded with fascinated revulsion on ‘the loaded sensibility, the minute detail, the morbid consciousness of every thought and feeling … the self-involution and dreamlike continuity’, like ‘a sick room heated by stoves’ contrasted with Fielding, who resembles ‘an open lawn, on a breezy day in May’.’

The night that I didn’t get drunk

Claude Rawson, 7 May 1987

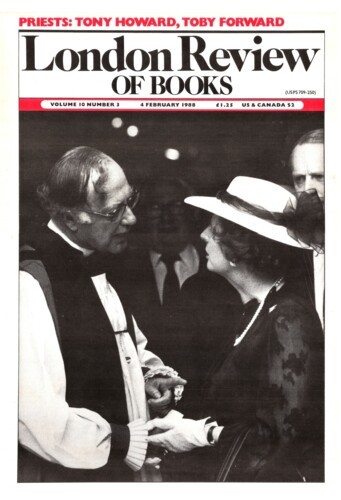

Boswell struts on. The English Experiment is the twelfth volume of his private papers to appear in the Yale Edition in the 37 years since the so-called London Journal 1762-1763 created its naughty little sensation. Only one more is due in the present series (there is a Research Edition too, but that is another and longer story), which will take us to his death, aged 54, in 1795. Perhaps the strut is becoming a waddle. The self-absorption and mediocrity of mind remain unabated, but he says that he’s ‘not so greedy of great people as I used to be’. This didn’t mean passing up the particular social opportunity then on offer, and later, when Mr Ramus the King’s page invited him to St James’s, he noted: ‘Formerly I should have jumped at such an opening. I am now too far advanced. Yet I may go.’ It’s like Crusoe feeling he can’t use the ship-wrecked money but then deciding to keep it, accelerated to the tempo of farce. One isn’t sure whether the social climbing has abated or whether a need to say so has developed: the distinction may be a fine one. Sometimes flagging energies merely take the form of talking about flagging energies.

Textual Intercourse

6 February 1986

Textual Intercourse

Claude Rawson, 6 February 1986

The title of John Fraser’s book comes from Hamlet’s most famous speech. ‘The name of action’ is what ‘enterprises of great pitch and moment’ lose when ‘the native hue of resolution’ is ‘sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought’: not, on the evidence of this volume, too much of a problem for Mr Fraser himself. His immediate target is litcritbiz, perennially anxious to demonstrate that books mean something other than what they say. He tells us that his ‘argumentative adolescence’, and his ‘apprentice years’ in the Sixties, were sorely fretted by Marxists, Freudians, irony-mongers and other assorted nuisances, restlessly disturbing the plain sense of things, while real life and Mr Fraser (‘human feelings and doings – falling in or out of love, fighting a war, and so on’) were taking their natural strong-willed course. For his own part, he has not, ‘at least since childhood’, been afflicted with that ‘sacred awe’ which is felt in France towards ‘the text’, and hasn’t much time either for ‘talk about non-referentiality and organic unity’. His own view, expressed in what is a fair sample of the delicacy of his idiom, is that ‘in distinguished literature the abstractions of ideologies were tested out in terms of the concretions of individual experience, rather than vice versa.’ He doesn’t like that academic ‘hunger … for metaphysics without ethics’ which ‘separates intellection from the demands of action’, and believes himself to be inhabiting a ‘Shakespearean world’ in which people derive their ‘images of future bliss or woe … from their past experiences, including their experiences of fiction, written or spoken’.’

Pieces about Claude Rawson in the LRB

A Spot of Firm Government: Claude Rawson

Terry Eagleton, 23 August 2001

It is remarkable how many literary studies of so-called barbarians have appeared over the past couple of decades. Representations of Gypsies, cannibals, Aboriginals, wolfboys, noble savages:...

Uppish

W.B. Carnochan, 23 February 1995

Item: in 1684, there appeared John Oldham’s posthumous Remains in Verse and Prose, with a prefatory elegy by John Dryden, ‘Farewell, too little and too lately known’....

Denis Donoghue writes about the Age of Rawson, and Rogers

Denis Donoghue, 6 February 1986

Now that the main ideas at large in the 18th century have been elaborately described, students of the period have been resorting to more oblique procedures. In 1968, in The Counterfeiters, Hugh...

Masters

Christopher Ricks, 3 May 1984

The life of Swift by Irvin Ehrenpreis is a great act of consonance. But one reviewer has deprecated the fact that Ehrenpreis does not write with Swift’s genius. So the first thing to say is...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.