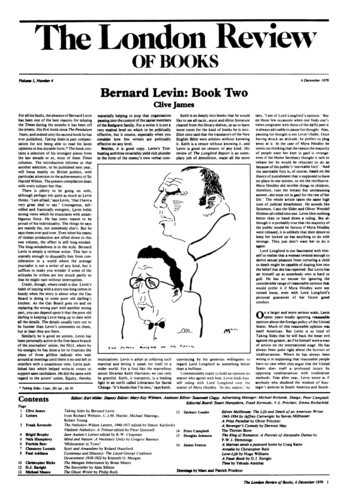

Triermain Eliminate

Chauncey Loomis, 9 July 1987

I admire mountain, rock and ice-climbing from a respectful distance. When young and foolish, I tried it. I even went up what some experienced climbers call ‘the milk run’ to the peak of Matterhorn, but that climb was my last: all the way up I visualised Lord Francis Douglas coming down the way that he did in 1865 – straight – and it spoiled the trip for me. Soon after I read a book entitled Alpine Tragedy. Its most telling point was made in a series of photographs of the great Alpine peaks: etched down their crags were dotted lines ending abruptly in horrid little X’s marking places where the various tragedies were simultaneously fulfilled and terminated. That cured me for good.’