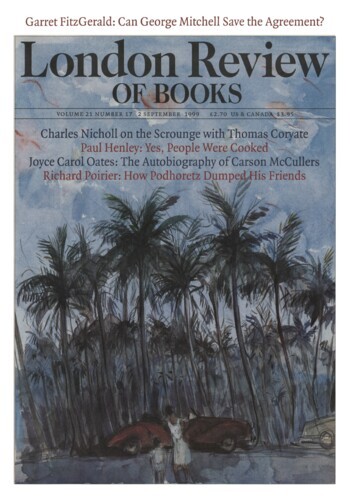

Field of Bones: the last journey of Thomas Coryate, the English fakir and legstretcher

Charles Nicholl, 2 September 1999

The old fortress city of Mandu stands high on a rocky plateau above the plains of central India. It is entered from the north; after a tortuous dusty ascent from Dhar, the road squeezes between two stone bastions and enters through the Delhi Darwaza, or Delhi Gate, where the remains of inset blue enamel can be seen on the dilapidated sandstone archways. Up this road and through this gate, on a day in late August or early September 1617, came the eccentric English author, polyglot and traveller Thomas Coryate. He was a smallish, bearded man with a long, rather lugubrious face – ‘the shape of his head’, according to one description, was ‘like a sugar-loaf inverted, with the little end before’. He wore simple native clothes, and was thin to the point of emaciation. He had travelled down from the city of Agra, four hundred miles to the north, and it is a fairly safe bet that he had done so on foot.’‘