Great Instructor

Charles Nicholl, 31 August 1989

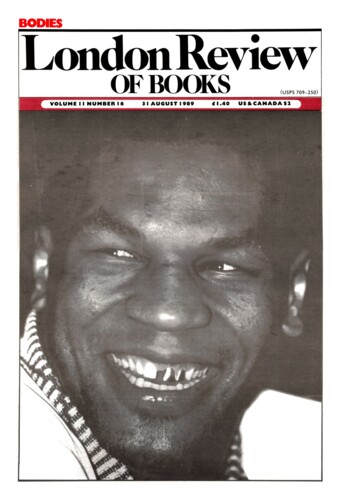

Ben Jonson is remembered as a master of English comedy, but you would hardly think so from his portrait. The earliest dateable likeness is the engraving by Robert Vaughan, done in the mid 1620s, when Jonson was around fifty. The face is jowly, bearded, dour, heavily lived-in. The shadowed eyes remind me of photos of Tony Hancock. Comedy, they seem to say, is no laughing matter. It was one of Jonson’s sayings that ‘he would not flatter, though he saw death,’ and his look seems to challenge the artist not to flatter him either. You can see the glisten on his skin from too much canary wine, and the warts and blemishes which more malicious caricaturists like Thomas Dekker dwell on: ‘a face full of pockey-holes and pimples … a most ungodly face, like a rotten russet apple when ’tis bruised’. You can confirm that, as Aubrey noted, he had one eye bigger and lower than the other. And you can guess at what was by then his vast bulk. In his youth he was tall and rangy, a ‘hollow-cheekt scrag’, but by middle age he had swelled to a corpulent 19 stone. In his poem ‘My Picture Left in Scotland’ (1619) he mocks his unwieldy frame –’