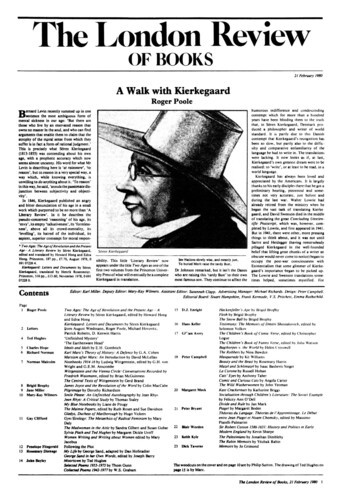

Leonardo’s Shortcomings

Charles Hope, 18 March 1982

The career of Leonardo da Vinci must be the most intimidating subject in the history of art. The paintings and preparatory drawings are a major topic in themselves, and any monograph on Leonardo the artist invites comparison with Kenneth Clark’s classic study, one of the best books of its type. Then there are the notebooks, a written legacy unparalleled in scale and range among surviving records of the Renaissance. The secondary literature is no less formidable, even excluding the many banal hagiographies and such eccentricities as the tedious claims of collectors to possess the original Mona Lisa. Simply to consult the facsimile of Leonardo’s largest manuscript, the aptly named Codex Atlanticus, in 12 vast and unwieldy volumes with an equally extensive commentary, is a major undertaking. Moreover, the recent scholarship on Leonardo, often of high quality, abounds with detailed observations and a mass of cross-references to one codex or another, but contains much less in the way of synthesis. To come to terms with this material requires not just time, but also the energy to master a whole range of subjects quite outside the bounds of conventional art history.