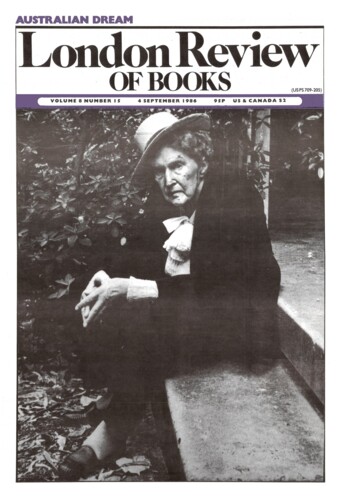

C.K. Stead writes about Christina Stead

C.K. Stead, 4 September 1986

In 1965, in London, I met Robie Macauley, editor of the Kenyon Review, who had accepted a story of mine. He asked was I related to Christina Stead. I had never heard of her. He told me she had written one of the great novels of the century, The Man Who Loved Children. When my story appeared someone wrote to Janet Frame recommending it. She wrote to say how much she’d enjoyed it but asking why I was now writing as a woman. This confusion was sorted out when I found that the next issue of the Kenyon Review contained Christina Stead’s novella ‘The Puzzle-Headed Girl’. Occasionally since that time I have been sent proof copies of novels by American women, with a letter addressing me as ‘Ms Stead’ and asking for pre-publication comment. Names, of course, are always more significant to their bearers than to anyone else. I like to claim the major Stead as my Great Australian Aunt.