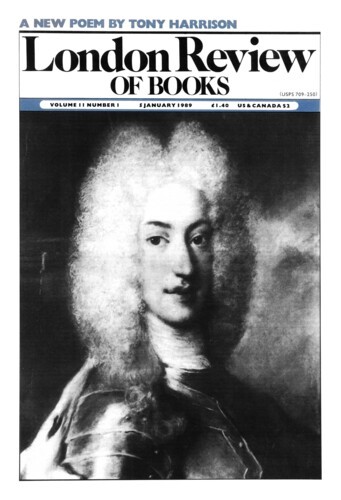

In the first book that Marx and Engels wrote together, The Holy Family, there is a passage about the Jacobin leader Saint-Just, who was famous not only for the ruthlessness with which he helped to conduct the Terror, but for the intensity with which he urged on the Revolution ideals of civic virtue drawn from the ancient world: his demand, as he expressed it, that revolutionary men should be Romans. ‘There is something tragic,’ Marx and Engels wrote, ‘in Saint-Just’s illusion. On the day of his execution he saw hanging in the Hall of the Conciergerie the great tables of the Rights of Man, and with pride and self-esteem declared: “After all, it was I who did that.” But those tables proclaimed the rights of a man who could no more be the man of ancient society than his national-economic and industrial relationships could be those of antiquity.’

In the first book that Marx and Engels wrote together, The Holy Family, there is a passage about the Jacobin leader Saint-Just, who was famous not only for the ruthlessness with which he helped...