Agnes Martin ’s lifelong dedication to simplicity of mind was perhaps made easier (it was certainly not impeded) by the faint trace of simple-mindedness in her nature. Had she not had about her a touch of the holy fool, the strange and specialised soul of a secular saint, her life and work would not have attained its compelling singularity. She famously said that the artist should paint with her back to the world. The world, meanwhile, was always ready to embrace her, and in the 1960s she was a successful member of the New York avant garde. But her centre of gravity lay way outside the bright metropolitan circle, and her renunciation of the urban scene, her turning away so decisively from social living, was only a matter of time in coming. Perhaps she had no choice but to follow her lodestar, but nothing should diminish her extraordinary courage in doing so. In 1967, with her reputation at its zenith, she lay down her brushes, gave away her painting materials, bought a pick-up truck and headed out West, telling a friend that she did not intend to speak to anyone for three years. After eighteen months, she came to rest on a remote mesa in New Mexico, twenty miles from the nearest outpost, with neither running water nor power, and built herself an adobe house, where she lived for the next ten years. She was 57. In 1971 she began painting again and continued without interruption until she died in 2004, aged 92.*

Agnes Martin stood (stands) apart. As if to acknowledge this, the Tate has chosen as the representative image for the present exhibition a black and white photograph of Martin standing alone in the scrub of New Mexico staring at the sky. We are to think of the life and the art as informing one another, this seems to say; and besides, it’s so much easier to awaken public interest through the story of the person – so sharply etched and arresting – than through the paintings, so elusive and hard to convey. You can see the problem immediately in the publicity material that does feature one of the paintings. Hoping to entice people with Martin’s work at its most sensuous, the Tate has chosen Friendship, a gorgeous expanse of gold leaf, 36 square feet of it, divided through scoring into 1776 rectangular panels, like some ancient oriental screen, glowing with a rich inner light, its patina mellow and tactile. When reproduced on a poster, everything wonderful about this picture disappears – its opulence, its largesse and supererogatory excess: of materials, of attention, of craft and labour.

It’s partly this problem of reproducibility that critics have in mind when they speak of Martin’s ‘invisibility’, partly that her pictures are next to impossible to describe and differentiate in words. To speak of graphite grids overlaid on washes of colour (the idiom of her first mature phase) or of horizontal bands and stripes of dilute acrylic in pale yellows, reds and blues, divided by weakly articulated rules (the idiom of her second) is to say nothing. While to attempt to account for the teeming variety of marks which the paintings disclose at close range would be as fruitless as to try to describe the disposition of pebbles on a six-foot square patch of sea shore. From the outset, critical responses to Martin’s work were positive, but the work itself didn’t carry beyond the exhibition space. If you haven’t actually seen a Martin canvas, you will always be hard pressed to understand what it can do. Martin once wrily remarked that she was the most frequently rediscovered artist of her generation. Even now, when there is no dispute about her place in the history of 20th-century abstract art, awareness of her comes and goes. On this side of the Atlantic, sightings of Martin’s paintings are as rare as golden eagles or Camberwell Beauties. (Of the more than a hundred works by Martin in the Tate exhibition, only seven are from public galleries in Europe). The present retrospective, at Tate Modern until 11 October, is the biggest ever to be mounted (after London it will travel to Düsseldorf, Los Angeles and New York) and the first opportunity in Europe to experience the range of Martin’s output since a smaller exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in 1993.

It is often remarked about our engagement with Martin’s paintings that we are uncertain, when standing in front of them, where they reside. There are said to be three basic viewing positions: up close, from a distance and halfway between. At a distance – so this account goes – the paintings hide from us, close like flowers at the end of the day, retreat into impassivity, their details no longer to be seen. Up close, the materiality of paint, graphite and canvas asserts itself: lines that looked straight turn out to be subtly irregular, the spacings of an intricate grid are discovered to be subject to slight deviations, uniform colour fields to reveal delicate fluctuations in density – thinning here, pooling there. In the intermediate position, meanwhile, everything starts to swim, shimmer and pulse. In fact, things are a little less neat than this. Some of the paintings actually become more emphatic and distinct as one moves away from them; others so dazzle at close range that focusing on the detail tires the eyes; a few remain visually stable wherever one happens to be standing. But generally, in their shifting, mercurial nature, their having no steady state, the paintings can seem to elude us. What they exactly are, we cannot grasp. A consequence of their indeterminacy is that the paintings ask that we look, look and keep looking. They beckon us into an attitude of attention, a willingness to take time.

Martin sought to create works that were without reference to the outside world. She was adamant that her paintings did not imitate nature: her grids, she insisted, bore no direct relation to the serried ranks of wheat fields in rural Saskatchewan (where she was born and grew up) or the map of Manhattan (where she first achieved fame), nor were her colours to be thought of in connection with the pale yellows, pinks and blues of a New Mexico dawn. What she painted, she said, were ideas – or rather, Ideas, in the Platonic sense: the very forms of Innocence, Perfection, Happiness, Blessing, Gratitude and Joy. She came to her pictures through inspiration, finding them, not in the world but in her mind, complete in all their detail. She then scaled them up to the size of her favoured format (a square, six feet by six feet; in her last years, five by five) calculating the proportions by means of a cumbersome, ad hoc arithmetic, according to rules of her own devising.

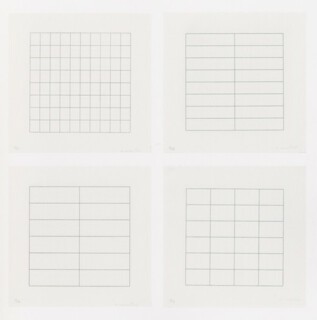

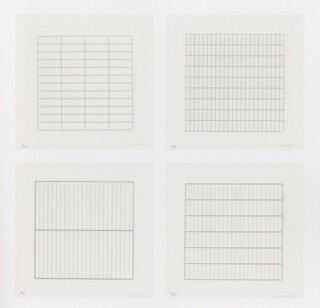

Martin thought of herself as an expressionist, but also as a classicist. Her paintings were about feelings, she said, but feelings of an impersonal nature. In 1971, she broke her four-year artistic fast with a set of screen prints under the title On a Clear Day. There’s nowhere in her oeuvre where the tensions inherent in her aesthetic creed are more sharply expressed. On a Clear Day consists of thirty simple line grids (each one foot square) printed on Japan paper. The prints were originally presented in a box and Martin did not stipulate the order in which they were to be shown. The grids are all different: some are loosely woven, some dense, some closed, some open. Five of the thirty are just sets of parallel horizontal lines, faintly suggestive of ideograms or characters from the I Ching. On a Clear Day throws down a quiet challenge: do we belong with those who find in it a cool and alluring openness or those who see it as merely vacant? Do we think of it as a work of sublime simplicity or semi-autistic blankness (I overheard a young man dismiss it with contempt as ‘an accountant’s wildest dream’)? Is it a call to contemplation or the occasion for a cursory glance before moving on?

Expressionist aesthetics have always banked on a lexicon of natural equivalences, between shapes and colours on the one hand, and qualities and feelings on the other. At the broadest level, it’s clear these equivalences exist (though what exactly they are rooted in may be conjectural): when Klee asks us to think of the struggle between an ‘aggressive straight line’ and an ‘intrinsically peaceful circle’, or the ‘victory of the fluid over the fixed’, we are happy to go along with him; there’s something more than just convention in the feeling that Rothko’s late paintings are sombre, melancholy, even tragic. Our language is saturated with unnoticed metaphor. Dark colours lead to dark thoughts, heavy shapes evoke heaviness of spirit; a splash of beige is unlikely to make us think of the sound of a trumpet.

Martin’s title On a Clear Day nudges us in a certain direction. When we look at the grids, we are to think of clarity and light. A clear day is a fine day and an unqualified good. It’s a day free of things that need doing, an open field of possibility, and it brings to mind ethical qualities such as truth and directness (we say of people that they are ‘honest as the day is long’, of things that they are ‘as clear as daylight’). For Martin herself, the grid was the foundation of her inspiration. ‘When I first made a grid,’ she wrote, ‘I happened to be thinking of the innocence of trees and then this grid came into my mind and I thought it represented innocence, and I still do, and so I painted it and then I was satisfied. I thought, this is my vision.’ Can it be ours? Martin believed the viewer created the work, yet evidently she hoped that what she put into her paintings we who look at them would, in some way, take out. In a short note – written, as she wrote all her lectures and commentaries, on a small piece of lined paper in her laborious longhand – Martin glossed On a Clear Day with instructions as to how we were to take it: ‘These prints express innocense [sic] of mind. If you can go with them and hold your mind as emty [sic] and tranquil as they are and recognise your feelings at the same time you will realise your full response to this work.’ The association of a grid with innocence, tranquillity, daylight, clarity and emptiness is not prima facie implausible (think of the lines by A.R. Ammons: ‘The noon sun casts/mesh refractions/on the stream’s amber/bottom/and nothing at all gets,/nothing gets/caught at all’) – yet the attributes of a grid are only sufficient for such an association, not necessary. We could think of a grid quite differently.

I’m not sure this matters. There’s no such thing as an unmediated encounter with art and, if our engagement with Agnes Martin’s work is richer for being given certain guidelines, so be it. In any case, nothing before or after On a Clear Day poses the expressionist conundrum quite so starkly. The generosity of the paintings (their size, colour, texture and luminescence) makes them sufficient unto themselves. At the same time, their expressive language is for the most part pretty self-evident. With the exception of the few black shapes that made their appearance at the start and the end of her painting life, Martin’s palette is airy and light – neither heavy nor dark – and it’s no stretch to associate this with the classicism she espoused or with the ideas of perfection and joy and innocence, and so on, which held her rapt.

Martin’s life and work are full of interesting contraries. Here was an artist who abominated intellect, yet who buttressed her work with her own home-grown system of ideas; a person who fought the demons of pride and the ego like the heroine of a protestant epic, yet ended up the centre of a minor cult; who turned her back on the world, yet loved nothing better than to drive a fast car; whose psychological vulnerability was extreme (she suffered from schizophrenia all her life, yet never painted when she was ill) but who was capable of uncommon feats of independence and self-sufficiency. Martin possessed an extraordinary integrity and imparted this to her paintings in the strangest way. On a Clear Day gives us a glimpse of what might have happened had Martin been more literal in the pursuit of her vision. It’s the most perfectly executed of all the works in the Tate exhibition and the one which, by its very nature, is reproducible. But it stands in relation to the paintings that came before and after it rather as a piece of Schenkerian analysis stands in relation to a Beethoven sonata – it’s a kind of study, a statement of the deep structure of the artist’s inspiration. The paintings themselves pursue their vision of innocence and perfection through means that ensure that they are never imprisoned by this vision. The densely packed grids that Martin set herself to draw across 36 square feet of canvas, using only a metal ruler and some masking tape, could not by that method be executed without random blemishes and unevenness. No human hand could be so steady as to place the pairs of painted dots that bead and stitch the intricate lattice at the centre of her painting Islands (1961), or the thousands of tiny tessellations in A Grey Stone (1963), without each dot, each tessellation, having its own accidental character. When she painted the wide acrylic stripes of her later paintings, Martin did so with free, unfussy brush strokes, unconcerned by the variable density of the paint as it was applied or the occasional overlap with the lines that divided the stripes. The result is an art that submits perfection to the realm of chance, an art that not only cannot be reproduced but not even copied – an art as far from commodity as it is possible to get.

Martin’s aesthetic of light and joy achieved its most radiant expression in her masterpiece The Islands of 1979, a set of 12 identically sized white paintings (six feet by six feet) to be hung together in their own space: Martin’s answer to the Rothko Chapel. This is the climax of the Tate exhibition, its effulgent heart, the work around which everything else arranges itself. The éclat of these paintings is at first almost uncomfortable, as though one had emerged from shade into bright daylight (the transition from the adjacent room, hung with Martin’s beautiful 1980s studies in the middle greys, is particularly powerful). As one’s eyes adjust to the brightness, the impression of uniform whiteness softens and breaks up and one begins to discern shapes, lines and colour (hardly more than an intimation of blue). The pictures do not so much reveal themselves as rise and fall, floating to the surface of perception and sinking back again. Like the leaves coming into leaf in Larkin’s poem, these paintings unfold ‘like something almost being said’. The compositional elements are the same in each painting: horizontal bands of dilute acrylic, of different widths, articulated by variably faint graphite rules, sometimes single, sometimes doubled into gutters of less than half a centimetre wide. The longer one stays with these paintings, the more the relationships between them multiply as one becomes sensitive to the delicacy of distinctions within the extreme and specialised semantic scale. Although the Tate exhibition is broadly chronological in arrangement, The Islands is the place to start, since prolonged contemplation of these pictures tunes one’s awareness to the right wavelength. Afterwards, one sees so much more in everything else.

‘Two paradises ’twere in one/To be in paradise alone’: Andrew Marvell’s lines from ‘The Garden’ could have been Agnes Martin’s epitaph (three of the works on show at the Tate are called Islands or The Islands). For her, separateness and solitude and silence were the essential preconditions of being in the world. They made her artwork possible, but they were also what her artwork sought to express. On my second visit to The Islands, after I had spent about 15 minutes there, first one, then another acquaintance whom I hadn’t seen for a while came up to me to say hello, breaking the spell. Martin regarded interruption as a scourge. People – even pets – were to be discouraged. When you go to Agnes Martin at Tate Modern, go alone.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.