I got to know Karl Miller in the 1960s, when I was in my mid-twenties and he was in his early thirties. He was the literary editor of the New Statesman and I was a junior editor – ‘a young editor here’, my boss used to say – at Faber and Faber. I didn’t know him well – a friend of mine, Francis Hope, was his assistant – but I talked to him at parties and once or twice I had lunch with him (I remember being told to eat my meat). He was a charismatic figure, tall, fair, slim, nattily dressed, flirtatious and a little wayward – a head-spinner. But severe too. You minded your words and that was part of the attraction. When he gave me a book to review I thought my life had met its moment. The book was by Chad Varah, the founder of the Samaritans, and it’s the obvious thing to say but true: I really thought my life would end, that I would have to end it, if I couldn’t get my sentences sorted.

Eventually I sorted them and took the piece to the Statesman’s office in Great Turnstile. When Karl had read it he said: ‘You’re a writer now.’ He was liable to make patriarchal remarks of that kind, and for better or worse – either way it’s a confession – I was very susceptible to them. When he gave me a second book and asked me to add a sentence at the last minute and I demurred he said: ‘You’re a journalist now.’ In his eyes it was a thing to be proud of, a calling of sorts. ‘You’ll be the laughing stock of Fleet Street,’ he used to threaten at the LRB when he thought someone had made a stupid suggestion, though by then the reference to Fleet Street just seemed quaint. (When at a later point I decided that I wanted to give up being a journalist and go to medical school instead he was nonplussed.)

Things weren’t going well for him at the Statesman. At some length he told me that there were tensions between the front and the back half of the paper; that Victor Pritchett, one of the Statesman’s directors, had said he wanted to have supper with him, and did I think that was a sign that he was about to be sacked? This went on for a bit and after a time, not knowing what to make of it all, I said what was really on my mind: that I hoped he wouldn’t have to leave before my review was published. I was never entirely forgiven for that.

Karl was much given to leaving – ‘more of a born leaver’, he said of Robert Lowell, whose wife had made the mistake of calling him ‘a born joiner’. He started at the Treasury, had a short stint in television; became literary editor first of the Spectator, then the Statesman; joined the Listener as editor in 1967 and the English Department at UCL seven years later; in 1979 he founded the LRB. Those were all jobs he left, sometimes in a huff. ‘It isn’t easy, resigning,’ he said on resigning from the Listener, ‘and the sympathy you incur is more alarming than the suspicion.’

I don’t think he was sacked from the Statesman but it’s true that he didn’t get on with the editor, Paul Johnson, and some months after his dinner with Pritchett he left. Either then or a few months later he was offered the editorship of the Listener. Not long afterwards I saw him at a Faber party; he mentioned the Listener and said that there might be a job there for me; if I walked up the road with him to the bus stop he would tell me more. He said he’d wait by the front door while I collected my stuff but when I returned with my stuff he’d gone. That was it, I thought: obviously he’d changed his mind – who’d want to give a job to someone with so little sense of what mattered? His impatience, my lack of faith – neither was untypical. The job, it turned out (he rang the next day), was to be acting deputy editor of the paper while the real deputy editor was on secondment, as they used to say at the BBC. The real deputy editor was Oleg Kerensky, Alexander Kerensky’s grandson. The connection with world history made the thought of the job even more alluring – something to report to my father.

The war had been the Listener’s heyday; in the 1940s it had a circulation of 100,000 or more; and, like the Third Programme, which provided most of its content, it was taken to represent British culture at its high-minded best. In peacetime the readership declined and Karl was brought in to give the paper a whiff of the 1960s and, with luck, arrest the slide. We occupied a series of rooms along a corridor in what is now, and had been before it was requisitioned in 1939, the Langham Hotel at the bottom of Portland Place. The original hotel had been a grand establishment and our offices came in two sizes: single bedroom and double bedroom with bath. We didn’t have much sense of being part of the BBC; it was the Listener that counted. And if from time to time we had a run-in (a word Karl used a lot) with one producer or another it never amounted to much. In the middle of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, for example, we declined to publish an interview with King Hussein that had been obtained with great difficulty in favour of a diary from a reporter who lost his nerve and spent several days – or maybe it was just hours – cowering in his hotel bathroom. That was the sort of thing the high-ups didn’t like. (Local colour: Karl and I didn’t agree on the spelling of King Hussein’s name – should it end in ‘ain’ or ‘ein’? I rang the Jordanian Embassy: ‘ien,’ they said. I said: ‘Are you sure?’ ‘Of course,’ they replied: ‘i before e except after c.’)

After a few months Oleg Kerensky found something else to do and my temporary job became permanent. It lasted six years. At the end of 1973 Karl resigned because of what he felt was a lack of support on the part of BBC management. I didn’t altogether see it that way but maybe I didn’t know enough. In any case I owed Karl the job and I followed suit. After the Listener I worked at the TLS. It was fine, it was a good paper and it was a job. But working with Karl was much more than a job; a day at the front rather than a day in the office. Everything mattered intensely, every detail, every word split.

One summer when Karl was away we carried an interview with Penelope Betjeman, Betjeman’s rather horsey wife. Thinking to preserve her manner of speaking – the interview was transcribed from television – I’d allowed her to carry on saying ’cos (instead of because). Karl was away for three issues; the only thing he said to me on his return was: ‘Those cos-es caused me nearly to be hospitalised.’ Legend has it that once on holiday from the New Statesman he’d wrapped himself in a rug and rolled on the floor groaning when a copy of the first issue produced in his absence arrived at the house where he and his family were staying.

Karl said many harsh things but with luck it was less the pain or the injustice that you remembered than the wording or the syntax (‘nearly to be hospitalised’). People who knew Karl reported his turns of phrase to each other (of ME, a fashionable condition in the 1980s: ‘that disease where your wrists go numb from carrying money home from the bank’; a contributor asks, ‘I don’t suppose there’ll be any money for flying anywhere,’ and Karl replies, ‘I’m afraid not unless you get on my back and I start flapping my hands’; ‘I don’t demand that he experience having his arse shot off. I just note that he didn’t’; ‘when you compare Graves with Wordsworth or Rilke you are comparing a rearrangement of the room with a subsidence of continents’; of the 1987 hurricane to a contributor in California: ‘every second tree in the square is on its knees’). In that sense he was the object of a cult of an Oxbridgey sort, which he wouldn’t have liked, committed as he mostly was to more egalitarian notions. Wouldn’t have liked but also would have liked; committed but not exclusively; there were few issues about which he didn’t have two views.

In the 1980s he published a book called Doubles on the literature of duality, and many of the pieces he wrote for the LRB were taken up, directly or indirectly, with the idea of division. (He was a reader of signs and in the year Doubles was published a novel came out entitled The Doubleman, which featured a character called Karl Miller. ‘It’s a small world, and a double one,’ he concluded, well pleased, in an LRB Diary.) The propensity to see writers and their work in terms of dark and light, night and day (and not only writers: ‘ghosts are creatures of habit, and of Hamlet’), and to seize on any pairings that offered themselves (‘his antagonisms and his ingratiations’ – of James Kelman; ‘drugs … poured their balm, but embalmed him’ – of Robert Lowell; ‘Emmas, Cockburn and Rothschild’ – a Listener cover line; ‘Gray’s Elegy, and Wynne Godley’s’ – an LRB cover line), was always there but became more pronounced with time. To an extent it was playful, as always with Karl; even his rages were playful, as long as you kept a straight face – that was part of the pleasure of working with him. Of a contributor who said something disobliging: ‘If that man comes in here again I’ll kill him.’ And then because we smiled: ‘No, I mean it – I’ll kill him.’ He meant what he said and he didn’t.

Singlemindedness, a mind that knew its own mind, obviously wasn’t a good thing in his eyes. Clarity was something one could have too much of and a piece might be denounced as ‘culpably clear’, which usually meant that the author was too sure of his case. A position had to be argued for – stating it wasn’t enough; questions had to be asked, reputations disputed. Spelling things out: that too could be a defect. Reduced to basics, a notion loses much of its interest. Yet he liked pieces that didn’t hedge their bets, that had a point of view and an attitude and – as his pieces did – their own way of saying things (of Ford Madox Ford, Clive James wrote in the Listener, ‘the grade A crumpet came at him like kamikazes’). He said he would publish anything as long as it was interesting though I don’t think that was ever put to the test, or not directly. But for several years we didn’t review any books on the Soviet Union in the LRB because we couldn’t find a reviewer whose approach we liked. He wanted the people he worked with to speak up, to say what was on their mind; and in theory there was no point in having colleagues who didn’t, but it was often hard to know whether one was speaking up or speaking out of turn and getting it wrong could bring the working day to a close. Silence wasn’t really a solution. Karl had a poor view of Cordelia, as he liked to remind me.

In the summer of 1979 the New York Review decided to launch a British version of itself and Karl was to be the editor. The Times and its empire, which included the TLS, had been off the streets since the beginning of the year as a result of its owners’ dispute with the unions and the idea was to fill the gap left by the absence of the TLS. Susannah Clapp, who’d also been at the Listener, was the assistant editor; I was to be Karl’s deputy. The first issue of the new paper, designed by Peter Campbell, another refugee from the Listener, appeared at the end of October; a month later the TLS was back; and the following spring the New York Review let us go our own way.

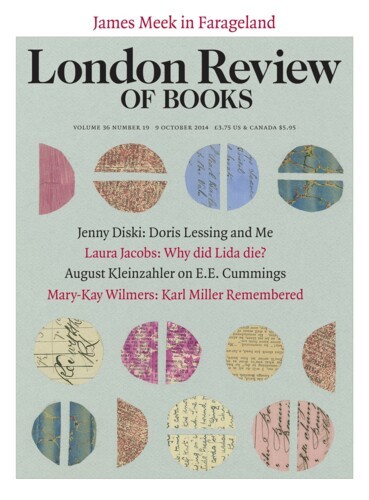

The LRB became a paper in its own right in May 1980, when the first independent issue appeared. (John Lanchester will write about Karl and the LRB in the next issue.) For all its genius Karl’s Listener was still a conventional London weekly, though affiliated to the BBC, rather than a political entity of one sort or another. The LRB is more sedate (no comic strip), a consequence of its origin as an offshoot of the New York Review, of the length of the pieces and of Karl’s position at UCL, but also less circumspect, free to be bad-tempered – angry if you prefer – and free to be carefree. William Empson, ostensibly reviewing the Arden edition of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the very first issue, was mainly concerned with calculating the speed at which the fairies travelled (800-1000 mph) to stay ahead of daylight. A paper starting from scratch can choose the space it wants – or would like – to occupy in the world. I’d like to think this is still very much Karl’s paper, word splits and all.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.