Pauline Boty, the only prominent female Pop artist among a generation of famous men, was a blonde beauty, described as a ‘goddess’ and likened by contemporaries to Brigitte Bardot. Others disagreed: she was more like Simone Signoret. ‘There were other beautiful girls who could paint at the time,’ the architect Edward Jones recalled, ‘but none who were quite as wonderful as her.’ She had an acting career on the side, including a bit part in Alfie. She was almost cast as the lead in Darling, before Julie Christie came along. She danced on Ready Steady Go!, modelled for David Bailey, introduced Bob Dylan to London, broke Peter Blake’s heart, was part-owner of a frock shop in Carnaby Street, married and gave birth to a daughter all before dying in 1966 at the age of 28. Her story was remembered but her pictures weren’t: most languished in her brother’s garage until a Pop Art show at the Barbican in 1993 led to the Tate’s buying one (The Only Blonde in the World). And a few have recently resurfaced thanks to the Wolverhampton Art Gallery’s offensively – or merely ludicrously – titled exhibition Pauline Boty: Pop Artist and Woman, now on show at Pallant House in Chichester (until 9 February).

The paintings start with an oil self-portrait from 1955, when she was a 17-year-old just enrolled at Wimbledon School of Art. There, she attracted a lot of attention. When a male student sitting opposite her in the canteen asked her why she wore such bright red lipstick, she lunged forward, saying: ‘To kiss you with!’ But there’s nothing flirty about the picture: her hair is pulled back, she has staring, serious eyes, an unsmiling mouth and a slightly too large nose. She went on to the Royal College of Art, joining the School of Stained Glass because she’d been told that, as a woman, she didn’t stand much chance of getting into the prestigious School of Painting. There’s an example of her stained glass work in the show: a fractured city below, including a Notre-Dame-like façade, and a floating woman above, eyes closed, with red roses – an emblem Boty clung to – worked into the space around her head and body. Stained glass allowed her to make images that looked like collage, a form then very much in vogue: Richard Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi had shown at the Whitechapel in 1956, incorporating pictures of movie stars, images of food packaging, snippets of consumer advertising. Boty made collages without support or encouragement from a tutor: one from 1959 shows a classical female hand holding a bar of Pears soap over some cut-out pictures of roses, an image of a clock, and a tuxedoed all-male orchestra posing for the camera. It’s not much to look at.

There were other extra-curricular actions too. In her first term at the RCA she became a founder member of the Anti-Ugly Action Group, which opposed uninspiring new London architecture. The organisation carried out performative demonstrations, including carrying the coffin of British Architecture to the headquarters of Barclays Bank, where Boty lit candles and sprinkled rose petals. The Daily Express ran a piece on her, accompanied by a large photograph with the caption: ‘Of all things she is secretary of the ANTI UGLIES.’ The article begins: ‘Miss Pauline Boty assured me that it has nothing to do with policy, which is far above these things. But the fact remains that 20-year-old Miss Boty … is, well, very pretty indeed. As you can see from my picture.’

Stained glass wasn’t where things were at at the RCA. In 1959 David Hockney, Derek Boshier, Allen Jones and Peter Phillips were all enrolled at the School of Painting; Patrick Caulfield joined a year later. Boty socialised with them all outside class, but unlike them wasn’t always selected for the better student exhibitions. Things changed rapidly after she left, when her old tutor from Wimbledon invited her to exhibit at the AIA Gallery in a group show. Blake, Boty, Porter and Reeve opened in November 1961 and included twenty pieces by Boty (many now lost). The titles were all very Pop-y: Is It a Bird, Is It a Plane?; Goodbye Cruel World. Her work got the most space in the write-ups: the Observer praised her ‘suitably pretty wit with evidence of imagination more lasting’. (There was no getting away from her prettiness.)

In 1962, Ken Russell profiled her alongside Boshier, Blake and Phillips in his documentary Pop Goes the Easel, made for the BBC’s Monitor series. The camera enjoys lingering on Boty: there are lots of shots of her in her fur-collared coat, wandering down Portobello Road market or playing in a fairground with the three men. She is what everyone wanted a 1960s girl to be – within a few years there would be a thousand like her. The male artists talk formally about their work and influences, but the section of the film dedicated to Boty opens with a dream-like sequence of her running down a corridor being chased by a woman in a wheelchair. Boty wakes from the nightmare in bed wearing a nightie and eye make-up. She lets the three men into her Notting Hill flat, where they sit around drinking the coffee she makes them. We get a brief insight into her work when she goes through a stack of her collages with Blake, rather teasingly. (Blake was in love with her, and gave her a picture, Valentine, made up of collaged Victorian valentine cards and one of his signature hearts.) An extended scene towards the end shows the artists doing the twist. Surrounded by other dancers, Boty winks knowingly at the camera when it zooms in on her; later, she shimmies about with a fur stole.

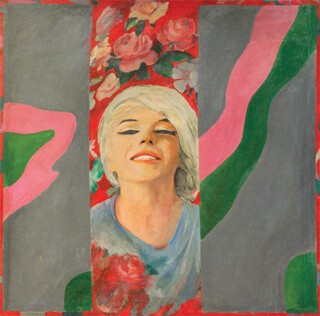

Two of Boty’s paintings of Marilyn Monroe are in the show – the only really good things there. Colour Her Gone was made after Marilyn died: Boty copied the face from a photograph that appeared on the cover of Town magazine in November 1962. Soon afterwards she posed for a picture in ARK mimicking the look, with heavy black eyeliner and mascara, hair swept into the same style, a slight smile on her lips, face tilted upwards, eyes almost shut like Marilyn’s. In Boty’s painting, Marilyn is boxed in by grey panels; she looks up at the viewer from a background decorated, yet again, with roses. In The Only Blonde in the World, which she made in 1963, the panels are green. This time Marilyn steps out boldly, wearing white fur.

In the summer of 1963 Boty met Clive Goodwin, a literary agent and radical of the New Left, later one of the founders of Black Dwarf. Boty had been having an affair with a married director, Philip Saville, which was getting her down (she felt, she said, that he kept her in a box, occasionally lifting the lid to take her out). She was introduced to Goodwin in the street by a friend and married him ten days later. He was ‘the first man I met who really liked women … a terribly rare thing in a man’. They moved to a flat on the Cromwell Road and installed a garden swing seat in the living room. Everyone hung out there: critics, poets, left-wing playwrights and artists. Boty made a picture called Cuba Sí, in collage and oils, showing a woman dreaming of the revolution. In 1965 she discovered she was pregnant. At an antenatal check-up a lump was found and she was diagnosed with cancer. She refused treatment, as it might have harmed the baby. She tried to keep things going and – Frida Kahlo-like – painted and sketched sitting up in bed. The last work she made was called BUM, a brightly coloured painting of exactly that, under a proscenium arch, created for Kenneth Tynan’s revue Oh! Calcutta! (or ‘O quel cul t’as!’). Her daughter was born in February 1966 and Boty died five months later. Clive Goodwin died in 1978 in LA of a cerebral haemorrhage. He collapsed in the lobby of the Beverly Wilshire – he’d been meeting Warren Beatty to discuss the script for Reds – and the hotel staff, thinking he was drunk, had him taken away by the police: he died in a cell. Their daughter, Boty Goodwin, who inherited her mother’s looks, got $500,000 compensation in an out-of-court settlement. Later, she used some of it to pay for art school in California but died of a heroin overdose in 1995, at the age of 29, a year older than her mother.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.