You could mount an exhibition entitled ‘The Moment of Edvard Munch’. It would focus on the Norwegian who first hit Paris in 1885, aged 21, and who, energised by his immersion in contemporary French painting, became a linchpin of the Berlin avant-garde of the 1890s. A gatecrasher to the metropolitan party, playing havoc with its pictorial etiquettes – that might be the drift. (‘The wild man of the north’, the Germans liked to call him.) In among modern art’s late arrivers (like Gauguin, not committed to painting until he was nearly forty) and passersby hauled inside (like Henri Rousseau), Munch would be one more newcomer embraced for his outlandish, provocative mangling of the existing guidelines for belle peinture.

Munch did come to Paris with some training, but in genres appropriate to provincial Kristiania, each of them distinct: the frontal portrait, the landscape pochade, the bourgeois interior. His characteristic impulse after his exposure to Paris and to Symbolism was to scrunch them together. The figure and the scene it occupied were thrust into an abrupt unity as if by pressure from behind, a paroxysm that pervaded the whole canvas. What was arrestingly uncouth was the brutality of Munch’s fusions. The slashes, bands and swoops that structure his images, along with the ferocious all-over thumping his brush dealt the canvas, opened up a new style in declamation. This combined with a canny instinct for the reproducible. An exhibition fixing on this juncture, where so much in the next century’s art swings into view, might start with The Sick Child of 1886 but would focus on Munch’s run of iconic inventions from around 1893 – Puberty, Madonna, The Kiss and of course The Scream.

Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye (until 14 October) goes out of its way not to be that show. Its curators, Clément Chéroux and Angela Lampe from the Centre Pompidou, have put on a capacious display, informed by a mission to explain. But the argument that drives them is internal, aimed at previous curators’ preconceptions. Munch, they point out, spent sixty years hard at work, dying in 1944, an honoured if solitary national monument. Even during his reckless, bohemian 1890s, while press denunciations and exhibition closures whizzed around him, the Norwegian government was funding him and the country’s national gallery was buying his work. The brawling drunk who went into rehab in 1908 came out a Knight of the Order of St Olav. What this Scream-free exhibition invites us to think about is the relation between psychodrama and longevity: how to sustain, year in, year out, a state-approved convulsion of the soul; how the relentless acceleration of ‘the modern eye’ can settle into a kind of stasis.

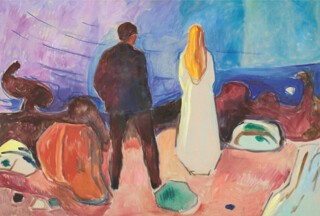

Chéroux and Lampe rub our noses in repetition, presenting, for instance, not the searing, stricken The Sick Child of 1886 – Munch’s memory of his sister’s death – but re-performances from 1907 and 1925. The victim of trauma gets recast as a ham obliging popular demand – rather slackly, at that. The curatorial critique of originality does however make you notice the way Munch’s palette shifts from fin de siècle late evening violets towards janglier oranges and browns. Another image first coined in the 1890s, The Lonely Ones – a man and woman staring out to sea – becomes wholly detached from perspective three decades on, emerging as a thrilling surface improvisation of stains and stabs, as singing and raw as anything in modernist painting. Here the conviction of Munch’s performance may sag, there it may sharpen: the quality follows no consistent arc.

He comes across as a quickfire but resourceful workman, kept busy by his progressive-minded patrons. A 1917 portrait of a government lawyer slickly appropriates newfangled Cubist faceting. A huge study for a still huger Sun of 1911, a blast of bombast destined for a university aula, also shows a smart tactician at work, restaging the light’s rainbow impact in carefully plotted blurts. Munch’s sun is ‘in’ his eyes in the same way a haemorrhage is ‘in’ his right eye in a later set of studies, which record the bizarre way it affects his visual field: his working premise is that within and without no longer have fixity for the modern artist, for whom all is subsumed within electromagnetic ‘vibration’. (The catalogue describes him as an avid consumer of the pop science of the day.*)

The position of this mature Munch, this accredited angst-monger, is itself faintly bizarre. An uproarious canvas from 1932 remembers a fistfight he got into long before with a fellow Norwegian painter who’d impugned his patriotism at a midsummer party. ‘We both ended up sprawled on the slope beneath my house – he bloody in his white suit, me reeling and winded’ – so the picture tells you, its hot browns joined by emeralds, blues and brilliant pinks in a rush of stutters, stains and swipes. It declines to communicate what provoked the scrap. In fact its raison d’être is entirely, defiantly: ‘This happened to me. It was a shock. End of story.’ As if that were the bottom line in the life of this modern artist. As if there were no ‘as ifs’ at all, no metaphors or contexts to contain them: merely anomalous episodes of energy.

Relying on them, Munch sometimes burst through doors and sometimes bashed against walls. One display brings together six versions of a Weeping Woman he rendered around 1907 – each equally frantic, each equally inert. Why this subject obsessed him never emerges. This, I guess, is the level at which Munch’s repetitions retained authenticity: the option of redrawing his compositions was ruled out by his consigning all trust to the original inspiration. What memory only transmits vaguely should only be painted vaguely, his performances typically declare. What matters is the few essential outlines, at which the paintwork grips as if they were handrails in a mire – cloisonné turned claustrophobic.

There are some tremendous epiphanies, notably the Workers on Their Way Home of 1913, their heavy, angry bodies seeming to block and invade the viewer’s own body space. But the effect of constriction is magnified by the exhibition overall. Munch’s memory only transmitted within a narrow emotional bandwidth. Balefulness was his forte, and a score of shades of desperation and fury are evoked by the self-portrait canvases on view in Tate Modern, from the surly teenager of 1882 to the withered streak of personal persistence stood ‘between the clock and the bed’ a year or two before his death. The curators rather skew their fascinating revisionist exercise when they accompany these canvases with a plethora of self-portrait photographs. The space could have been far better used to focus on Munch’s lithos and woodcuts. The material resistances of printmaking interact with his peculiar energies magically, indeed positively deliciously, whereas with a Kodak he is little better than inept. Shot after shot of the stubborn old loner’s Mussolini chin and scowl translate the rat-in-a-corner predicament dramatised by his brush into something oppressive and banal. Sometimes you can have too much of a bad thing.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.