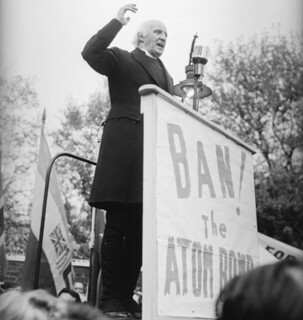

In his prime, Dr Hewlett Johnson was one of the most famous men in the world. Almost from the moment he was made dean of Canterbury in 1931, he became instantly recognisable everywhere as the Red Dean. His faith in the Communist Party, and in Stalin in particular, was unshakeable. Purges and famines, executions and persecutions passed him by. Though he never saw the need actually to join the Party, he remained a tankie to the last, until he was finally winkled out of the deanery in 1963, when he was pushing ninety.

The only occasion in his whole life when he admitted to experiencing doubt was in the early 1890s, when he was an engineering student at Owens College, the forerunner of Manchester University. He had retained the biblical certainties of childhood, and was knocked sideways by a lecture given by Professor Dawkins, the eminent Darwinian: ‘I turned from the lecture room with a passive face and a calm voice. But within there was tumult and utter darkness. The evolution theory was true – of this I was convinced. And it made the story of Genesis and the Bible false.’

We have barely recovered from this delicious coincidence of surname – the Dawkins in question was the geologist and palaeontologist Sir William Boyd Dawkins, not a direct ancestor, if ancestor at all, of the present carrier of the Darwin meme – before Johnson has recovered from his spiritual despond. In a twinkling he has reconciled God and Darwin. Thereafter his magnificent self-confidence never flags, his melodious voice booms on, wowing sympathetic audiences all over the world. In 1946, already into his seventies, he gave a prizefighter’s salute to a crowd of thirty thousand inside and outside Madison Square Garden, eclipsing Paul Robeson and Dean Acheson. An awestruck young Alistair Cooke reported in the Guardian that ‘he looks like a divinity and he looks like the portrait on every dollar bill.’ The resemblance to George Washington is undeniable, although there is a creepy hint of Alastair Sim too.

Never one to underestimate his own impact, he reported to his second wife, Nowell, that a colleague had said he was ‘one of three English public men who could command the greatest audiences everywhere.’ ‘I know it is true,’ he added, while dutifully sharing the credit between the Almighty and the Communist cause. He recorded in his autobiography that when he and the Marxist scientist J.D. Bernal were in an exuberant crowd at the World Peace Conference in Rome in 1959, Bernal turned to him and said: ‘Did you hear that, dean? They are shouting: “An honest priest, he should be our Pope.”’ It’s a thought that might well have crossed the dean’s own mind, feeling as strongly as he did about the imperfections of the Catholic Church, certainly as compared with the unimpeachable performance of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the CPs of China and Cuba too.

His self-assurance was anchored in a happy family, where untroubled faith went hand in hand with an untroubled income from Johnson’s Wire Works of Manchester. The firm was founded in 1791 and continues to this day as AstenJohnson, exporting papermaking machinery to 56 countries. Hewlett, born in 1874, felt quite at home with the paternalism which could flourish within a firm that remained in the hands of a single family, though he deplored ‘the harder and less human atmosphere’ which came with technological change. He didn’t disdain the Johnson’s dividends he received, or the settlement from his first wife’s father which came to him on her death.

During the General Strike, his sympathies were of course with the miners, though one of his uncles, Alfred Hewlett, was chairman of the Mining Owners’ Federation and another, William Hewlett, was chairman of the Wigan Coal Company. I am not sure whether the Hewlett brothers were included in Lord Birkenhead’s celebrated comment that ‘it would be possible to say without exaggeration that the miners’ leaders were the stupidest men in England if we had not had frequent occasion to meet the owners.’

In 1952, when many capitalists were still strapped after the war, Johnson owned four flats and three garages in Canterbury, two properties in the nearby village of Charing, two more in South-East London and a holiday home in North Wales, where Nowell and their two daughters had taken refuge during the war. He also possessed a nicely spread portfolio, which included holdings not only in Johnson’s Wire Works but in Lonrho, not yet unmasked as the unacceptable face of capitalism. The prize money of £10,000 (perhaps £200,000 in today’s money) from the Stalin Peace Prize which he had won the year before was icing on a substantial cake.

John Butler is a Canterbury man and an emeritus professor at the University of Kent, best known for his book The Quest for Becket’s Bones. The dean now and then compared his own struggles for truth with those of St Thomas, though the dean’s bones and indeed the rest of him are easier to track. But it was politics rather than saintliness which got him the deanery, through the rare coincidence of a Labour prime minister in the shape of Ramsay MacDonald and a leftish archbishop of York, William Temple. This is an excellent biography, crisp, sometimes cutting, but never less than fair and always as sympathetic as humanly possible to its subject even in his most maddening moments. Aided by access to the dean’s archive, Butler brings out all Johnson’s good humour and generosity of spirit. In everything bar his politics, he was a rather traditional Anglican dean, broad in his theology, simple in his faith. He enjoyed food and wine and family life, gave his money away to anyone down on their luck, believed that his cathedral should be a place of light and beauty, filled it with flowers and revived the choir school. Left to himself, he would have introduced incense too. He was also the first prelate since Archbishop Baldwin in the 12th century to argue that Canterbury should have its own university.

He was a brave and restless man, exulting in travel, adventure and his own celebrity. When the Germans repeatedly bombed Canterbury, he strode about the debris with relish, writing to Nowell that ‘I would not have missed this for anything … The Cathedral looks glorious without its windows.’ One is reminded of Churchill saying to Margot Asquith in the darkest days of the Great War that ‘I would not be out of this glorious, delicious war for anything the world could give me.’ On VE Day, the dean was in Moscow with Stalin. Two weeks later, he was among the first British observers to enter Auschwitz. He wrote about what he saw with a superb angry eloquence.

But there is no doubt that Johnson was gullible. Butler does not mention the period in the 1930s when he strode up and down the country preaching that Major Douglas and Social Credit were destined to ‘win the world’, until he discovered that Douglas had come out for Franco. Like many egomaniacs, he was extremely interested in his own health, and always ready to swallow the latest dietary fad. He was convinced that a Romanian doctor called Anna Aslan had discovered a drug, Gerovital H.3, which could reverse ageing and restore hearing loss. The drug turned out to be nothing more mysterious than procaine hydrochloride, now better known as Novocaine, the local anaesthetic used by dentists. But Johnson continued to swear by it until his death.

After he had swallowed something once, he never stopped taking the medicine. David Caute begins The Fellow Travellers: Intellectual Friends of Communism (1973) with the story of Hewlett and Nowell escaping from the World Peace Council and clambering aboard a local bus going they knew not where and Hewlett saying to the driver: ‘Tickets to the end of the line, please.’ And he toed that line all the way. Victor Gollancz, who published Johnson’s bestseller The Socialist Sixth of the World in 1939, tried to make Johnson add something critical about the Nazi-Soviet Pact, which had just been signed, but he merely blamed Finland and defended the pact as a regrettable but necessary expedient. After the war he gave evidence in support of French Communist journalists when they were sued by Victor Kravchenko for alleging that he had invented his stories of Christian churches being persecuted in the Soviet Union. In the same year, 1949, he sided with the Hungarian secret police when they arrested Cardinal Mindzenty on trumped-up charges of treason. Later on, he remained deaf to Khrushchev’s speech to the 20th Congress and defended the Soviet invasion of Hungary. Of all the rapturous moments he enjoyed in the company of the great, I would pick out his stay at the Havana Riviera hotel in the year after the Cuban Missile Crisis, when he was nearly ninety. At a glittering reception (there is a touch of Sylvie Krin about the dean’s memoirs – the receptions are always ‘glittering’, just as the women are always wearing ‘splendid gowns’), he met not only Castro but the ‘strong, vital, buoyant’ Che Guevara and ‘a lady with a sad, beautiful face’, whom he and Nowell recognised as Dolores Ibárruri, better known as La Pasionaria. He was among his own people, big people.

His admiration for Communism was inseparable from his worship of power. Not for nothing was The Socialist Sixth retitled The Soviet Power for the American market. Nettled by squabbles in the cathedral chapter, he put down the archdeacon by announcing that he was off to Russia because ‘I felt that I ought to use all my spare time for something bigger.’ During the war he consoled Nowell that, if there were an invasion and the Germans were brutal to him, it would be because ‘we stand for something big and Eternal; and it is upon that which is Eternal and upon the Source of all that is big that we can confidently rely.’ Stalin, God and the Dean – that appeared to be the command structure of the Big Battalions, but not necessarily in that order.

For someone of Johnson’s temperament, to be made a dean was both ideal and fatal. It is no accident that all the most vicious feuds in Anglican life should centre on the deanery, as Trollope spotted and as was made manifest yet again in the row over the Occupy encampment at St Paul’s. A cathedral dean, once appointed, is virtually irremovable by either church or state, as Archbishop Fisher made clear to the House of Lords when backwoods peers staged a debate in the hope of getting rid of Johnson. Archbishop Lang had tried and failed; now Fisher, that flinty disciplinarian, offered Johnson the same deal: curb your public utterances or resign. Hewlett gaily rejected both options and sailed on, loathed by his canons, abhorred by the headmaster of the King’s School, Canterbury, John Shirley, who was as guilt-ridden as Johnson was nonchalant, and eventually by the pupils too, three hundred of whom signed a petition after Hungary, saying ‘We hope that this appeal to your strong humanitarian sense will shatter your misconceived faith in the Soviet Union.’ Some hope. The dean might be ‘blind, unreasonable and stupid’, as Fisher claimed, but nothing except extreme old age could shift him from his little kingdom. And nothing could shut him up.

What infuriated his critics, from Gollancz on the left to Fisher on the right, was that there was no evidence that Johnson had made any but the most superficial study of the issues that he spouted on with such mellifluous certainty, from famines in the 1930s to germ warfare in Korea. He believed everything his minders in Russia and China told him. It is hard to guess how much Marx or Lenin he had actually read.

Some reviewers found The Socialist Sixth so incredible that they wondered whether Johnson had actually written it himself. They were nearer the truth than they knew. Butler uses the archive to demonstrate that large parts of that book and of The Upsurge of China (1961) were copied, word for word, out of propaganda supplied by state organisations such as the Society of Cultural Relations with the USSR. The same is true of the memorial address he delivered to the British-Soviet Friendship Society after Stalin’s death, later published as a sixpenny pamphlet, Joseph Stalin, ‘by the Very Rev. Hewlett Johnson, Dean of Canterbury’. He had no pride of authorship and was as happy as any other Party hack to do anything for the cause. He didn’t have much interest in public debate: he orated, he didn’t argue. Tricky questioners were palmed off with a copy of The Socialist Sixth. His autobiography was entitled Searching for Light, but there was a good deal of humbug in the title, as there is in most titles couched in the participial optative. He had found the light first go, and what the light seemed mostly to illuminate was the persona of Dr Hewlett Johnson.

Butler expresses some puzzlement that both Stalin and Mao were so willing to grant the dean private but well-publicised audiences. Is this so mysterious? The dean was the prototype of the useful celebrity who could authenticate the benign intentions of the regime and, in particular, rebut accusations that it was persecuting the church. He was an unguent for internal as well as external application. The patriarch of Smolensk told him that The Socialist Sixth had been of such value to the church in Russia that he had given a copy to every priest in his diocese. The dean was all the more valuable because his office was so easily confused with the archbishop’s, which further enraged both Lang and Fisher.

In his last years, when he had become something of a joke, his usefulness to the Soviet bloc diminished and his prominence probably served only to blight the prospects for Christian socialism in Britain. Twenty years after his death, the members of the archbishop of Canterbury’s Commission on Urban Priority Areas were bewildered to find their report Faith in the City rubbished as ‘Marx in the City’ – a caricature of its mild and thoughtful critique. Johnson had never seemed interested in any varieties of socialism. For him, it was Communism and only Communism that had recovered ‘the essential form of the real belief in God which organised Christianity has so largely lost’. ‘While we’re waiting for God, Russia is doing it.’ There was no more to be said. It was futile for the canons of Canterbury to write to the Times in March 1940 dissociating themselves from the dean’s political utterances but insisting that they too believed it was the duty of all Christians to further social and economic reform. For Johnson, Stalin’s way was the only way. Instead of carrying on the milder tradition of F.D. Maurice and Charles Kingsley, of R.H. Tawney and Dick Sheppard (briefly his predecessor as dean), he obliterated the memory of it, just as Lenin and Stalin had obliterated the social democrats.

Besides, far from wishing to smooth over any little local difficulties, Hewlett exulted in them, though he pretended not to. He had every reason to oust the egregious Canon John Crum, who described him as ‘a slimy liar’ and boasted in a meeting of the chapter that ‘I always try all the time to pour ridicule and contempt over the dean.’ When the canon was finally forced out, Hewlett wrote to his wife: ‘CRUM IS GOING! How sad that I should have to rejoice but I do.’ More Heepishly, he wrote to Archbishop Temple: ‘My earnest prayer is that this good man’s sacrifice may be used by God to purge me if possible from faults which He alone sees.’ No question of anyone else being able to see any such faults.

Did he ever pause for a moment towards the end of his long life and wonder whether he might have been wrong about anything? Did he ever have another moment of doubt such as he had suffered in Professor Dawkins’s lecture room? In his summing up, Butler charitably offers the possibility that ‘perhaps the realisation finally dawned on him that he had reached a point at which he could no longer rethink his position without destroying himself and therefore had no option but to go on.’ Even that much self-knowledge sounds implausible. Hewlett Johnson was never much given to rethinking. Like many charismatics, he lived in an eternal present, a land of gestures without consequences, never looking back, always on the look-out for the next big thing. He would not have weakened at the last.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.