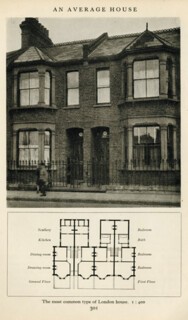

My wife and I arrived in England from New Zealand in 1960. Out of the window of the boat train from Southampton the backs of houses built in grimy stock brick were our introduction to London’s domestic architecture. We saw mile after mile of terraced houses, dating from the late 1800s and early 1900s. It must have been a couple of years later that I bought a copy of London the Unique City by Steen Eiler Rasmussen. First published in 1934, it gives a Dane’s take on the look of London, appreciative of both its architectural and its social history, and aware of its oddities. Even at the time Rasmussen’s view of English society must have seemed old-fashioned. But some things haven’t changed: ‘From railroads intersecting the suburbs of London,’ he wrote,

we see interminable rows of these swarthy little houses with all their protruding little kitchen wings. It is the most compact imaginable for a street house. The light in the rooms facing the yard is but spare, but the whole house is comparatively low. Also, as regards the front, the buildings from the end of the 19th century differ from those of the beginning. In order to use the narrow site each of these small houses has got a bay, and the brickwork is decorated with ornamented concrete details, columns, lintels and other trumpery. This typical house, built for people of the lower classes, contains two living rooms and kitchen on the ground floor and on the first floor three bedrooms and bathroom. These are the requirements of an average London house.

We bought just such a swarthy little house, backing on the railway, with its trumpery and a projecting kitchen wing, a couple of years after we got here. It was (and remains) adequate for our needs and we have lived in it ever since. Our daughter lives in a slightly smaller version built on the same pattern in Brixton and a couple of days ago we looked over the Brighton version our son and his partner have just bought. Today rising house prices have brought a wave of newcomers among us. They find themselves in a stratum of the available architectural genres that is, in various ways, not adequate to their needs.

One possible move, made famous in the 1960s by Alan Bennett’s String-Alongs, is to ‘knock through’, making a single large living room by joining an existing set of front and back rooms on the ground or first floor. As that cuts the actual number of rooms, excursions are then made into the loft with an anxious tape-measure to determine how many square feet of standing room can be won. ‘Not many’ is the usual answer. A more recent trick has been to incorporate the yard beside the kitchen extension into the extension itself, conjuring a big room (what a neighbour of ours called her ‘ballroom’) out of one or two smaller ones and a dingy backyard. The last possible direction to take was down. Town planners, always keen to preserve profiles and details, presumably worry less about new basements than new UPVC glazing bars.

It used to seem to me that terraced houses were infinitely adaptable. But after reading Rasmussen I came to believe that the changes from dwelling house to publishing house or lawyer’s chambers were no greater than the social and structural ones that came when a big house in Central London was turned first into flats and then bedsitters. It was then that I realised the size of the architect’s canvas mattered. Dividing up four or five floors presents problems and opportunities that do not arise when one of Rasmussen’s ‘typical houses’ is the starting point. When and how did bathrooms become regular features? Were the narrow ablution towers (tacked onto houses that look just old enough and odd enough) early evidence of a transition to a better washed, if chilly population. The bathroom in the first flat we rented at the end of Oxford Gardens, a couple of houses away from the Portobello Road, was half a floor down the common staircase. It was certainly the coldest bathroom I have ever lived with.

Changes to the interior usually took place without leaving any mark on the front façade; indeed it would seem that an attempt to date any townhouse built between the mid-1700s and the mid-1800s using only the architecture of the back view as evidence offers the untrained eye little to go on. The surviving buildings of that time, in versions of pure or fanciful Greek, Roman, Egyptian and Oriental styles, are more likely than not to have been broken up into flats, or become offices, hotels, museums or university buildings. The plasterwork in a grand building may have been preserved, but has to fight it out with smart new office desks. Smaller domestic interiors may preserve an undatable ceiling rose or clumsy chimneypiece, things covered in the estate agent’s prospectus by the phrase ‘many original features’. When panelled doors had not been replaced in the 1960s with modern flat ones, a new owner would sometimes find that a sheet of plywood was all that stood between the taste of 1960s DIY and the panelling chosen by an Edwardian spec builder.

One does get curious about how people lived. The musical taste of present neighbours may get on your nerves – noise is the worst sort of pollution – and piano practice grates too. (The one person I know who has taken the downward path and had a cellar excavated wants it for his band to work in.) When, I ask myself, did the last parlourmaid work in the streets around our house? The old lady who lived next door to us said that Lady Kingscliffe (there is a Kingscliffe Gardens in the neighbourhood) had a parlourmaid who had morning and afternoon uniforms. Did our own terraced house have such a grand retainer? The only evidence of social separation is the outside lavatory at the end of the kitchen extension. But were there live-in staff? I doubt it.

Harold Gilman’s Interior with Mrs Mounter was painted at the end of his life – he died in the flu epidemic of 1919. The subject – his rooms at 47 Maple Street and Mrs Mounter, his landlady – is evidence of how things changed in the 120 or so years between the work of the builder and that of the painter. One guesses the age of the house from the proportion of the windows and narrow glazing bars. The doors, the single one on the left leading to a landing and the pair on the right joining a front and a back room, indicate that the street windows are behind you. Just what floor you are on is not clear; it could be the first, second or third. The house has suffered a social decline in being divided into flats or bedsitters. The gaudy blue wallpaper could perhaps be traced in a catalogue from Maples, Heal’s or Sanderson.

London west of Tottenham Court Road has some well-preserved squares, but nothing to match those parts of Notting Hill that have become so civilised that the work of those who broke terraced houses down into multiple units has in many streets been flipped back. Much has changed since we had our first view of London terraces. Cars have driven children off the streets. The smoke has gone: was it a pain or a privilege to have felt our way through the last London Particular? Too many gardens have become parking lots and too many of the gardens that remain are spread with slate flakes. Houses have become absurdly expensive for those whose need is greatest.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.