In early March, while staying at our holiday cottage in Trafalgar on the KwaZulu-Natal south coast, I went swimming, as has been my habit for many years, in the idyllic Mpenjati lagoon. The lagoon looks pretty much the way it did when Vasco da Gama first saw it; the lower south coast and Trafalgar in particular are unspoiled – we frequently get duikers as well as monkeys in our garden.

As I neared the shore I hit my foot painfully on a submerged rock; a quick inspection showed that several toes were bleeding. I waded ashore, got home quickly and showered. The bleeding soon stopped but the next day my whole foot was sore. I tried to ignore it but matters rapidly got worse and soon I was running a fever and felt so ill I was giddy and unsteady on my feet. Eventually I decided I had to see a doctor, but things were so bad that I fell repeatedly while trying to get to the car and had to half-crawl across the garage to get in. How I managed to drive the 12 kilometres to Port Edward remains a mystery – I was lurching all over the road. Arriving at the offices of Dr Chetty, whose board advertises him as a dokotela (Zulu for ‘doctor’) trained in Mysore, I found several other patients ahead of me but stumbled over to the receptionist’s desk and explained that I was seriously ill.

Dr Chetty was wonderful. He immediately laid me on a table, gave me a drip, and in no time at all an ambulance had been arranged to take me to Margate Hospital. It turned out later – a great stroke of luck – that Dr Chetty had once before seen a patient suffering from what I had: necrotising fasciitis, caused by flesh-eating bacteria which rapidly invade and poison the body (the other man had died, as is normal with this disease). Almost certainly the reason the lagoon was polluted with such a deadly organism was to do with the dumping of raw sewage by communities living upriver.

Only months later was I able to Google necrotising fasciitis and find a long list of famous people who died from the disease, usually within 24 or 48 hours of contracting it. The medics at Margate muttered something about amputation but I was too far gone to say more than ‘whatever it takes.’ My conscious memory stops there – I was too ill and too sedated to participate in the drama that followed.

My wife, Irina, was teaching at Moscow’s new School of Economics when she heard the news and straight away flew back to Durban. She rang Margate from the airport and asked whether I was still alive. ‘He is critical,’ they said. She explained that it would take her 90 minutes to drive to the hospital: would I still be alive then? ‘He may – or may not be. He’s very, very critical.’ They had amputated the toes on my left foot and then, when the leg continued to swell, amputated my leg at the knee. But the poison had already invaded other parts of my body and all my systems – kidneys, lungs, heart etc – began to switch off. Multiple organ failure: that is, I began to die – that’s what dying is. I came close to fulfilling one of Woody Allen’s ambitions: ‘I don’t mind dying,’ he once said, ‘I just don’t want to be there when it happens.’

My blood pressure kept shrinking to levels where it was thought I must die at any moment. To counter the septicaemia I was shot full of antibiotics and to prevent my blood pressure falling too far I was given adrenalin. When Irina arrived my chances of survival were less than 30 per cent. I rallied twice, only for crises to follow each time. My brother and children flew in and there were anguished discussions about where I should be buried.

My surgeon, Dr Otto, and his colleagues at Margate undoubtedly saved my life. Yet I needed not only a ventilator and a dialysis machine, but also a hyperbaric chamber, which Margate didn’t have, so Irina decided to move me to St Augustine’s Hospital in Durban. I deteriorated further, and my left leg was amputated above the knee. To make things worse, the overdose of adrenalin, though it had saved my heart, had badly damaged the fingers of both hands – on my left hand three fingertips are blackened with dry gangrene and have lost all feeling – and the toes of my right foot. I also had bedsores on my head and bottom. Doctor friends warned Irina not to get her hopes up – the odds against my survival were still daunting.

I drifted in and out of consciousness a number of times but my first memory is of waking up in St Augustine’s intensive care unit in the first week of April with tubes controlling all my functions, unable to talk, and learning for the first time that I was missing a leg. Irina tells me that when it was explained to me that my leg had gone, I cried, but I have no memory of that. The regular morphine injections gave me the most terrifying and sophisticated nightmares I have ever experienced. Irina, my daughter and brother were all there and I communicated by tracing a spidery scrawl on a pad – my muscles had atrophied so much that I lacked the strength to write a sentence or lift an arm over my head.

Irina was at my bedside all hours of the day and night. I could never have recovered without her. Gradually things got a little better and some of the tubes came out, and then, one wonderful day, the dialysis was over. Better still, I moved out of the ICU – but then had to return because of persistent nausea and vomiting. Happily, this didn’t last long. I began to do more and more physio and exercise to rebuild my muscles; I followed the news and was able to learn about the progress of the book I had just published. Despite or possibly because of my complete inability to do any of the usual promotional work, the book was selling well and there were many nice reviews. That made a real difference.

After two more months in hospital I was basically evicted by my insurance company, Discovery Health, which refused to continue to pay for me to be there, though I was far from ready to leave. It was a gloomy business realising how threadbare my care policy was, as huge medical bills poured in of which they paid only a fraction. Discovery wanted me to go to a ‘step-down facility’ (which no one at the hospital had ever heard of) in a high-crime area. We decided that if we were thrown out it would be better to go back to the beach cottage at Trafalgar and take our chances.

In the meantime it was sobering to read of the ANC’s proposed new National Health Insurance scheme, which would forcibly conflate the public and private health sectors. Under ANC management the public sector has deteriorated very nearly to the point of collapse, with incompetent political placemen appointed as hospital managers, shortages of everything and, often, appallingly high mortality rates – all of it aggravated by a tidal wave of Aids victims that has pushed most other things aside. Doctors’ organisations have warned that the NHI scheme would be unworkable, that it would end access to First World healthcare for everybody and would lead to a huge new emigration of medical personnel. I am hardly an unqualified fan of the way private health works here, but I need no reminding that without access to First World hospital care I would have died. Should the NHI plan go ahead not only would most doctors emigrate but so too would many of the seven million South Africans of all races who currently depend on private health insurance as patients. What would be left of the economy if these seven million go is a subject worthy of a morphine nightmare.

So now I’m back at Trafalgar, paying for a private nurse and physio, exercising like crazy and getting steadily stronger. Some people make nice remarks about my positive attitude but actually I owe everything to Irina. For the rest I feel like Theseus, sent to fight the Minotaur in the labyrinth. That is, I’m in an intolerable situation and the only way out – learning how to walk with a prosthesis, to drive and be self-sufficient again – is to keep a tight hold on Ariadne’s thread and follow where it leads. That means working meticulously at the physio and teaching myself to do things like type this article with my gangrenous fingers.

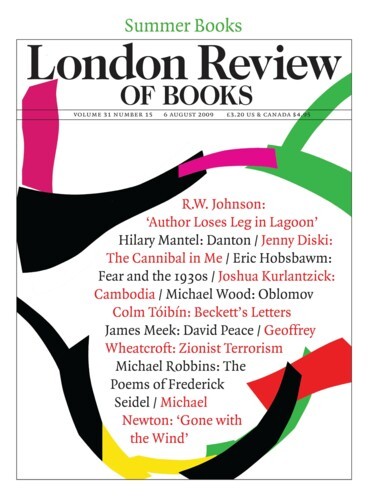

I look out from my bed at the Indian Ocean, which is the purest blue and pullulates with whale spouts, dolphins and the approaching signs of the annual sardine run, when shoals 30 or 40 kilometres long, billions upon billions of fish, move up the coast, allowing every imaginable predator a feast day. Everyone celebrates the sardine run as a sort of popular carnival, but of course like so many great natural events it’s built on the deaths of millions of creatures. Sometimes, as I gaze at the sea, I think about dying and how I nearly managed it, several times over. It seems incongruous given the gorgeous sunshine, the surf and the tropical vegetation – until you realise that it was in exactly these conditions that I cut my foot in the first place. I survived by a fluke; there’s no merit to it, though doctor friends try to make me feel good by telling me how strong I am and what a fight I put up. ‘Author Loses Leg in Lagoon’: my children saved the newspaper hoarding for me, its sheer banality a warning too. But mainly as I look at the waves I feel, ‘so far, so good.’ I spend no time at all regretting my left leg. It’s just so good to be alive.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.