The outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada, following Ariel Sharon’s provocative visit to the holy Muslim shrine on 28 September last year, reopened the question of whether the Oslo Accord is capable of producing a viable settlement of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians. Ever since it was signed on 13 September 1993 on the White House lawn and sealed with Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat’s hesitant handshake, the Accord has been a subject of controversy.

The following month the London Review of Books ran two articles about the Accord, one against and one in favour. Putting the case against, Edward Said called the agreement ‘an instrument of Palestinian surrender, a Palestinian Versailles’ and argued that, in signing it, Arafat had cancelled the PLO Charter, set aside all relevant UN resolutions except 242 and 338, and compromised the fundamental national rights of the Palestinian people. The document could not advance Palestinian self-determination, Said maintained, because self-determination entails freedom, sovereignty and equality.

In my article I put the case for the Accord. It was obvious that the document fell a long way short of the Palestinian aspiration to full independence and statehood. On the other hand, it was not presented as a full-blown peace treaty but, much more modestly, as a Declaration of Principles for Palestinian self-government, which would come into operation initially only in Gaza and Jericho. Despite all the limitations and ambiguities, I argued, the Accord represented a major breakthrough in the long and bitter conflict over Palestine. What mattered was that the two parties recognised each other, accepted the principle of partition, and agreed to proceed in stages towards a final settlement. I believed that the Accord would set in motion a gradual but irreversible process of Israeli withdrawal from the Occupied Territories and that it would lead, after the five-year transition period, to an independent Palestinian state over most of the West Bank and Gaza.

Over the last seven years, my mind has often gone back to this early debate. Who had the right reading, Edward Said or I? Sometimes I felt that the argument was going my way; at other times I thought it was moving his way. Zhou En-lai’s famous remark about the impact of the French Revolution, that it was too early to tell, might be said of the impact of the Oslo Accord. Said called his most recent book The End of the Peace Process: that strikes me as premature. What was started at Oslo is still alive, if only just. The peace process has broken down not because the Accord is inherently unworkable but because Israel has reneged on its side of the bargain.

The Oslo Accord did not promise an independent Palestinian state at the end of the transition period. It left all the options open. Similarly, nothing was said about the issues at the heart of the dispute, such as Jerusalem, settlements, borders and refugees. All these issues were deferred for the final-status negotiations scheduled to take place in the last two years of the transition period. The deal between Israel and the PLO was a gamble and Rabin knew this better than anyone. His body language at the signing ceremony revealed what he told his aides in so many words: that he had butterflies in his stomach. The prospect of an independent Palestinian state did not frighten him, so much as the momentous nature of the occasion. Provided Israel’s security was safeguarded, he was ready to go forward in the peace partnership with his former enemy, as he did when he concluded the Oslo II agreement on 28 September 1995. But five weeks later he was assassinated. The Oslo process had suffered its first serious setback.

The second major setback was Binyamin Netanyahu’s victory against Shimon Peres in the elections of May 1996. Netanyahu was a sworn enemy of the Oslo Accords, viewing them as incompatible both with Israel’s security and with its historic right to the Biblical homeland. But he knew that two thirds of the Israeli public supported the Accords and the policy of controlled withdrawal from the Occupied Territories that they had set in motion. Ever the opportunist, he began to trim his sails to the prevailing wind of public opinion, promising to respect Israel’s international obligations. Once elected, however, Netanyahu proceeded in his maddeningly myopic and transparently dishonest way to evade Israel’s obligations and to destroy the foundations that his Labour predecessors had laid for peace with the Palestinians. He kept talking about reciprocity while acting unilaterally in demolishing Arab houses, opening a tunnel in the Old City of Jerusalem, imposing curfews, confiscating Arab land and building new Jewish settlements on the West Bank. Under intense American pressure, Netanyahu signed the Wye River Memorandum in October 1998, promising to turn over another 11 per cent of the West Bank to the Palestinian Authority. True to form, he reneged on this agreement. Ironically, it was not the opposition that brought down his Government but his own nationalist and religious coalition partners who considered that he had gone soft on the Palestinians and that he had compromised the integrity of the historic homeland.

In the direct prime ministerial election held on 17 May 1999, Ehud Barak won 56 per cent of the votes to Netanyahu’s 44 – a landslide victory by Israeli standards, and a clear mandate to resume the struggle for a comprehensive peace between Israel and its neighbours. There was a strong sense that he was the right man in the right place at the right time. I was one of many Israelis who pinned their hopes on the new leader. In the epilogue to my book The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World, I wrote that Barak’s election was more than a political earthquake: ‘It was the sunrise after the three dark and terrible years during which Israel had been led by the unreconstructed proponents of the iron wall.’ In the LRB, on 16 September 1999, I went over the top again with an article on ‘The Propitious Rise of Israel’s Little Napoleon’. Mea maxima culpa.

What I failed to see at the time was that General Barak was simply the latest proponent of the strategy of the iron wall that had guided the Zionist movement from the earliest stages of the struggle for Palestine. The crux of this strategy – promulgated in 1923 by Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the founder of Revisionist Zionism – was that the Arabs could only be dealt with from a position of unassailable strength. Once Israel was sufficiently secure, a satisfactory settlement with the Palestinians and its other Arab neighbours could be negotiated. Menachem Begin, the leader of the Likud and a disciple of Jabotinsky’s, took the first step of the second stage by concluding a peace treaty with Egypt in 1979. Rabin, the leader of the Labour Party, took the second, highly significant step by negotiating the Oslo Accord with the PLO. Netanyahu took Israel back to the first stage of the strategy of the iron wall, that of shunning compromise and relying on force rather than diplomacy in dealing with the Arabs.

During the election campaign Barak presented himself as Rabin’s disciple, a soldier who later in life turned to peacemaking, and promised to follow his mentor down the Oslo path. Most observers, myself included, took him at his word. The real question was whether, as Israel’s most decorated soldier, he would be as successful at making peace with the Arabs as he had been at killing them. His record as Prime Minister shows clearly that he was not. He may have donned civilian clothes, but he has remained essentially a soldier. He is what in Hebrew is known as a bitkhonist – a security-ist. All developments in the region, including the peace process, are considered from the narrow perspective of Israel’s security needs and these needs are absurdly inflated – not to say, insatiable. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that Barak approaches diplomacy as if it were an extension of war by other means.

The new Prime Minister’s preoccupation with military power underlay his long interview with Ha’aretz (18 June 1999), in which he made a case for trying to reach an agreement with Syria first, on the grounds that it was a serious military power whereas the Palestinians were not. ‘The Palestinians are the source of legitimacy for the continuation of the conflict,’ he said, ‘but they are the weakest of all our adversaries. As a military power they are derisory.’ So there we have it: the Palestinians had no military power and posed no threat to Israel’s security, so they could safely be relegated to the back burner. What Barak implied was that a deal with Syria would leave the Palestinians weak and isolated and therefore more likely to accept whatever terms Israel offered them by way of a final settlement. During the first eight months of his Premiership, Barak concentrated almost exclusively on the Syrian track, but his efforts ended in failure.

The Palestinian track could not be avoided altogether, not least because of the written commitments entered into by Barak’s predecessors. His own reservations about the Accords were widely known. As Chief of Staff in 1993 he was not informed about the secret negotiations with the PLO in the Norwegian capital, and he was highly critical of the Accord that was reached there. In 1995 he was Minister of the Interior and abstained in the Cabinet vote on Oslo II. His main objection to the Oslo process was that it put the onus on Israel to divest itself in stages of its territorial assets without necessarily leading to a definitive resolution of the conflict with the Palestinians. This was a curious objection because gradualism and the principle of land for peace lay at the heart of Oslo. Interestingly, Barak’s first offer to Arafat was to skip the small redeployments stipulated in the Wye River Memorandum and go for the big bargain. But Arafat insisted that all previous commitments had to be fulfilled before proceeding to the final-status negotiations.

In the subsequent negotiations Barak put intense pressure on the Palestinians. His diplomatic method could be described as peace by ultimatum. The outcome was an agreement signed at Sharm-el-Sheikh on 4 September 1999. The new accord – known as Wye II – allowed more time to carry out the redeployments agreed to at Wye and put in place a new timetable for the final-status talks. Israel and the Palestinian Authority agreed to make a ‘determined effort’ to reach a ‘framework agreement’ on the final-status issues by February and to sign a fully-fledged peace treaty by September 2000. Like all previous Israeli-Palestinian agreements, Wye II reflected the balance of power between the two parties. Israel exploited its strong bargaining position in negotiating successive agreements but also modified the agreements after they had been reached. Netanyahu had had reservations about the Oslo Accords, so he refashioned them in his own image and the result was the Wye River Memorandum. Barak had reservations about this Memorandum, so he refashioned it in his own image and the result was Wye II. How did the Palestinians figure in all this? The implicit answer is that beggars cannot be choosers.

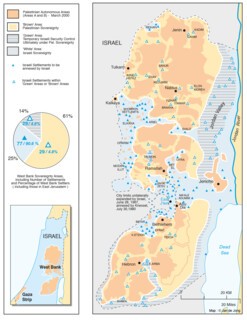

All the deadlines written into the Sharm agreement fell by the wayside. Barak seemed intent on giving an illusion of progress while avoiding making any substantial moves. He repeatedly stated that Israel would do everything in its power to reach a settlement. But his words sounded rather hollow against the backdrop of persistent Israeli violations of the Oslo Accords. The third Wye redeployment was not implemented. Arab villages around Jerusalem were not turned over to the Palestinian Authority as previously promised. The safe passage between Gaza and the West Bank was not opened. Palestinian prisoners held in Israeli jails were not released. Worst of all, the old Zionist policy of creating facts on the ground went forward at full speed. More Arab land was confiscated on the West Bank, new hilltop settlements were established, existing settlements were expanded and many more roads were built for the exclusive use of the Jewish settlers. True, the Oslo Accord did not explicitly prohibit settlement activity. True, some settlement activity had gone on under all three previous Prime Ministers. But under Barak the building of settlements proceeded at a frenetic pace and in blatant disregard for the spirit of Oslo. Barak seemed intent on tightening Israel’s control over the Palestinian territories. The idea of coexistence based on equality was utterly alien to his way of thinking.

One of the clearest illustrations of Barak’s belief that he could impose his own terms on the Palestinians was the summit held at Camp David in Maryland in July last year. The request for the summit came from Barak – and Bill Clinton, ‘the last Zionist’ as one Israeli newspaper aptly called him, obliged. At the summit Barak presented a package which covered all the key final-status issues, including a proposal for the division of East Jerusalem. His spokesmen proclaimed that he had gone further in meeting Palestinian demands on Jerusalem than any other Israeli Prime Minister. This was true but it did not mean much since all previous Prime Ministers had dodged the question. All Israeli leaders since 1967, Labour as well as Likud, routinely repeated the slogan that a united Jerusalem is the eternal capital of the state of Israel. What the official spokesmen omitted to mention was that in return for the modest concessions on offer, their leader had insisted that the Palestinian Authority renounce any further claim against the state of Israel, including the right of return of the Palestinian refugees. Barak’s great mistake was to insist that Arafat make an unequivocal statement about ending the conflict because even if he had signed such a declaration, it would not have ended the conflict. As it was, he was under strong pressure from his own people and from the leaders of some of the Arab states, notably Egypt and Saudi Arabia, not to sign. He was reminded that the entire Muslim world has a stake in Jerusalem, not just the Palestinians. In the end, after two weeks of talks, he rejected the package and returned home to a hero’s welcome.

The collapse of the Camp David summit fuelled Palestinian frustration and deepened the doubts that Israel would ever voluntarily accept a settlement that involved even a modicum of justice. The conviction gained hold that Israel only understands the language of force. And then, on 28 September, Ariel Sharon went on his much-publicised visit to the Haram al-Sharif. Barak had approved the visit against the advice of his security chiefs. Sharon himself claimed to be carrying a message of peace but, if so, why did he need a thousand security men to accompany him? Sharon is the most reviled man in the Arab world. His visit to the Muslim ‘Noble Sanctuary’ provoked angry reactions which quickly snowballed into a full-scale uprising – the al-Aqsa Intifada. The move from rocks to rifles on the Palestinian side and the resort to snipers, tanks, rockets and attack helicopters by the Israelis drove the death toll inexorably upwards. In the first three months of almost daily clashes, 298 Palestinians, 13 Israeli Arabs and 43 other Israelis were killed. The peace process ground to a standstill and many pronounced it dead.

Israel closed the borders of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, consigning 2.3 million people to an open-air prison. Some 110,000 Palestinians who work in Israel are idle. Unemployment rose to 40 per cent as a result of the blockade. The economic punishment meted out by the Israeli occupation forces has been savage. Acres of Palestinian olive groves and farmland have been bulldozed by the Israeli Army. The Palestinian economy lost more than £345 million in the first sixty days of the crisis. Three years of progress were wiped out in two months of conflict.

On the diplomatic front, however, the conflict worked against Israel and in favour of the Palestinians. The brutality with which Israel tried to put down the popular uprising drew widespread condemnation. In the twilight of his Presidency, Clinton launched a vigorous initiative to broker a final peace deal. In comparison with the American ‘bridging proposals’ tabled at Camp David, his peace plan shifted significantly in favour of the Palestinians on the issues of Jerusalem, the new state’s borders and the refugees. According to this plan, Israel would concede most of East Jerusalem (with the exception of the Jewish Quarter in the Old City and a corridor leading to it), and in return the Palestinians would give up the UN-supported right of return for the 3.7 million refugees. On top of that, the Palestinians would get a state of their own on 95 per cent of the land of the West Bank and the whole of the Gaza Strip.

Barak accepted Clinton’s plan as a basis for negotiations, probably on the assumption that Arafat would reject it, thereby giving him the propaganda victory. But Arafat confounded his calculations by accepting the American plan – in a heavily qualified version. Electoral considerations also pushed Barak to change tack and to start sounding much tougher and much more pessimistic about the prospects of a US-brokered deal. A prime ministerial election will take place on 6 February, and the opinion polls show Barak trailing Sharon by as many as 20 points. While Sharon, the hardliner, is trying to soften his image to woo votes from the centre, Barak has adopted a hawkish rhetoric in the hope of recapturing the middle ground. He said he would not go to Washington to discuss peace until the Palestinians ended the violence. He also warned that the uprising could turn into a full-scale regional confrontation and raised the prospect of Israel unilaterally annexing large chunks of the West Bank. Once again, as so often in the past, the peace process is held hostage to the vagaries of internal Israeli politics.

The Oslo Accords did not fail: it was Ehud Barak, following in his predecessor’s footsteps, who undermined them. The Accords are about identifying and cultivating common interests: Barak has all but destroyed the faith of the Palestinians in the possibility of co-operation and coexistence with Israel. What is at stake in this conflict is not Israel’s security, let alone its existence, but its 1967 colonial conquests. Under General Barak’s leadership the Israeli Army is waging a colonial war against the Palestinian people. Like all colonial wars it is savage, senseless and directed in the main against the long-suffering civilian population. Small wonder that a growing number of IDF recruits and reservists are refusing to serve in the Occupied Territories.

Palestinian disenchantment with the so-called peace process is much more widespread and it goes much deeper. When the Palestinians embarked on this process in 1993 they made a strategic choice: they assumed that they could advance towards a state of their own only by diplomacy and not by violence. Now they are not so sure. The al-Aqsa Intifada seems to show that to make any impression on the Israel of General Barak, diplomacy must be backed by violence and the threat of violence. In other words, the Palestinians have learned from bitter experience that the only language Israel understands is the language of force. Arafat has been calling for the peace of the brave ever since the first Oslo Accord was signed. Seven years on, he is confronted by an opponent who seems determined to impose the peace of the bully. But, in the long run, bullying cannot solve the Palestinian problem. The only sure way to end the conflict is by ending the occupation. What is more, by ending the occupation Israel would be doing itself a great favour. As Marx pointed out a long time ago, a nation that oppresses another cannot itself remain free.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.