Just one more species doing its best

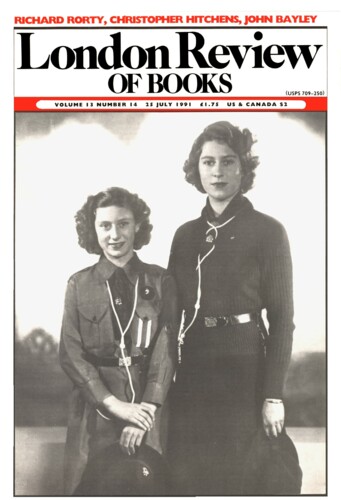

Richard Rorty, 25 July 1991

A.J. Ayer began his Bertrand Russell with his customary insouciance, saying that Russell was ‘unique among the philosophers of this century in combining the study of the specialised problems of philosophy, not only with an interest in both the natural and the social sciences, but with an engagement in primary as well as higher education, and an active participation in politics’. Dozens of 20th-century philosophers have, I imagine, met those specifications. But the one who comes first to an American’s mind is John Dewey: a man whose engagement in primary and higher education, and whose active participation in politics, were considerably more extensive than Russell’s – and, I should argue, more focused, intelligent and useful.’