Marilyn Butler

Marilyn Butler, who died in 2014, was King Edward VII Professor of English Literature at Cambridge and rector of Exeter College, Oxford, the first woman to head what had been a men’s college. Her books include Jane Austen and the War of Ideas and Romantics, Rebels and Reactionaries: English Literature and Its Background, 1760-1830 as well as a biography of Maria Edgeworth, whose works she also edited.

No Fear of Fanny

Marilyn Butler, 20 November 1980

Erica Jong’s Fanny has had a long gestation. In 1961, as an undergraduate, she was taught by the late Professor James L. Clifford, Johnson’s biographer, who had the admirable policy of inviting his class to imitate an 18th-century author instead of writing yet another academic paper on him. At the time, Ms Jong came up with a mock epic in heroic couplets in the manner of Pope, and a novella in the style of Henry Fielding. After several volumes of poetry and a runaway success with her bawdy modern picaresque, Fear of Flying, she still likes the challenge of the Clifford assignment. Fanny, being the True History of the Adventures of Fanny Hackabout-Jones, is a quaint and belated substitute for the Columbia doctorate on 18th-century literature which Ms Jong abandoned in the mid-1960s.

Reviewers

Marilyn Butler, 22 January 1981

The short topical review-article is a literary discovery of the last two hundred years or so – the age of mass literacy and the mass-circulation newspaper. A good review column is read by more people than any criticism at book length, and often deserves to be. It should have been the review and not the novel that Jane Austen meant when she hailed the form in which ‘the liveliest effusions of wit and humour are conveyed to the world in the best chosen language.’ She might also have had reviewers in mind, not novelists, when she noted their extraordinary sheepishness in alluding to their own skills. Some of the very best are nowadays competing with one another in that ungenerous and impolitic custom ‘of degrading by their contemptuous censure the very performances, to the number of which they are themselves adding’.

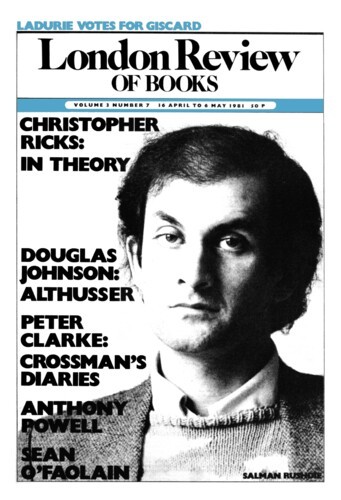

Action and Suffering

Marilyn Butler, 16 April 1981

Why is the novel frightened of ideas? When did the dominant literary form of Western society turn away from dealing with large issues? Mary McCarthy’s 1980 Northcliffe Lectures begin by asking such questions with verve and elegance. Perhaps, she thinks, it is all the fault of the old maestro Henry James. As a critic, and even more as a practitioner, he got the public used to the doctrine of the novel as fine art, ‘a creation beyond paraphrase or reduction’. In James’s novels, the characters are typically made to talk of one another, and not of the issues that in real life are exercising the author’s fellow citizens. ‘What were Adam Verver’s views on the great Free Trade debate, on woman suffrage, on child labour? We do not know.’ But if the number of concepts allowed into James’s fiction is drastically restricted, compared with the ideas that are kicked around in, say, Little Dorrit or Middlemarch, so too are the specific things. What are the ‘spoils of Poynton’, the exquisite treasures for which Mrs Gereth and Fleda Vetch care so much? Furniture? Objets d’art? Have they the consistency of a collection, or are they heterogeneous treasures, linked only by their beauty and by their commercial value? The hints James gives are scarce and confusing. ‘It was a resolve, very American, to scrape his sacred texts clean of the material factor … He etherealised the novel beyond its wildest dreams.’

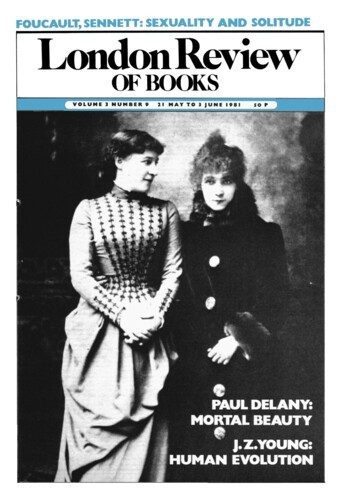

Jane Austen’s Latest

Marilyn Butler, 21 May 1981

‘There would be more genuine rejoicing at the discovery of a complete new novel by Jane Austen than any other literary discovery, short of a new play by Shakespeare, that one can imagine.’ Brian Southam begins his Introduction to ‘Grandison’ by quoting the apparently prophetic observation of Margaret Drabble in 1974. Ever since she said it, there has been a run of near misses or all-buts, beginning with Another Lady’s completion of Jane Austen’s fragment ‘Sanditon’, and continuing with someone else’s notion of ‘The Watsons’. Then, in the autumn of 1977, there was an Austen discovery, not of a novel but not of a fragment either – a complete new play, apparently Jane Austen’s version of a work she had admired from childhood, Samuel Richardson’s Sir Charles Grandison.

Pieces about Marilyn Butler in the LRB

Talk about doing

Frank Kermode, 26 October 1989

Anyone presuming to review works of modern literary theory must expect to be depressed by an encounter with large quantities of deformed prose. The great ones began it, and aspiring theorists...

The Sage of Polygon Road

Claire Tomalin, 28 September 1989

Mary who? was the person I mostly seemed to be dealing with in the early Seventies, when I wrote a biography of the extraordinary woman whose works have now been collected for the first time,...

Fiery Participles

D.A.N. Jones, 6 September 1984

Hazlitt is sometimes rather like Walt Whitman, democratic, containing multitudes, yet happy with solitary self-communion. In a pleasant essay called ‘A Sun-Bath – Nakedness’,...

Citizens

Christopher Ricks, 19 November 1981

‘Authors are not the solitaries of the Romantic myth, but citizens.’ The spirit of Marilyn Butler’s excellent book on the Romantics is itself that of citizenship: of belonging...

The Case for Negative Thinking

V.S. Pritchett, 20 March 1980

One of the pleasures of reading Peacock in the Thirties, when I first read him, was that he was without acrimony. He enabled us to relive the great battles of ideas in the 19th century without an...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.