Lawrence Hogben

Lawrence Hogben was the first Royal Naval Instructor Officer ever to win a DSC. Subsequently, his forecasts helped persuade Eisenhower to postpone D-Day from the stormy 5 June to the more clement 6 June (an episode he recounted in the LRB in 1994).

Getting on the reader’s wick

18 December 1986

Planetary Sparks

19 December 1991

Der Tag

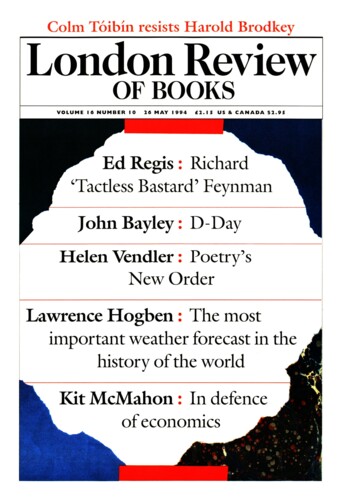

26 May 1994

Diary: The Most Important Weather Forecast in the History of the World

Lawrence Hogben, 26 May 1994

‘Everything on the Normandy beachhead will hang on your weather,’ said the D-Day planners, assuming that we meteorologists had total control of the elements. ‘Just name us five fine, calm days and we’ll go.’ A hundred years of weather records suggested there was no hope of their getting this. They limited their demand to ‘a quiet day with not more than moderate winds and seas and not too much cloud for the airmen, to be followed by three more quiet days.’ On top of this, the military insisted on a late full moon for the parachutists, plus a tide that would be high three hours after pioneer forces had landed at dawn to clear paths through the beach mines and other obstacles. Tides and moon being fully predictable, they would determine possible dates. July would be too late, and May too early. That left just four possible days: 5, 6, 19 or 20 June. We worked out the odds on the weather on any one of these four dates conforming to requirements as being 13 to one against. So meteorologically, D-Day was bound to be a gamble against the odds.

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.