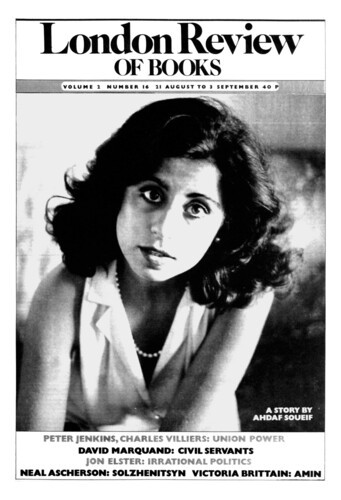

Cityscape with Figures

Julian Symons, 21 August 1980

How does a novelist write about World War Two or the war in Vietnam? About populations deliberately enslaved or exterminated, destruction seen as normal? American writers differ from British novelists in approaching such all-embracing violence as too grotesque to be viewed in any terms except those of fantasy. There are no British novels that, like Catch 22, approach war as lunacy made real, or implicitly ask, like Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers, why running dope is worse than killing unarmed Vietnamese. Such a mixture of the macabre and the grotesque with a touch of anarchy is not a British vein. There are extraordinary figures in Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy, some of them, like Apthorpe, pushed to the edge of caricature: but although the people may be comic, the war itself is a serious matter. There is something dotty about Ritchie-Hook, the defence of Crete is a shambles, but in the end Waugh’s work belongs within the realistic tradition of the English novel. So does Olivia Manning’s Balkan trilogy, which is the only other lengthy attempt by an English novelist to handle part of World War Two as a theme. (Anthony Powell’s three relevant volumes in The Music of Time are too closely woven into the rest of the series to be considered.)