Living Things

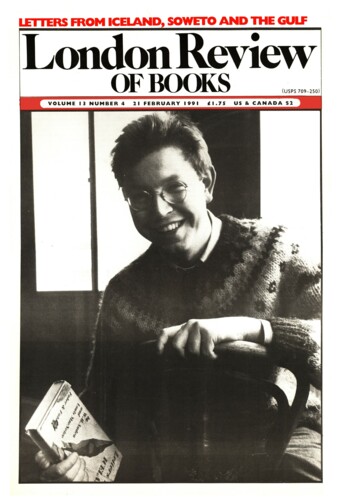

Ian Hacking, 21 February 1991

‘War,’ said an old peacenik poster with the words scrawled across a child’s drawing of a tree, ‘is harmful to children and other living things.’ This subtle and sophisticated book has a little of that same power to shock by innocence. It is about how children think of living things, less a matter of what they learn than of what human nature teaches about nature. That is a pleasing picture but not a popular one. Atran is not in search of opponents, but here are a few of the things he is up against … Every people classifies in its own ways: it is cultural imperialism to expect our sortings of life to be duplicated by others (standard all-purpose cultural relativism). Aristotle was a disaster for biology: he taught that plants and animals should be defined by a priori essences that not only devalued observation but also made it impossible to attend to variations among the species, thereby impeding evolutionary thought for two millennia (textbook history of biology). The taxonomies of natural history are an artwork of the Enlightenment; the Renaissance was mired in a wonderful world of resemblance, natural magic and the doctrine of signatures, whereby plants were the signs of minerals which were the signs of stars (François Jacob, Michel Foucault). The semantics of natural kind terms is such that, when we speak of living things, we are referring, whether we know it or not, to the fundamental kinds at which science aims (Saul Kripke and, sometimes, Hilary Putnam). We have an obligation to integrate our commonsense categories into the best knowledge available; when there is conflict, common sense yields to knowledge (most good scientists, starting with Aristotle).