The Plot to Make Us Stupid

David Runciman, 22 February 1996

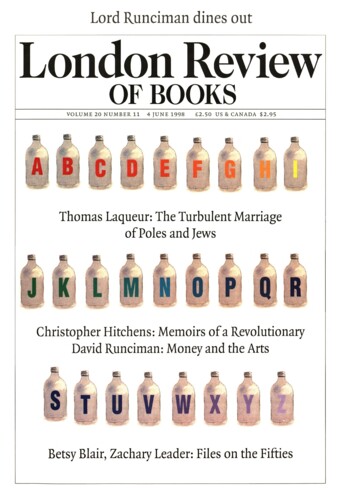

‘Why is it,’ asks the mathematician John Allen Paulos in his book about the pitfalls of innumeracy, ‘that a lottery ticket with the numbers 2 13 17 20 29 36 is for most people far preferable to one with the numbers 1 2 3 4 5 6?’ It is not an easy question to answer. All lotteries, after all, rely on a recognition by those who participate in them that the winning numbers are chosen at random, if only so that the participants can feel that their numbers have as good a chance of coming up as any others. People need to know it is random, because random translates as ‘fair’. However, all lotteries also rely on their participants having a sense that some sequences of numbers are more likely to come up than others. Once it is seen that all sequences have precisely the same chance of coming up as 1 2 3 4 5 6, the whole business of participation starts to look a lot less attractive. So participants fall back on, and are encouraged to fall back on, a belief that random-looking sequences are more likely to be chosen at random than sequences that look familiar. This belief is a delusion, but it is a peculiarly powerful one – even a probability theorist would have to be feeling fairly tough-minded to select, as an example of six numbers chosen at random, the second of Paulos’s sequences in preference to the first.