What is reading?

Gill Partington

Behind the handsome 18th-century façade of The Hague’s Museum Meermanno, ‘the House of the Book’, pages are turning. Everywhere you look they are turning over, but also turning into other things: screens, data, moving image, sound, even skin. The Art of Reading: From William Kentridge to Wikipedia is not so much an exhibition of contemporary book artists as an attempt to use their work to ask what reading is. The question has increasingly exercised theorists and scholars as the printed book loses its dominance, but here the overfamiliar act is scrutinised through the lens of art.

A series of thematically arranged installations lead you to consider it from various angles: touching; seeing; remembering; concentrating; reacting. The cumulative effect makes reading sufficiently alien to leave you wondering how on earth you perform this weird feat. What does it mean to see written marks and transform them into meaning, or into speech? Does reading take place in the mind, the eye, the body, or in the digital devices on which we increasingly rely?

There is plenty of button pressing and screen swiping on offer, but this is no celebration of interactive gadgets or digital media’s ‘enhanced’ reading experience. Instead, there are thoughtful explorations of its blockages and complications, and the sensory and cognitive short circuits made manifest through 21st century technology. The theme is often unreadability: 56 Broken Kindle Screens by Sebastian Schmieg and Silvio Lorusso nicely illustrates the stand-off between analogue and digital. Images of glitched, cracked, illegible ebook screens are collected in a printed volume: a graveyard of digital reading consigned to the page.

In Rick Myers’s film An Excavation, A Reading, the letters of a poem, shaped out of powdered marble, are scattered by the sound waves of its own recitation. Speech and text cut across rather than complement one another.

A Dialogue in Useful Phrases by Elisabeth Tonnard is an exploration less of unreadability than of misreading, as the printed sentences in an antiquated phrasebook are transformed into a strangely charged to-and-fro between male and female voices. What you hear is different from what you read, even though the words are identical. The overall effect is often to confuse the senses, making us unsure whether to use our eyes, ears or hands.

The page is a blank surface activated by touch in Carina Hesper’s Like a Pearl in my Hand. Its thermochromatic ink responds to body heat, gradually revealing images of blind children ‘hidden’ in Chinese orphanages. We touch the page, and it touches us. Reading starts to seem less like a single act than an awkward composite of looking, listening and feeling.

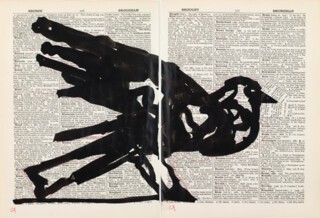

William Kentridge’s Second Hand Reading begins with the pages of a dictionary, doodling over each of them before transforming them into a hypnotic animated film. It’s an elaborate extended flipbook. You can physically leaf through the volume while watching the film do the same, but at a speed that stops you processing its text. The effect is oddly disorientating. Are you looking or reading? Where exactly does the work lie, on page or screen? And which of these is ‘second hand’? The film of the book, or the book of the film? The answer seems to be both.

The trick of The Art of Reading is to make you aware of the layers of technology, convention and artifice that intervene between you and the page. In one room you put on an OrCam Reader, not an art piece but spectacles designed for the sight-impaired, which use character recognition software to scan text. You look at a poem and a tiny speaker inside the glasses recites it for you, an automated voice reading over your shoulder.

Amaranth Borsuk and Brad Bouse’s Between Page and Screen is a disorientating experience, too, inviting us to hold an iPad’s webcam above the page of a book, so that a printed code triggers digitally animated text. On a screen in front of us we see both the flat surface of the page and the previously invisible letters that now rise from it, dancing and dissolving as it is turned. But who or what is doing the reading? You or the machine? It’s a show that leaves you with a disconcerting sense that reading is uncanny, constantly at one remove, and always second hand.

Comments

And wasn't my mind also like another crib in the depths of which I felt I remained ensconced, even in order to watch what was happening outside? When I saw an exterior object, my awareness that I was seeing it would remain between me and it, edging it with a thin spiritual border that prevented me from ever directly touching its substance; it would dissipate somehow before I could make contact with it, just as an incandescent body brought near a damp object never touches its wetness because it is always preceded by a zone of evaporation. In the sort of screen dappled with different states of mind which my consciousness would unfold at the same time that I was reading, and which ranged from aspirations hidden most deeply in myself to the completely exterior vision of the horizon that I had, at the bottom of the garden, before my eyes, what was first in me, innermost, the constantly moving handle that controlled the rest, was my belief in the philosophical richness and the beauty of the book I was reading, and my desire to appropriate them for myself, whatever that book might be.

The Way by Swann’s