The Ensor exhibition at the Royal Academy (until 29 January) is for me the event of the autumn. It is twenty years since Ensor had a show in London, and another sixty years before that since the Leicester Galleries’ retrospective of 1936 (the artist was still alive, but the handful of years round 1890 when most of his best work had been done must already have seemed remote). Luc Tuymans has chosen wonderfully for the present survey – thirty paintings, fifty merciless drawings and prints – and Antwerp and other Belgian collections have lent with touching generosity. I hope the Belgians will forgive me if I say that looking at Ensor in the Academy struck home as hard as it did partly because the paintings seemed to me to connect so deeply, and so variously, with the line of French art from Delacroix to Cézanne. This is the art from which Ensor drew his strength. I know he was fond of saying in his later years that ‘J’entends ignorer mes influences,’ and ‘Paris m’est totalement inconnue,’ but he did not expect anyone to believe him. His imagery was rooted in the traditions of the Low Countries, with Brueghel and Bosch constant companions; but as a painter – as a colourist, as a manipulator of impasto – Ensor spent his life dreaming of Delacroix and Monticelli and Moreau, and what the Impressionists had done, especially the high-speed Manet of the 1870s. I’m sure he must at some point have seen early Cézannes – The Orgy, perhaps, or Achille Emperaire, or a Temptation of St Anthony – and thought about repeating them in the key of late Turner. But Delacroix was always the presiding genius. The Fall of the Rebel Angels in the show is a wild précis of Delacroix’s Apollo ceiling (with Brueghel in the background). Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise draws from the same source. The great anarchist Entry of Christ into Brussels in 1889 – too big and fragile to travel to London, but represented by an unrepentant etching Ensor did of it six years later (only the blood-red banner reading ‘Vive la Sociale’ has been suppressed) – recasts Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People as an endless crowd of carnival Crusaders Entering Constantinople.

Perhaps it is true that an artist’s influences should not interest us much (Ensor’s wish to drop the subject has my sympathy) unless what they give rise to in the work before us is baffling, yet immediately coherent in its own right, and also an achievement that, once seen, appears to upend our view of the tradition being drawn on, putting that tradition in a new light. This is the Ensor effect. Who, without The Intrigue or Skeletons Fighting for the Body of a Hanged Man, would truly have grasped how much it mattered to French painting all through the 19th century – and still in the age of Picasso and de Chirico – that the ordinary, daily, material life of modernity be seen to be haunted by the unreal, the deathly, the disguised, the predatory, the phantasmagoric? The famous tagline Walter Benjamin borrowed from Leopardi – ‘Fashion: Madame Death! Madame Death!’ – seems made for the world Ensor shows.

Look again at The Intrigue and Skeletons Fighting. What seems to me stupendous about them (and thoroughly Boschian) is their ability to convince us that horror and absurdity are familiar events, behaviours we all recognise from our daily round. The colour and touch Ensor brings on to support that intuition do both hover, yes, on the edge of the showy. But in the years round 1890 that edge was where a renewed modern realism seemed possible. Garishness and matter-of-factness were faces of the same coin – never more painfully than in pictures like these. Which of the two concepts just tried on for size – garishness and everydayness – applies, for instance, to the charity-shop outfit of the figure on the left in Skeletons Fighting? Or the mouldy yellow fur of the man in The Intrigue? (His mask-face as frightened and disconsolate as a face in painting has ever been.) Or the ward-doctor whites belonging to the hanged man? (The ‘CIVET’ pinned to the corpse’s chest is presumably the kind Lear asked the apothecary for, ‘to sweeten my imagination’. The line of dried blood leading from tongue to placard is happily unreproducible.)

I concede that once I start describing a good Ensor I can’t stop piling on gory detail. But this is not what happens in front of the real thing: the pictures are not chambers of horrors. Their detail may regularly be disgusting or tawdry or delectable (almost in the way of Baudelaire’s ‘Une charogne’), but by and large it is firmly contained, almost neutralised, by the whole painted rectangle, that is, by the ordinariness of the masqueraders’ surroundings, and the sober underlying view of bourgeois society being proposed. What makes Skeletons Fighting so chilling, to put it another way, is the grim seedy decency of the picture’s colour: the force of its ice-cold blues, greens and whites, one of the blues entombing a skull staring up at us reproachfully from ground level; and above all the schoolroom joylessness of the picture’s floorboards and back wall. No theatre of cruelty has ever been provided with a less glamorous stage. Ensor’s whole sense of space in these 1890s pictures is unerring. The nastiness and pathos of his bourgeois undead – there is a picture (not in the show, though again a later etching is there as reminder) where the skeletons huddle for warmth round a woodstove, one of them clutching a painter’s maulstick and palette, another with a violin – would be infinitely more dismissible, put down as mere whimsy, if Ensor had not, in ways just described, so completely realised the bare rooms and bric-à-brac and dismal ‘hangings’ in which his maskers seek their thrills. In the third of the great 1890s paintings lent by Antwerp to the show, L’Etonnement du masque Wouse, the room is enlivened by an evanescent green and pink Oriental landscape, with birds of paradise and mystic lilies, the kind Ensor’s art-world particularly treasured. ‘Etonnement’ here – the title is Ensor’s, given when he first showed the painting in Brussels – is difficult to translate. The masqueraders are certainly not astonished by their own or anyone else’s behaviour – that’s part of Ensor’s point – just disoriented, maybe interested for a moment, then bored, resentful, smug, sneering, nihilistic. A critic in La Jeune Belgique in 1890 struck the right note: Ensor’s colours, he wrote, reach back essentially to Goya’s, and so does his view of life. ‘Il fait penser à cette lignée terrible et maudite: Maldoror, Rimbaud.’ He has given us a new set of Black Paintings reimagined by a cackling van Gogh.

And yet there is tenderness in Ensor – an unmistakable fellow feeling for his marionettes. He would be an immensely lesser artist (as would Goya and Rimbaud) if there were not. The Intrigue is drenched in pity – almost to its detriment, but not quite. Those who care about Ensor as an artist have always been fascinated by the length of time he lived on after his six or seven years of inspiration – he died in 1949. He became, I would say entirely knowingly and deliberately, a ghost or simulacrum of himself, more and more accepting the role of dead ornament to a regime his art had once savaged. Baron Ensor, eventually. But hadn’t his art always predicted such a future? Wasn’t one form or another of undeadness what Ensor believed – felt – bourgeois society had in store for all of us? Isn’t the intimacy of these paintings with desperation and aimlessness – with false vitality – what gives them enduring power?

Ensor is one of the strangest artists to have emerged from a socialist and anarchist milieu – stranger even than Platonov or Pasolini. That socialism of some sort was the context that mattered in his case is clear. The first serious piece of writing about him appeared in 1891 in the socialist journal La Société nouvelle, published in Paris and Brussels: it was written by a novelist friend, Eugène Demolder. When Demolder followed up with a short book a few months later it was titled James Ensor, la mort mystique d’un théologien. (The great Verhaeren, poet of the revolutionary crowd, lent his name to a second monograph in 1908.) You have to work hard to find Demolder’s 1892 subtitle acknowledged in the art-historical literature, but it is important, and only half ironical. In Belgian socialism at fin de siècle, Christ and La Sociale (the anarchists’ codeword for the coming social revolution) were inseparable. Demolder in La Société nouvelle has Ensor’s Christ ‘step down into the crowd and slap the ridiculous bishop with his stigmatised hands’. There is a ferocious Man of Sorrows in the show, painted the same year as Demolder’s essay, whose Christ seems fully capable of doing the job. He is best looked at in tandem with a panel hung nearby, also dated 1891, titled Skeletons Fighting over a Pickled Herring. No doubt the panel’s strip-cartoon pessimism is all-encompassing – ‘Father, forgive them for they know not what they do’ – but at the same time it resonates specifically with Ostend and class struggle. Ostend in the late 19th century (it was Ensor’s home, and he rarely stirred far from the place) shared its bathing beaches with a hard-scrabble fishing industry – it was Bognor with a large dash of Grimsby. In August 1887 fish packers set on three English boats trying to undersell the locals, and gendarmes shot dead six or more of the rioters, wounding scores of others (the numbers are disputed) before order returned. There is a drawing at the Academy called The Strike, but its first title seems to have been Le Massacre des pêcheurs ostendais. Notice that one of the skeletons in the Pickled Herring picture is sporting a busby. Ensor did a painting in 1892 of fishermen’s wives warming themselves over individual braziers shoved under their skirts, in a room as wintry and miserable as the room in Skeletons Fighting for the Body of a Hanged Man; naturally, skull people peer in through a window. One of them carries a heartless placard: ‘A Mort! – Elles ont mangé trop de poisson.’

The sensibility – the precise strain of anarchistic socialism – that issues from this pattern of sympathies has always been hard to pin down. Demolder’s subtitle speaks to that. Looking again at The Intrigue or L’Etonnement du masque Wouse, I find Ensor’s general attitude to his subject matter – his tone – fundamentally baffling, but also compelling. He is clearly alarmed and amused by bourgeois society, and trying to see – to insist on – masquerade and massacre as its necessary two faces. But how seriously? How compassionately (remembering sweet Jesus, but also his vision of Christ’s entry into Brussels)? With what admixture of class panic?

It happened that the day I first visited the Academy show I was reading Dostoevsky’s novella The Eternal Husband, and as I stood in front of The Intrigue I couldn’t shake off the memory of Velchaninov’s dream:

He dreamed of some crime he had committed and concealed and of which he was accused by people who kept coming up to him. An immense crowd collected, but more people still came, so that the door was not shut but remained open. But his whole interest was centred on a strange person, once an intimate friend of his, who was dead, but now somehow suddenly had come to see him. What made it most worrying was that Velchaninov did not know the man, had forgotten his name and could not recall it. All he knew was that he had once liked him very much. All the other people who had come up seemed expecting from this man a final word that would decide Velchaninov’s guilt or innocence, and all were waiting impatiently. But he sat at the table without moving, was mute and would not speak. The noise did not cease for a moment, the general irritation grew more intense, and suddenly in a fury Velchaninov struck the man for refusing to speak, and felt a strange enjoyment in doing it. His heart thrilled with horror and misery at what he had done, but there was enjoyment in that thrill. Utterly exasperated, he struck him a second time and a third, and, drunk with rage and terror, which reached the pitch of madness, but in which there was an intense enjoyment, he lost count of his blows, and went on beating the man without stopping. He wanted to demolish it all, all.

I think this gets us into Ensor’s world. Proximity and crowding are two of his themes, especially in The Intrigue – above all the kind of proximity that confirms each individual’s deep loneliness. Masks only make the choreography more distinct. Of course what the ‘it’ ultimately amounts to, for people like Velchaninov, will never be clear – that is partly Dostoevsky’s point. And Ensor similarly was a sufferer from rage he couldn’t put a finger on – he was a frozen, frightened ‘case’ (like Kafka or Maeterlinck). There is always too much guilt and horror to go round: putting the names ‘sin’ or ‘godlessness’ or ‘bourgeois society’ to them is bound to be desperate shorthand. But the atmosphere of the it – that’s what counts in art. That’s what art ought to register. And for a while Ensor’s did.

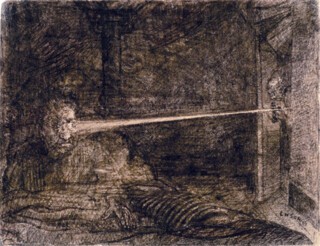

There is a tremendous drawing in the exhibition which the catalogue entitles, peculiarly, Revelatory Heart. Something went astray here along the road from American to French back to English. The episode Ensor is illustrating comes from Poe’s story ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’: we are at the moment when the murderer manages to focus a beam of light in the darkness, searching for his victim, an old man asleep; and the beam bounces off the victim’s wide-awake eye. It is a typical Ensor subject: something we’d assumed was inanimate or insensible suddenly looks back at us with malignant life. There are other things based on Poe in the exhibition – notably a sizzling Hop-Frog’s Revenge. But I prefer Ensor’s glum version of the Poe crime story. Again the bleakness of the bedroom is essential. The ghosts and masks have all but vanished in the murk. The Poe of the hellish city whodunits, then, seems relevant to Ensor (not forgetting his Masque of the Red Death); and the Dostoevsky of The Double and The Eternal Husband (with maybe The Grand Inquisitor’s Christ thrown in); and the Redon who lithographed Les Fleurs du mal and Flaubert’s Temptation of St Anthony; and Cézanne swearing to the end of his life that he would do a full-scale Apotheosis of Delacroix. ‘J’entends ignorer mes influences.’ It all adds up, in Ensor’s painting, to a heart-stopping sane brew.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.