A couple of nights before I first saw the Richter show at Tate Modern I had been at the Festival Hall listening to Boulez conduct his Pli selon pli. I felt then, as the octogenarian directed us through his atrocious and wonderful labyrinth, that it was sheer luck – the luck of a lifetime – to have caught this last intransigence of modernism on the wing. When the soprano sang the final word of Mallarmé’s ‘Un peu profond ruisseau calomnié la mort’, with her voice disappearing in a ghost-story gasp, I thought I heard a whole culture refusing to go gracefully. The German’s tone is different from the Frenchman’s: more wounded and muffled and sardonic and naive, less pedagogical, less deeply immersed in the agony that gave rise to modernism in the first place. Richter’s Duchamp is a poor substitute for Boulez’s Mahler. But the two old men are comparable. Hearing the one and looking at the other I was sure that the nature of a vanished century, and the survival of the claim to art it gave rise to – the full recognition of the improbability of the claim – were at stake.

The retrospective of Richter’s work at Tate Modern is a great event. It is beautifully hung by Mark Godfrey and Nicholas Serota: packed tight and relentless room after room, by the end exhausting, and in this entirely true to Richter’s half-century of effort. The selection of work could not be better, with things often seen before enlivened by juxtaposition with the unfamiliar (to me), and the sequence presented with the minimum of wall-label stage direction. MoMA in New York has lent the show its necessary still centre, the terrible grey room entitled 18 October 1977, which approaches (any verb here will be too weak and too strong) the evidence left behind from the deaths and destruction of the Red Army Faction. The loan is generous – the 15 paintings would be any museum’s pride – but one senses that MoMA’s curators saw immediately that this was a one-time chance.

Listening to Boulez, I immediately feel that only a fool could doubt that this is the necessary and sufficient response to the death of tonality, and to the death of ‘expressiveness’ it enacted. This may be my ignorance of music – I’m easily overpowered. With Richter there can be no such certainty. I cannot imagine a viewer emerging from the rooms at Tate Modern and being sure that Richter’s endless hovering around the fact of the photograph – his subservience and aggression towards the medium – had solved, or even properly framed, the problem of ‘painting and figuration’ in our time. Nor do I think that a viewer will come out of the show convinced – or even decided that Richter means us to be convinced – that the artist’s version of abstract painting really does dig back into the lost territory of painterly ‘expression’ (or immediacy, or individuality, or sheer delight) to mine it again against the odds. Is this the difference between music and painting? Perhaps. Music seems to me ultimately nothing if not, on the other side of modernist doubt and pedagogy (and those have been fiercer in music than any other art form), unforgivable raw emotion. Painting by contrast really can, for reasons I am unable to fathom, make its uncertainty – its long depressive state – into something beautiful as opposed to correct or clever. John Cage, for some of us, is an even lesser god than Duchamp, but in the final room at Tate, where a suite of big abstracts done under Cage’s auspices is hung, it does not matter. The imperfect lusciousness of the canvases, each nearly ten feet square (the way, in the best of them, dubiousness and hedonism coexist), leaves the ‘Is it Art?’ starting point far behind.

The show is enormous. All a review can hope to do is ask a few leading questions of it, and most of these have been asked before, in a literature that is already overwhelming (and often good). Right from the start of the exhibition, in the two small rooms – they feel appropriately stifling – full of Richter’s mostly monochrome oils done from photographs in the 1960s, two questions occur. First, what is Richter’s immersion in the mostly dreary photographic material for? Second, what does his paintings’ elaborate distancing from the feel of the photographic – the blurring and smearing, the way black and white seem to drift towards a weaker, less inflected, more listless overall grey – end up achieving? What does the artist do to the ‘photographic’ and the ‘painted’, as he receives the categories from the culture at large?

The questions crop up naturally, but this does not mean they are the right ones. Not on their own, anyway, and not asked separately. The idea of working from the photograph seems in Richter, again from the beginning, to have been bound up with the idea of almost painting things out. A kind of botched concealment comes from the photograph as if it were its inner perfume. The photographic seems much of the time to be another word for the lifeless. Some orgy … Some tiger … The draining away of chroma is a figure for a general lapsing out of spatial (and therefore social) relationship. The liberated young women displaying their genitals and the uncle smirking in his Nazi uniform are equally near or far away, equally ‘scandalous’ (it says here in the paper), equally unfelt. The photo-language is archaic: that is what the dim monochrome suggests to me most powerfully. It speaks to a false fixation on the past – maybe that of a refugee from East Germany, maybe that of post-Hitler Germany in general. Family secrets, hearts of darkness, a desperate cocking a snook (is that the right word?) at one’s compromised parents. Richter’s is a world where even fetishism does not work: the shine on the nose of appearance, which one or two canvases bring on emblematically – ineffectively – can do nothing against philosophy, or art after Auschwitz, painting its grey on grey. That cliché again …

Perhaps I have pulled out the stops of despair and disorientation in the last paragraph, but not by much. Richter’s 1960s is a horrible decade. His past in the DDR seems to cling to him, and always he turns from the imagery of the future on offer in the world he has chosen – the new freedom and equality of the children in the porn shots – with a shudder. The Red Army Faction is near. There are some cityscapes painted in 1968 and 1969, in particular Stadtbild SL (from which Luc Tuymans learned brilliantly), where all the achieved non-life of modernity is painted with a truly chilling lack of affect, as if seen by a sociopath looking through the sights of a gun.

Two points follow. First, this is the matrix from which the big coloured abstracts emerge in the following decade: they make no sense, in my view, unless they are seen against this background of grey panic. Second – same point, essentially – the 18 October 1977 paintings are long prepared. They return to Richter’s fundamental, and persistent, sense of his own time. Whether painting in general, for him, is essentially a way of keeping that sense from overwhelming him – he sometimes says so, but what else would he say? – or of showing the sense (the erasure) infiltrating everything, even the boldest and blithest claim to pleasure: that is the question the show goes on not answering. To its credit, I think.

The word ‘blur’ has come up. ‘Richter’s blur’, it is called in the literature. Again, the term may be insufficient. When one gets to the moment in the show when Richter reinvents his ‘blur’ in the context of abstract painting – the two versions of Abstraktes Bild from 1977 are particularly astonishing, and still hard to look at – it is immediately clear how far from a description of what happens in the paintings, and what its effect might be on the viewer, the monosyllable is. Critics have come up with alternatives. In the context of abstraction – that strange episode in art’s endgame – all the suggestions seem charged. Have we to do, for instance, with some kind of deliberate loss of focus or of register? Maybe with a form of willed inaccuracy on the artist’s part. Or even vagueness. This last, it might seem, is very much not a modern art value; though that might mean Richter was right to try to make it one. I like the story Richard Rorty told against himself late in life, when he heard that a philosophy department had just hired someone whose speciality was vagueness, and he raised an eyebrow. ‘Dick, you’re really out of it,’ his host said. ‘Vagueness is huge.’

Emptiness, by contrast, is a condition that modernism treasures. Pli selon pli reminds one of that. But I am not aware of an artist before Richter who tries to make pictorial intensity out of a kind of fullness – a stuffed-fullness, or at least a heavy impenetrability – that has no specific substance to its parts, no feeling of its constituent colours and textures having been hit precisely by the maker, and fixed inevitably, in all their unique particularity. (This is different from large generalisation, which abstract painting thrives on. Clyfford Still and Mark Rothko generalise, but they expect us to assent to the idea that breadth of touch and emptying of detail are ways, for them, towards specificity of feeling – emotion really happening – rescued from culture-industry mush.) Richter is the painter at the furthest remove, I reckon, from Adorno’s sense that the whole and only point of art is always to find – to instantiate – concrete particularity in a world of false vividness. Vividness for Richter, if it comes, will have to have falsity written deep within it. I guess this is the strong side (the genuinely disabused-of-illusion side) of his Duchampianism.

The 18 October 1977 series was painted in 1988 and first shown the following year. It provoked a good old 19th-century storm of criticism. Richter had tried to sanctify a bunch of irrelevant psychopaths, some said; he had wallowed in an episode the nation was right to put behind it; he had sucked a set of revolutionaries, however misguided and ruthless, into the grey maw of his private (petit bourgeois) nihilism. And so on. The fact that many of the criticisms were crude and crass does not mean that all of them were. ‘Wallowed’, more or less without the pejorative, is not a bad descriptive term. The out-of-focus Funeral, largest and muddiest of the paintings on show, the one that might seem to be reaching, at least in terms of scale and subject, for the public register of Goya’s Third of May, brings on (in me) a feeling of utter impotence and incomprehension. Perhaps Richter is a petit bourgeois nihilist: the question the righteous leftist commentators might have asked themselves, however, is what the nerveless attitude allows him to ‘say’ about neo-Leninism; whether nihilism (whatever its class ascription) is now the only vantage point from which the ghost dance of revolution can be chronicled.

I think the Red Army Faction paintings are Richter’s masterpieces, but I mistrust that judgment in myself. Richter’s art had been waiting, so it seems, for this occasion, and critics like me (with their own settling of accounts with the 1960s still incomplete) could not bear, but could not put down, the result. One side of me still pulls away from the force field. It is too obvious, the funeral hymn: too belated, too grey and neutral, too Olympian, too ready with affect after the danger has passed. Maybe nobody wanted to see the familiar greyness and vagueness of Richter’s painting – these essentially small things, these facts of art – suddenly lungeing for the epic. Surely Richter of all people had taught us that metaphor in painting – the colour grey being ‘lifeless’, for instance – had to be deeply embedded, almost indecipherable, if it was to work. But in 18 October 1977 metaphor is rampant. Grey does the work of mourning. It and the blur stand for dirty, but also sterilised, secrets. Lifelessness is literalised: it appeals to us: it is given a look from beyond the grave. Politics is a foul turbulence, with atrocity happening off-stage. These are mugshots from an anarchist archive. Concealment. Obstruction. Fading. Take a look at the pseudo-poignant record player (a record player!) with Winterreise or ‘Street Fighting Man’ stopped on the time-turntable.

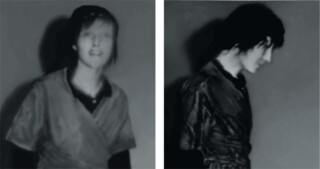

I do not think I am inventing, or working up, these moments of revulsion. And they do not go away: there is no artistic aufheben. Our dealings with Baader and Ensslin and Meinhof, and with Richter’s daring to have them be Art, are – horrible word, but completely appropriate – compromised. The way to an attitude to revolution is via some weird, unjustifiable mixture of distance – ‘I know nothing, really, just glimpse the odd misery through the murk’ – and full-blast foghorn pity and fear. Don’t ask me why the latter movement is irresistible, but it is. The three paintings of Gudrun Ensslin called Gegenüberstellung are as close to a conjuring of the dead as I have seen in painting. ‘Confrontation’ is a perfectly good translation, but so would be the more matter of fact ‘Opposition’, which hangs on to the noun’s inner dynamics of ‘facing’, ‘standing across from’, ‘being in front of’ (that damn camera). I hate the soft focus of Opposition 1. It seems to me to hedge its humanitarian bets. But maybe it was necessary as a starting point – an emotional nowhere – from which Ensslin in all her craziness and vulnerability and courage and self-righteousness could then emerge, to address us, to stand opposite and laugh. The two later Oppositions, I sometimes think, are the only pictures of people done in our time that the future will care to look at – though not for long. They are Géricault’s Mad Portraits reinvented.

Writing on Richter inevitably gravitates to the Baader-Meinhof paintings, but should not end with them. For they only make sense – become more understandable, or maybe unforgivable – in relation to the big blazing abstractions in the rooms next door. The two modes glower and wink at one another. It was touching a few weeks ago to hear Benjamin Buchloh – a longtime friend and critic of Richter, with whose interpretations of his painting Richter has sometimes struggled – saying that he thought now he had got it wrong, in a famous interview with the artist, when he called his abstractions parodies. No doubt the word is too conclusive. But the feeling that Richter’s relationship to abstraction is deeply peculiar will not go away. Is he serious, the paintings seem to ask. And what is seriousness, in abstraction? Perhaps it involves calling into question the kind of seriousness abstract art usually goes in for – its Red Army Faction sententiousness, that is.

What, on the evidence, does Richter take the ‘abstract’ to be? He knows, for sure, what it had meant to his great predecessors: for them, in the high days of modernism, it had been essentially a way out of the generic and secondhand towards the actually made and felt in painting, here, on the surface, with this and this material. It aspired to a made-ness made without rules, without any notion of ‘the picture’ preceding the picture itself. Abstract painting’s strength, we could say, was the way it inherited the central 19th-century dream – of pictures, whatever was meant by ‘pictures’, coming to exist in the moment, with weather and light forcing them into being. If the moment teased and elated the picture sufficiently – this was the hope – there might be a chance of its escaping the half-world (the greyness) of ideology. Richter divests himself of this hope, this strength. The vagueness of his first abstractions, it follows, is as strange and reckless a turning – a weakening – as any artist has risked.

Does the risk pay off? Not always, I think, but sometimes triumphantly. In the best abstractions weakness is all. Of course no artist could have gone on decade after decade painting in this manner without reinventing a version of abstract art’s original false confidence. Weakness in Richter, when we get to the 1980s, is often replaced by blatancy and the blaring of trumpets. Paintings like Yellow-green (1982) or June (1983) are at one level – I hang onto Buchloh’s intuition – parodies of Kandinsky’s or de Kooning’s charged vividness. Parodies, and therefore acts of homage, shaking their heads in wonder and disbelief (and impatience and envy and tolerant amusement) at abstraction’s first impudence and naivety. Perhaps we could say that abstract art had always been parody – parody Plato, parody Monet or Moreau, parody Songs without Words – and what Richter did was return and return to the fact, as puzzle and instigation.

The show has many other aspects. I have said nothing, for example, of the mostly small or mid-size canvases done ‘from’ colour photographs from the 1970s on: intimate, homely, often unsettlingly harmless things – Betty, Barn, Candle, Flowers, Meadowland, wife and baby, old friends. Seeing them in the vicinity of Gudrun Ensslin is bound to make the harmlessness uncanny. Not ironic or clinical or coldly ‘aesthetic’, in my view – the candle shines steadily, Betty (Richter’s daughter) is nobody’s puppet – but nonetheless pictures that ask us, in a just detectable whisper, not to believe in them too much. The most tender and touching of the Betty paintings – oil on wood, 12 by 15 inches, with Betty’s small face tipped horizontal, as if resting on the floor, filling the rectangle, spilling towards the picture’s bottom edge – is hung low in a room filled with shrieking abstractions. At first I thought the contrast histrionic; but I soon gave in. For it seems truly part of Richter’s way of proceeding that always in him the abstract and figurative edge towards some such stage-managed Confrontation – intimacy versus alienation, flesh-paleness versus ‘virtual’ pink and yellow, love versus kicks.

Over the past two decades Richter’s work has revolved around a new type of abstraction, with almost the look of a signature style. For the master of incompatibilities, this is worrying. The paintings are mostly large, with what appear to be one-colour or two-colour backgrounds, across which has been dragged (by a series of squeegees, some of them giant) an abraded curtain of greens, greys, reds, purples, electric yellows. It is a strange world. We might be looking into a window from a speeding car, or scanning a surface through an electron microscope, looking for structure and not finding it. Again, there is something in this I recoil from. The word ‘glazing’ comes up; but glazing – that precious resource of oil painters from Burgundy on, in which colour was given depth and intensity by being made to shine through a foreground translucency – now botched, magnified, hypertrophied, presented to us as ‘device’. (‘Glazing’ as in eyes glazing over.) The paintings, alas, have a corporate glossiness. But Richter does not stand still. In the Cage room I found myself suddenly reminded of collages made in Paris in the mid-1950s, by flâneurs obsessed by the capital’s billboards – borrowing their layers of torn, spoiled, rainsoaked movie posters and truss advertisements. They were sentimentalists, these French (Raymond Hains and Jacques Villeglé pre-eminently), ragpickers straight from the pages of Spleen de Paris. My guess is that Boulez would have disapproved of them. But it was moving to see their great dream of the barrières – their Hugo-hymn to the old city’s scruffiness and provinciality and shameless loveliness – resurfacing in Richter as he gave abstraction its deathblow.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.