Cézanne, whose work was the touchstone for critical thinking and writing on art for more than a century, cannot be written about any more. After a few minutes in the exhibition at the Courtauld (until 16 January), surrounded by Card Players and Smokers, one understands why. The mixture of seriousness and sensuousness in the paintings – I am tempted to say, in the best, of lugubriousness and euphoria – is remote from the temper of our times. So too is the quality of grim, eager pursuit of perfection within a narrow range: ‘the difficult thing is to prove what one believes,’ Cézanne wrote to one correspondent, ‘so I am continuing my researches.’ The work has a 19th-century flavour. The 20th century revered it, but did the reverence do much good? (Artistically, that is, as opposed to art-critically.) I would fool nobody if I pretended not to be one of Cézanne’s worshippers – unreconstructed, and all the more fanatical for knowing that the cult is dead – but I have no way to answer the contemporary shrug. I almost prefer it to the residual symptoms of Cézannoia, especially the English variant of the condition. There’s a bit of all this about in the room at the Courtauld. Well-bred pagans hanging on to the old gods in face of Christianity (or postmodernism), exchanging glances in the deserted temple. My grey beard had company.

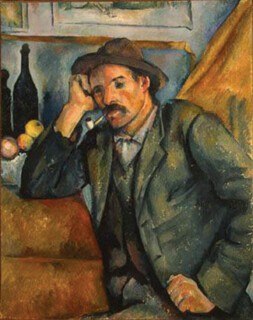

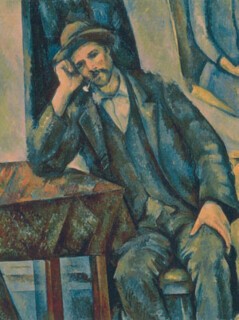

Oh, but the pictures survive it all. There is an astonishing trio of large portraits of a middle-aged man, probably a farm labourer, in his Sunday best – loans from Mannheim, St Petersburg and Moscow – that it is worth travelling the earth to see hung in a row. They are the most complex depictions of ‘an ordinary fellow’ to come down to us from the recent past. A peasant, I suppose we have to call him. An actor in that great historical turning point at which life on the land hung on – just – to its age-old texture and structure, and intellectuals sang its praises. Over the century of Cézanne worship, readers were regularly treated to stuff about Cézanne’s human subjects not having been granted humanity and character, and their coming across much like objects in a still life; and one great advantage of leaving the age of Cézanne behind is that this kind of judgment has come to seem, if not incomprehensible, then massively wrong. The three peasants at the Courtauld – obviously the Mannheim and St Petersburg paintings are of the same man, but maybe the Moscow one is a touch younger – are not demonstrative. They take up the pose of Dürer’s Melencolia 1 (well, not quite) but it is hard to think of them brooding miserably on a life of toil, or even on a form of life grown old. They are not producing ‘themselves’ for the painter-viewer. Which is to say, they come to portraiture from a world – from a class position – just a little outside the genre’s suppositions and implicit bargains. That is the point. They are awkward, resplendent, self-possessed men. Working men, enduring the attention of the odd son of a dead banker (who paid well). They are, it now seems possible to see, monuments to a specific way of life – to another kind of balance between inwardness and exteriority – but we are treated to that monumentality precisely because the ambition to ‘represent the peasant’ was utterly foreign to Cézanne’s cast of mind. The ‘peasant’, for him, emerged from the given. And of course the banker’s son, the lycéen with his quotes from Lucretius and Baudelaire, agreed with his class’s best thinkers that the given reality of the world was atom, photon, touch, opacity and transparency, unique sensation, lived intuition of space. In the St Petersburg painting the red of the peasant’s lip bleeds – explodes – across his chin, neck, earlobe, shadowed forehead. In the Moscow version, the man’s hand on his thigh is like a huge pair of callipers, holding and measuring the cylinder for eternity.

Because the social and human resonance of paintings like these has now become visible to us, art historians have lately been trying to explain how the resonance came about. Efforts have been made to reconstruct the ideology of a nervous, somewhat literary rentier from Aix in the time of Mistral. The blood and soil regionalism of one or two of Cézanne’s writer friends seems relevant. This is certainly a welcome change from the modernist hermit-martyr cooked up by l’art pour l’art admirers in the early 1900s, but I’m not sure I buy it. It seems to me to get things the wrong way round.

Cézanne was obsessed by looking and painting. He wanted to do the full range of things that painting was capable of – no one was ever more certain of his place in the great tradition – and that included large-scale portraits and scenes from common life. Sitters were available. Putting them round a table playing cards was appropriate: it was the kind of thing they did together, and the concentration required by the game would be enough to rub the edges off the men’s fidgeting and self-consciousness in the studio and get them to sit still. Then photon, touch, sheen, opacity could be focused on. And out of these would be assembled – this was always the ultimate goal of painting as far as Cézanne was concerned – a particular spatial order (which certainly had room for kinds of disequilibrium) in which the tempo and tone and lived reality of the scene would be on view. Of course that included an intuition of the actors’ ‘form of life’. But the intuition had to emerge from the given of perception. It had to be built from the photons. If we wanted, for explanation’s sake, to posit a kind of (misleading) temporality to the process, we might say that out of an accurate registration of optical appearance there would emerge a correct – which is not to say, familiar – form for the sitter’s disposition, his way with his body. And therefore also for the way he was in the habit of presenting himself to others, assuming the frame of the room, the game, the background of life in common. And in that presentation of self – that wholly material acting-out of inwardness – the ‘background of life in common’ would become not background but a touchable, sensual thing on the surface, here where we are. (All of the Smokers and Card Players are meditations on the paradox of ‘background’ in painting.) In a word, a form of life is there in the given, if the given is grasped naively enough. Or we could say, again with the three Smokers in mind, that a form of life is nothing but the specific, eccentric ‘characters’ who embody it. The three men are the same man. The three men are different. They glory in their class identity, and they couldn’t give a toss about it. Funny thing, leaning on a table with a cold pipe in one’s teeth.

But aren’t you making Cézanne out to be much the same modernist magician as his enthusiasts always have? A form of life emerging from a pure perceptual array! What about everything in the Smokers that reeks of forethought – of some kind of predetermining frame, ideological or otherwise? What about the cleverness of the fragments of paintings hung on the wall to the sitters’ rear? In the Hermitage Smoker, a group of black bottles and flushed fruit turns out to be a painting of part of a painting produced 20 years before (now in Berlin): an ominous, doom-laden vision of familiar things, done in the great thunder and lightning impasto of Cézanne’s first (I hate ‘early’) style. The Moscow Smoker’s elbow goes off at a neat tangent into a long vertical borrowed from the edge of a curtain, and over to the right he is given a woman partner on the wall, on a piece of canvas whose corner refuses to stay flat. And then there’s the crystalline hardness of all the tables, carved and chiselled until they become Dürer-type complex solids, capable of cutting their human users. (Compare the tablecloths in the Orsay and Courtauld Card Players, which take the little tables they’re on top of for a magic carpet ride.)

Here is where writing on Cézanne should stop. Blather about these sorts of detail being so many tokens of ‘paintedness’ has me immediately switching off my metaphorical hearing aid and humming the ‘Ça ira’. It’s as stale as the talk about the (undermining of the) omniscient narrator in the novel. Surely it is obvious by now that the cleverness, in both cases, is not merely or primarily reflexive: it is integral to the business of capturing a form of life – precisely at its moment of disintegration. I’m certain of this, but don’t know how to say more about it. Supposing I made a verbal equation of some sort between the pictorial geometry in the Smokers – hard-edged, shifting, elaborate but clunky, compressed, solid as a rock – and the 19th-century peasantry in the flow of time. Ouch! Off goes the hearing aid again. Because language like this misses the point. Cézanne is massively sure, no doubt, that his painting can make a connection between geometry and history; but only because he is at the same time so confident that he can keep the two utterly separate, incongruent. Facts of making are different from facts of understanding – that is what 19th-century painting is all about – but each is completely at the other’s service. The cards are little pictures (thank God Cézanne resists playing up this cliché), the players have the weight of a world on their shoulders. It won’t last long, the world in question. And maybe pictures – picturing – will disappear with it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.