Picasso was a painter of themes. Themes, not subjects or ‘subject matter’: he pointed out the difference to André Malraux in 1937, just before Guernica left his studio for the Paris World’s Fair. Malraux had remarked that though neither of them put much stock in ‘subject matter’, on this occasion, in painting the great mural, his subject had served Picasso well (‘Cette fois, le sujet vous aura bien servi’). Picasso disagreed: far from supplying him with a subject, Guernica had given him a theme. What did he mean? Not simply an idea or a topic, but a human universal to be expressed symbolically: death as a skull, Picasso said, not a car crash. ‘What he considered themes (I quote) were birth, pregnancy, suffering, murder, the couple, death, rebellion, and, perhaps, the kiss … Nobody could be ordered to express them, but when a great painter encounters them, they inspire him.’

Picasso’s themes focus on the extremes of intimate bodily experience. All are fundamental to human existence. Their prominence in the European pictorial tradition, though, is less secure. Consider the familiar topics his inventory omits: on the one hand, gods and heroes, no matter how sacred, triumphant or transcendent; on the other, human vanity, ritual sacrifice and the violence of the hunt. In Guernica, all are absent. Instead, as Malraux tells it, to speak of ‘subjects’ to Picasso was to provoke him into cataloguing the crucial stages of the human experience, cradle to grave. In that context the relevance of revolt or rebellion seems an afterthought, a mere add-on to the primal cycles of survival. In any event, revolution is not what the painting’s stark pantomime depicts. Instead it conjures the explosive clash of life and death in a frozen tableau.

Within this radical opposition, animals and women are the ones who survive. It is their lot to suffer and mourn. The women bare their breasts. A child is dead. With these motifs Picasso transforms thoughts of the kiss and the couple, birth and pregnancy into a larger drama: in Guernica, human reproduction is exposed to mortal threat. Yet this dimension is absent from most accounts of the painting. Why? Does the omission stem from an unacknowledged embarrassment at the insistent bodiliness of the artist’s chosen terms? Or has Guernica’s place in the politics of its moment, not to mention its role in later struggles against violence and injustice, overshadowed the biological politics it brings to the fore?

Guernica was bombed by the Nazi Condor Legion on the afternoon and evening of 26 April 1937. It was a Monday, market day in the Basque town. News of the attack reached Picasso through a report published two days later in the Communist newspaper L’Humanité. The lead article – ‘Mille bombes incendiaires lancées par les avions de Hitler et Mussolini’ – was accompanied by a photograph of two women lying dead in a street. Not, however, a street in Guernica: the photo records an attack on another Spanish city. The reader isn’t told which one. Hence the generalities provided in the accompanying caption: ‘Ci-dessus, quelques femmes – des mères sans doute – abbatues au cours d’un bombardement.’ Female victims were mothers, ‘sans doute’. How could it be otherwise, when the bearing of children defined women’s role? At a moment when the damage wartime violence inflicted on innocent victims became a Republican leitmotif, women are assumed to be mothers, and mothers cannot – should not – die alone.

Picasso’s painting was intended to take sides in the same combat. Yet the image it offers did not develop ‘sans doute’; instead its composition was transformed through rapid revisions, not merely of particular details, but of the painting’s overall spatial logic and dramatic force. The experimental process through which these changes were accomplished was established long ago. But no one has yet explored the various ways in which Picasso’s work on Guernica reveals, or betrays, the layers of complexity buried in his list of themes. These move well beyond the obvious fact that naissance and grossesse were both bodily processes with a recurring role in his life. Eighteen months before the bombing of Guernica, Picasso’s mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter had given birth to a daughter, his first daughter and Walter’s only child. But more important to the story of the mural, if one follows its genesis in the drawings of April and early May 1937, is the larger question Picasso’s themes presented: how can the maternal body, whether pregnant or the source of the infant’s sustenance, be made to bear the marks of death? How could the painter find the means to convey such mortal threats?

The opening towards the theme of maternity came late in the day. The art historian Herschel Chipp has shown that, before the bombing, Picasso had planned an enormous depiction of an artist’s studio, painter and model included; it wasn’t quite room-sized, but was carefully plotted to dominate one long wall in Josep Lluís Sert’s Spanish Pavilion at the World’s Fair. Not only did he think through the necessary dimensions, but in a pen and ink drawing of 19 April he sketched the installation he envisioned: the huge canvas would be flanked by two symmetrically placed pedestals, each bearing a bust of Marie-Thérèse. It seems a strange notion: the result oddly formal, even artificial, as if the artist were using sculpture to frame, and thus enshrine, his picture’s painted world.

The day before, Picasso had completed a series of drawings that led him to this stage, 12 in all, each numbered and dated; it is as if, in his eyes, the end was in sight. Then he put the project aside until after Guernica was bombed on 26 April. On 1 May 1937, he began all over again, to produce the mural we know.

Yet despite the enormous disjunction between the first and second ideas, it would be wrong to conclude that Picasso started from scratch the second time around. During the Civil War, for a Spanish artist who supported the Republic to make a mural depicting a painter in his studio could only have seemed an evasion. I suspect that Picasso began to realise this in the course of mapping that first idea. Early in the process, his composition – it included the figure of a painter, a model reclining on a canapé, and a picture window – received two crucial additions: an electric ceiling lamp and a spotlight shining from its place on the studio floor.

As the ensuing drawings demonstrate, Picasso then began to ring the changes on the spectacular qualities implied by this compositional idea. The placement of the spotlight began to vary, modifying the triangular path of its light. Soon enough, this triangle was played off against the horizontal rectangle of the picture window at the right of the studio space. Both devices – light and window – anticipate strategies deployed in the finished mural. Look at the planes and vectors that explode the familiar fiction of the studio as an isolated cell. Without warning, it becomes a rudimentary structure neither inside nor out. The artifice required to bring off this ambiguity still seems marvellous, befitting a painting that puns on the confusions born from illumination of all kinds. Their impact is enough to splinter the painting’s already fragile structure. There was no going back.

To look again at the set of ‘studio’ studies is to grasp how the impasse was reached. The problem derived partly from Picasso’s worry about his painting’s eventual destination. The wall he was allotted in Sert’s pavilion was not only long but low, and though there was a window on the right-hand side, the ground-floor site was dark enough that floodlights would be needed. Picasso’s solution, a painting 2.2 times as wide as it was high, was longer than the longest wall in his studio on the rue des Grands Augustins. He planned accordingly.

His carefully calculated proportions dictated even the first design. And unlike Picasso’s late 1920s treatments of the studio interior – its space flattened and patterned by the arbitrary impact of light – the mural was conceived as a three-dimensional illusion of space, though not in standard shoebox mode. Instead its volume was to be oddly irregular, deeper along one side than the other, as well as capable, or so Picasso imagined, of containing an imaginary arc of the sort that could be inscribed by a compass with its point fixed where artist and viewer were to stand.

This may sound complicated, and there is every reason to believe that Picasso thought so too. The last in the sequence of drawings made on 18 April, the sheet labelled XII, shows a collection of diagrams: two views in perspective, one partly scribbled over and abandoned; two plans of the site as seen from above; an image of the depicted space of the mural, seen head-on and shown as if it could open up the wall behind it; finally, two segmented circles that plot angles of vision from a single vantage point – the viewer’s position, presumably, but also that of the artist. In the last drawing in this sequence, the still more hectic pen and ink drawing of 19 April, any pretence of stability had become unbalanced in a clash of motifs: hammer and sickle meet paintbrush and painter, and he is now she.

There is no document that states why Picasso abandoned his first idea. All that remains is the set of studies. But it seems clear from the drawings that having returned to the familiar subject of the studio, Picasso now found it intractable, and ultimately insoluble. Against the light of the window was pitted the spectacle of the spotlight; against the depth of depicted space was an unruly internal geometry; and within all this, the figures of both painter and model were subjected to the increasing pressure of their assigned places. It is striking that in the final drawing, XII, the figure of the model, initially envisioned reclining on a sofa, has become comically misshapen: woman as a gourd or a phallus, or both. As for the painter, whose presence had seemed essential, s/he has been all but erased by a slicing plane of light.

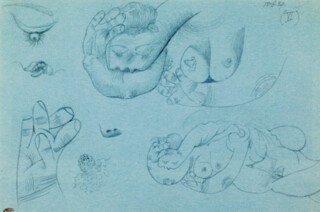

Why did Picasso find this project so difficult? Why did he put it aside? The question isn’t unreasonable given that in the decades before and after Guernica, he relied on, even revelled in, the subject of artist and model. On this occasion, however, he denied himself such self-reflexive subjects, presumably realising they could not meet the demands imposed by the commission. How else to explain the absence of traces of the studio composition in the final design? The central pyramid of light has gone. Lacking, too, are the references to pregnancy and birth – or so it seems. But both are uncannily present in the sixth drawing in the series, a set of studies of a sleeping Marie-Thérèse, all precisely pencilled on a single sheet. Her mouth is open, both breasts are visible, and her head is cradled in one arm. This may seem entirely in keeping with the conventions of artists’ drawings of their models. Yet this drawing is far from usual. Picasso isolates her sensory organs: eyes, mouth and tongue, vulva, hands and fingers, nostrils and nipples. In every case, the detail defamiliarises. Hands become udders, eyes resemble spiders, the tongue is a knife-blade, and as for the close-up of a nipple, its aureole and milk ducts have begun to bubble and foam. Chipp describes these details as betraying a ‘terrible ferocity’, an ‘ambiguous, as yet unnamed, threat or promise of violence’. I prefer to wonder whether these features invoke at least some of the characteristics of the body of a lactating mother. And might Picasso’s ‘ferocity’ register his alienation from a body he can’t control?

A month later, the theme of the artist in his studio was a thing of the past. German bombs had carpeted Guernica, machine guns had strafed the onslaught’s survivors, and on 1 May Picasso returned to work. Again he made a series of sketches in quick succession, continuing late into June. By the end of July, the mural had been installed, photographed and discussed in the press. Then and since, there was much to say. But what has never been analysed is how bombs, suffering and women – ‘des mères sans doute’ – go together in the final work.

Of Picasso’s nearly fifty studies for the final mural, eight make those connections painfully clear. They also show that right at the start of things the only female figure in the picture was the woman with the lamp: part genie, part allegory, her bare breasts serve to unmoor her bodily presence, perhaps even to set her afloat. As a figure of truth, she had no body at all. And her weightlessness meant that when the maternal body did enter the composition in two studies (numbered 12 and 13, both from 8 May), embodiment in general – the horror of the body’s vulnerability – enters with it. For the first time blood is present, collecting between the wailing mother’s breasts and her dead infant’s body, pooling at her knees. In the next drawing, a pen and ink study dated 9 May, a kneeling woman, mantilla floating, again clutches her dead infant’s body against her breast. Blood flows from around her hand, down the child’s arm and legs, and collects in a dark pool on the floor. In another sketch, the woman climbs a ladder while clasping the corpse in one arm. Blood pours from a wound in her neck. Here, the orbs of the mother’s breasts – as well as the baby’s head – amplify her belly’s pendant curve. Is this grossesse? If so, its companions are suffering and death.

Picasso returned to this same pairing in a further drawing, sketch 21. It takes its orientation from the upright ladder, but while the first version used pencil, the sequel turned to vivid crayon. The difference is vast. Blood red explodes against the deathly green outlines of the bodies; purple and blue fight against brilliant orange and yellow; dark pencilled vectors press against an apocalypse of light. And yet nothing from this spectacle of terror made its way into the starkness of the final work.

There are two more drawings from this month-long series in which mother and child are reprised (36 and 37, both made on 28 May). Neither is particularly close to the mural’s final composition, but they show Picasso continuing to advance the terror and pathos war visits on maternity and birth. In sketch 36, which again shows a mother with her lifeless baby, both figures are traced in an interlinking outline, as if to suggest one body, not two. And as in the sketch that follows, a spinning blue shape, neither egg nor orb, whirs through the space. Womb or bomb? It is both.

The same deadly shape reappears in sketch 37, this time in both black and blue. Now its dual function is explicit: the blue disc attaches to the figure of the mother, while the dark whirlwind hovering before her has yet to hit ground and explode. Above it hangs what may be a single heavy breast. Or is it another lethal weapon, as its ribbed and reinforced casing would seem to suggest? And what are we to make of its nipple, which resembles the nursing nipple so myopically examined in Picasso’s pencil study of his sleeping mistress from 18 April, labelled Study VI. Black bomb, blue womb: one seems barren, the other brings death. Would it be right to say that oblivion comes late to this screaming mother? Her baby already hangs limp, impaled by the point of a sword. The sword drips; blood seeps through her fingers. Her own death approaches. A lock of hair has been snipped in advance.

Picasso’s drawings, we might say, took up the problem of depicting what happens after the children are dead. His answer shows them mourned by mothers made monstrous by their loss. That nothing in the finished mural reaches the radical intensity of these studies makes sense. What Picasso needed to arouse in his viewers was horrified revulsion, but also identification. The bombing of Guernica unleashed destruction, but also a struggle to survive. Picasso’s women and animals are the protagonists of that uneven contest: they scream and stagger, mourn and burst into flame. These figures may have survived the conflagration, but their bodies bear the marks of the horror. No one escapes. Here is the mother with the corpse of her baby, wailing at the pitiless sky. From the start her role in the composition was repeatedly studied. It is her child who bleeds, her child who dies, her mouth that screams. Yet in the mural the mother is frozen and the baby limp. The bomb’s impact, by contrast, travels through the composition, resounding again and again. Flames and tongues and nipples come to knife-points. Palms and soles are slashed with cross-cuts. The body of the stumbling woman on the right is in ruins, crushed and deflated. The full is now flat. What remains is eerily transparent, with bones and entrails visible within.

Consider what happens to the breasts of the stumbling woman, which are fully exposed as she rushes forward. Like several of the mothers in Picasso’s preparatory drawings she is subject to one last deformation, the shockingly robotic, or perhaps machinic, mutation of her breasts. Their once sensate flesh has been remade as metal fixture – a trigger or a stopper, perhaps, but nothing sustaining of life. Such a device wouldn’t look out of place on a gun, or might be used in arming a missile or grenade. Within this obscene conception lurks the spectre of a fully weaponised fertility – the mother as bomb. A similar menace bristles in the features of other bodies in the mural: the ghastly dagger tongues of both humans and animals; pricked ears; sharp-spiked fingers and toenails. Most explosively, the weaponry (part mine, part mace) in the corner of the lamp-bearer’s window should be read as two breasts and a hand. How difficult they are to decipher, and how appalling the vision when at last we make it out. Is this Picasso’s answer to the Nazi vision of the armoured fascist male? Here, at the empathetic heart of his huge composition, the bombs hold sway.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.