J.M.W. Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed: The Great Western Railway hangs in a corner of Room 34 at the National Gallery on Trafalgar Square. The painting remains close to where it was first exhibited in 1844 when the Royal Academy occupied the gallery’s east wing. ‘There comes a train down upon you,’ Thackeray wrote after seeing the painting. ‘The viewer had best make haste … lest it dash out of the picture and be away to Charing Cross through the wall opposite.’ The National Gallery has been refashioned, the RA has moved to Piccadilly, but the train in Rain, Steam and Speed is forever hurtling towards Charing Cross.

The only other painting at the National Gallery that comes close to its depiction of speed is Titian’s Death of Actaeon, which shows Diana, the goddess of hunting, running through woods to witness Actaeon’s death: she has already transformed him into a stag as punishment for coming across her and her nymphs bathing. His own hounds have caught up with him, they don’t recognise their master and they’re about to tear him apart – just as certainly as the train will destroy a hare in Rain, Steam and Speed.

‘Always take advantage of an accident,’ Turner once said. ‘A painter can only represent the instant of an action, and what is seen at first sight’ was another of his aphorisms, one that he borrowed from Gotthold Lessing or John Opie, magpie that he was. ‘Every glance is a glance for study,’ he also said. The scene in Rain, Steam and Speed is of an imminent death, the instant of an action caught by a glance. A train rushes across a bridge and is bearing down on a hare that’s running over the washed-brown bed of a railway track. The hare isn’t immediately obvious because it is partially obscured by the driving rain. The train will catch up with the hare and kill it: there’s no escape, the track is encased by walls. The hare’s typical act of self-defence, to turn back on itself so dramatically that it throws off its pursuers, marvelled at by hunters for centuries, isn’t available: the locomotive blocks its path. ‘Each outcry of the hunted hare/A fibre from the brain does tear,’ Blake said, but this hare’s death looks as if it will be instantaneous.

‘The world has never seen anything like this picture,’ Thackeray said. Commenting on the writer’s reaction to the painting, John Barrell wrote (in the LRB of 18 December 2014) that Thackeray ‘won’t have to wait for the tide of modern art to flood in to appreciate what Turner has done. It’s 1844, and he’s got it. Turner is not out of his time; he and Turner are contemporaries.’ The tide of modern art wasn’t long in coming: in the first Impressionist salon in 1874, George Braquemond showed an etching of Manet’s Olympia alongside an intriguing version of Rain, Steam and Speed. He captured some of the elements of Turner’s title – the wind-driven rain slashes across the bridge – but his train appears as static as a Monet locomotive idling at the Gare St Lazare. He also left out the hare.

Kenneth Clark described Rain, Steam and Speed as the ‘most extraordinary’ of Turner’s paintings. ‘I suppose that everybody today would accept it as one of the cardinal pictures of the 19th century on account of its subject as well as its treatment.’ That subject is often seen as the ascendancy of man-made industrial society and the obliteration of the old natural order. Andrew Wilton, the author of Turner in His Time, considered the painting’s perspective as indicative of the triumph of the new: ‘The plunging diagonal line that cuts across the familiar location here is an emphatic demonstration of how the new technologies of the age imposed a precise geometric order on the pastoral scene.’

New as the geometric order may be, chasing after hares is as old as any ancient rite, but who or what is hunting the hare in Turner’s painting? Is it just a train, and how familiar, really, is that location? You can shut down the iconographical interpretation of art, with its artistic and literary allusions, and concentrate instead on Turner’s painterliness, but with Rain, Steam and Speed you might be missing something if you do. What happens if you look at it as a mythological painting, like Diana and Actaeon, a study of the hunter and the hunted, the hubris of the one and the elusiveness of the other?

The word ‘chase’ can refer to the pursuers of hunted animals: it can also mean the animals that are pursued as well as the territory over which such hunting goes on. One word can stand for all the elements of the scene. The contest between the hunted and the hunter was, unsurprisingly, familiar to Turner. In his time, hares were a trophy for the successful hunter, as well as gifts – in his letters, Turner often thanks his correspondent for a present of hares. They feature in many 17th and 18th-century still lifes: dead hares are a motif at the Wallace Collection, and you’re now more likely to come across a hare in art than you are anywhere else. The appetite has gone.

Turner fished and shot not because he was conspicuous and wanted to show off but because he wasn’t and he didn’t: he was essentially frugal and self-sufficient, for all of his success. ‘He threw a fly in first-rate style,’ an acquaintance said of his fishing; he caught the gait of a fisherman ‘wherever the rod is introduced into his pictures’. Some contemporary manuals considered the sport a form of self-improvement, but Turner didn’t fish to make himself a better man. He fished to fish, and portrayed it as such: a fishing scene on Clapham Common, painted in 1802, is matter-of-fact, even banal. At the house in Twickenham he built for himself, he stocked a pond with fish he’d caught from the Thames.

When Turner stayed with his patron and friend Walter Fawkes at Farnley Hall, north of Leeds, he fished on the River Wharfe and shot on the moors. He painted or drew what he caught or killed – trout, roach, woodcock, red grouse, snipe. He painted the head of a heron with a dead fish in its beak – one of a series of paintings he contributed to the Fawkes Ornithological Collection, a four-volume album. The Fawkes family sent Turner game every Christmas. ‘By to-morrow’s coach I shall send you a box containing two pheasants, a brace of partridges, and a hare – which I trust you will receive safe and good,’ Fawkes wrote in a letter of 1818. ‘We have tormented the poor animals very much lately and now we must give them a holiday.’ Turner wrote to Fawkes’s son at the beginning of 1851 to thank him ‘for the brace of longtails and brace of hares’.

In Grouse Shooting on Beamsley Beacon (1816), a watercolour at the Wallace Collection, Turner portrayed himself and Fawkes on the moors above Bolton Abbey. Fawkes is on a horse, looking on as Turner, with gun poised, moves forward through the heather towards two dogs on the scent for grouse. In Woodcock Shooting on Otley Chevin (1813), a man on a wooded hillside stands in the foreground, signalling with his raised arm that a bird has been driven from cover and taken flight. A gunman to the left is about to take aim; the bird’s flight that instant is obscured by a tree. Turner has exaggerated the woodcock’s size: it is the very last moment before it will be shot. ‘His pictures denote a foregone conclusion,’ Hazlitt said of Poussin: that would be one way to describe Woodcock Shooting on Otley Chevin, too – or Rain, Steam and Speed.

Until the fox became the object of the chase in the mid-19th century, hares were as central to hunting as deer. ‘Of all the chases, the hare makes the greatest pastime and pleasure,’ wrote the anonymous 18th-century author of The Huntsman. According to Gaston Phoebus’s 14th-century Livre de chasse, the hare is ‘king of all venery’. Turner drew and painted several hare chases apart from Rain, Steam and Speed. In one of them, a hare runs over the spot where Harold was felled at the Battle of Hastings. In Apollo and Daphne (c.1837), Daphne prevents Apollo from helping a dog pursue a hare, foreshadowing the god’s doomed pursuit of the nymph herself, who chose to be turned into a tree rather than be caught. In a watercolour called Colchester, Essex (c.1825) a hare runs away from two dogs. A man on a horse in the background on the other side of a pond looks on with his arms raised – a running hare was a sign of forthcoming calamity. A woman has come out of a wooden house: she, too, has her hands raised in alarm. A man follows a dog that has set out in pursuit, though neither looks to have any chance of catching the hare.

Hares were said to dance, widely believed to change sex, and like witches appeared out of nowhere only to vanish just as fast. Hares had an ‘indefatigable sense of seeing’, according to The Huntsman. It was a popular belief that they slept with one eye open. ‘Fearful of every danger, and attentive to every alarm, the hare is continually upon the watch,’ Thomas Bewick said in his History of Quadrupeds (1790). A hare was ‘a great delicacy among the Romans’, but it was a sacred animal for the British, ‘who religiously abstained from eating it’ – a ‘hare-lipped’ child was said to be the consequence of a pregnant woman eating hare. Another fear was that the eater would become as timid as hare. Not so sacred or worrisome: hare recipes were, until recently, familiar to British cookbooks.

If the hare in Rain, Steam and Speed is the quarry, who is the hunter? That’s a question with an obvious answer – a train – but is Turner’s train just a train? I didn’t think to ask that second question until someone told me they felt like the hare in Rain, Steam and Speed, with the burden of work at their back. I wanted to be reassuring, to say the train has no chance of catching the hare, and then I looked at the painting once more.

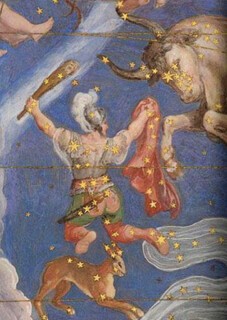

The answer to the identity of the hunter in Turner’s painting can be found in the night sky, where the constellation Lepus (the Hare) lies below Orion. On the painted ceiling of the Sala del Mappamondo – the Room of the Map of the World – in the Villa Farnese, Orion wields a club as he follows the hare which he’s destined never to catch. The Villa Farnese is a pentagonal palace in the hill town of Caprarola, north of Rome; it’s famous for its gardens and for its frescoes, and for an astonishing vista from its loggia towards the Italian capital, which Turner sketched when he went to Italy in 1828.

The place of Orion and the hare in the sky is fixed, but the myth of the giant hunter is not stable. Homer, Ovid, Boccaccio and the 16th-century poet and mythographer Natalis Comes all wrote about Orion. He appears in the account of the skies written by Hyginus in the second century AD. Keats wrote of ‘blind Orion hungry for the morn’ in Endymion, while Turner’s near contemporary Richard Horne wrote an epic poem, Orion, the year before Turner exhibited Rain, Steam and Speed. Charles Lamb’s version of the Odyssey appeared in 1808: ‘Then came by a thundering ghost, the large-limbed Orion, the mighty hunter, who was hunting there the ghosts of the beasts which he had slaughtered in desert hills upon the earth.’

In one version of the myth Diana was tricked into killing Orion by her brother Apollo, jealous of his sister’s affection for the hunter. He asked her to fire an arrow at an object out in the water without telling her it was Orion’s head. In other versions, Orion is killed knowingly by Diana. In yet another, he is stung to death by a scorpion, and both are thrown into the sky by Zeus and given after-lives as constellations. (Scorpius and Orion are never seen in the sky at the same time.) At Caprarola, Orion also appears in a panel below the mural on the ceiling called the Scorpion. He pursued the Pleiades – the seven sisters – for five years only for Zeus to intervene and make them a constellation, too. One of the sisters was Merope, also the name of the daughter of Oenopion, king of Chios, whose father was Bacchus – the Chians were, so it was said, the first people to cultivate the vine and Oenopion means ‘wine-faced’ if not drunk. Oenopion asked Orion to rid his island of wild animals. This Orion did, but then, when he was drunk, according to Hesiod, he raped Merope. In revenge her father blinded him. Unable to see and therefore to hunt, Orion went in search of Diana who he hoped would bring back his sight.

Poussin’s Blind Orion Searching for the Rising Sun was owned by one of Turner’s heroes, Joshua Reynolds. The painting shows the blind giant striding across the country towards the east: standing in the clouds is Diana, who looks on as if she’s been expecting him. On Orion’s shoulders is the dwarf-like figure of Cedalion, whom the hunter had asked to help guide him to the dawn. In a famous essay about Poussin’s Orion, Ernst Gombrich listed the mythological sources available to Poussin, and attacked the ‘bewildering farrago of pedantic erudition and uncritical compilation’ that characterised the scholarship about this picture. Gombrich was sure Natalis Comes’s Mythologiae had informed Poussin’s version of the myth, but did he go too far in his ironing-out of the sources for Poussin’s painting? Myths by definition have multiple sources. In the Scorpion panel of the Sala del Mappamondo, Orion marches forward with his three dogs; he is unaware of the scorpion lying in wait on the ground in front of him. Like Poussin’s representation of him, Orion is a giant: he dwarfs the hunting men in the background. His only equals in the picture are Diana and Apollo, only unlike them he isn’t a god. That is his human problem – his pride. His belief in his omnipotence has got the better of him.

Reynolds bought the painting in 1758; it was sold after his death, and a subsequent owner put it on display in London in 1821. Hazlitt went to see it:

Nothing was ever more finely conceived or done. It breathes the spirit of the morning; its moisture, its repose, its obscurity, waiting the miracle of light to kindle it into smiles; the whole is, like the principal figure in it, ‘a forerunner of the dawn’. The same atmosphere tinges and imbues every object, the same dull light ‘shadowy sets off’ the face of nature: one feeling of vastness, of strangeness, and of primeval forms pervades the painter’s canvas, and we are thrown back upon the first integrity of things.

That isn’t a bad description of Rain, Steam and Speed, either. Thackeray wasn’t wrong when he said the world hadn’t before seen a painting like it: they hadn’t, but in another way they had, if they had seen Poussin’s Blind Orion.

Francis Chantrey , the sculptor, is supposed to have rubbed his hands in front of Turner’s blazing suns as if his friend’s pictures radiated the heat of glowing embers. Turner asked Chantrey to bury him wrapped in one of his sun pictures to keep his dead body warm in the grave. Rain, Steam and Speed isn’t one of those paintings. There’s nothing scorching about it: there’s no beam of setting or rising sun exaggerated by its reflection on water; the sky and the clouds aren’t the blood orange of an electric fire. But the painting possesses heat: without it there would be no rain, steam or speed.

‘They are pictures of the elements, of air, earth and water,’ Hazlitt wrote of Turner’s paintings. ‘The artist delights to go back to the first chaos of the world, or to that state of things where the waters were separated from the dry land and light from darkness … All is without form and void.’ That isn’t entirely true: Turner represented the man-made world, it’s just that other forces – history, mythology, nature – tend to dominate or belittle it. But in Rain, Steam and Speed there is also the raw shock of the new. It depicts a black locomotive, pulling a number of open-topped silver-wheeled carriages packed with passengers, rushing out of a scene without a horizon onto a heavy brown bridge in windswept rain where it closes down on a hare that has no hope of outpacing or avoiding it. There’s no driver in sight: the menace of this faceless train is the menace of a faceless train. Or a blind driver. The paint on the front of the locomotive, the dabs of red and white, may or may not represent the engine’s fire chamber with its front hatch thrown open, but in any case the paint screams danger. The red and white, set against the black iron of the engine, are the colours of a hunter or a soldier – someone accustomed to soot, flesh and bone. Thomas Lawrence’s portrait of the Marquess of Londonderry, hanging in the same room at the National Gallery, is a painting of a general dressed for battle in red, white and black.

The passengers in the open-topped carriages resemble the voyeurs in Manet’s Bar at the Folies Bergère. In their hats and coats, they are travelling on the Great Western Line when being out in the open and coursing through the country was billed as a thrill in its own right. J.C. Bourne’s History and Description of the Great Western Railway (1845) was an account of the ancient history of the country that these passengers would cut through, accompanied by maps and engravings of the line, as well as its rolling stock. The maps show off the shallow gradient of the line, which was known as Brunel’s billiard table.

One of Bourne’s prints is of the engine house where the Firefly locomotives were kept. Seven foundries built the Fireflies, the replacement for an earlier class of engine called the Star. They were given names from classical mythology: Achilles and Actaeon, Castor and Cyclops, Medea and Electra –and Orion. ‘But still the heart doth need a language, still/Doth the old instinct bring back the old names,’ Schiller wrote. The translation is by Coleridge. That old instinct for old nomenclature was common practice on the Great Western Railway. Printed timetables told passengers to keep an eye out for animals of the chase and the hounds and horses that followed them, as if the journey were a tour through the hunting rites of the old country, a mythological England you tore through, hauled at speed by engines named after gods and monsters.

Thick white cloud at the top of the picture is broken by patches of blue here and there; the surface of the painting is rough. Paint has been applied with a palette knife: in places it looks as if Turner may have run his fingernails over the paint. The cloudscape resembles the paintwork of Rembrandt, Andrew Wilton says, a reminder of Turner’s debt to old masters.

The hare’s nose was once about to fall off. ‘New flake loss from the end of the nose of the hare reported while on display,’ it says (in biro) in the painting’s conservation file at the National Gallery. ‘Retouched with water colour’ was the remedy. The canvas is made up of two pieces stuck together: ‘Both fabrics extremely brittle and perished. Paint typical of late Turners; smooth in some places and heavy impasto in others.’ The bluntness of conservation notes is refreshing. Charles Eastlake, the artist, friend of Turner and first keeper of the National Gallery, wrote a note to a conservator in 1857: ‘Three puffs of steam, already left behind the engine, as most clearly expressing the idea of speed.’ He went on to say how important it was that those puffs are seen. They also look like Orion’s belt.

To the right of the railway bridge, below a blue and indecipherable shade, close to the edge of the canvas, a man walks behind two animals. Turner scholars say the man is a ploughman with two horses. C.R. Leslie saw Turner put the last touches to Rain, Steam and Speed on ‘varnishing day’, just before the opening of the show, when artists made last alterations to their work. Turner ‘talked to me every now and then’, Leslie said, ‘and pointed out the little hare running for its life in front of the locomotive on the viaduct … The hare and not the train I have no doubt Turner intended to represent the “Speed” of his title, the word must have been in his mind when he was painting the figure of a man ploughing, “Speed the Plough”.’

Speed the plough? There’s no reason to think the hare better represents speed in the painting than the train, and there’s not much reason to think the man in the lower right corner is a ploughman. Turner made an etching in 1818 of a ploughman working in the shadow of Eton College Chapel; he looks nothing like the man in Rain, Steam and Speed, who looks more like a hunter carrying a long-barrelled rifle, out with his hounds and about to walk into the woods.

The bridge the train is crossing has always been assumed to be the railway bridge at Maidenhead. Lady Simon said she had been in the same compartment as Turner on a Great Western train from Exeter to London, and he told her that Rain, Steam and Speed was realised after he put his head out of the window of a train as it passed over the Thames at Maidenhead. As the painting itself shows, carriages often did not have roofs in the early 1840s: you had no need to stick your head out of a window because there were sometimes no windows. Brunel’s bridge at Maidenhead, still the longest, shallowest brick arch in the world, is striking for its economy: its investors insisted the arches should be supported by wood – until they saw the wood served no purpose. Turner’s bridge, by contrast, is heavy, even chunky, and the one pillar visible to the viewer looks like a fat thigh thrust down into the river. That may be the effect of foreshortening, or perhaps Turner’s bridge isn’t – or isn’t only – Brunel’s.

There’s also the problem of the point of view; there’s no embankment at Maidenhead from which you can look down on the bridge. In the first volume of Modern Painters, published in 1843, John Ruskin explained the relationship between the painter and the viewer: ‘He places the spectator where he stands himself; he sets him before the landscape and leaves him. The spectator is alone. The artist is his conveyance, not his companion, – his horse, not his friend.’ In Rain, Steam and Speed, however, Turner has placed his spectator in thin air.

Is the background to the picture the landscape near Cliveden – or Cliefden, as it was called before the name was tarted up by the Astors – or is it an imaginary landscape, made up of elements common to many of Turner’s paintings? To the left of the bridge, through a watery haze, a group of brightly dressed figures in red, white and blue stand on the water’s edge, and may or may not be waving at the train. They’re no more than blots, but they are distinctly people, and there seem to be seven of them, like the Pleiades.

Out on the river, the other side of the bridge from the huntsman, are two figures in a boat, one of them is under an umbrella; Turner had been known to fish with his umbrella. Beyond the fishermen is a stone bridge, so typical of Turner that it looks as if he’s quoting himself. ‘The Bridge in the Middle Distance’ is the title of one the engravings in Turner’s Liber Studiorum, the series of prints he made to show off his artistic ability. In her essay on the significance of castles, towers and bridges in romantic art, which she also called ‘The Bridge in the Middle Distance’, Adele Holcomb interpreted Turner’s bridges as ‘metaphors of transcendence … they are connected to the symbolism of hope.’ There seems to be no hope for the hare on its bridge – except that Orion, trapped in the night sky, is unable to catch up with it. The train is forever hurtling towards Charing Cross; the faintly seen hare survives.

So why this chase scene, why depict Orion as a train? Was Turner saying that an old mythological story could be represented in new terms, or was the painting made with a more specific idea in mind? The year before Turner exhibited Rain, Steam and Speed, Ruskin had published the first volume of Modern Painters, a book he had wanted to call ‘Turner and the Old Masters’ until his publishers asked him to change it. Ruskin went after Turner as if he was in pursuit of him, and it’s possible to see Rain, Steam and Speed as Turner’s response to Ruskin’s book.

Modern Painters, Ruskin said, is an exploration of ‘the effect of greatness upon the feelings’; Turner, he wrote, was ‘the greatest artist who has embodied, in the sum of his works, the greatest number of the greatest ideas’. Ruskin met Turner for the first time in 1840: ‘Introduced today to the man who beyond all doubts is the greatness of the age; greatest in every faculty of the imagination.’ The prophetic intelligence of the artist, and the insights they found in nature which weren’t available to anyone else, was the German-inspired idea that Ruskin applied to Turner.

Ruskin was one of the first people to see Rain, Steam and Speed. He went to a private view at the Royal Academy in 1844: ‘A memorable day, my first private view of the Royal Academy. I stayed to the very last, and shall scarcely forget the dream-like sensation of finding myself with Rogers the poet’ – it was in the illustrations to Samuel Rogers’s long poem Italy that Ruskin had first encountered Turner’s art – ‘not a soul beside ourselves in the great rooms.’ But that was all he had to say. He never wrote a word about Rain, Steam and Speed, and he was never convinced that any train, or any idea of the ‘scientific people’, as he scornfully described them, was worthy of artistic representation. The second edition of Modern Painters hints at Ruskin’s reticence about the representation of industrial technology. ‘If we are now to do anything great, good, awful, religious, it must be got out of own little island, and out of this year 1846, railroads and all.’

The Fighting Temeraire, Turner’s picture of a relic of the Battle of Trafalgar, is typically said to represent his ambivalence about the Industrial Revolution: the old ship is hauled to a wrecker’s yard in Rotherhithe by a new black steam-powered tug. But Turner was no Luddite. And while there’s no evidence he was a follower of Saint-Simon, who believed that the industrial society to come would be shaped by engineers and artists, he was a founding member of the Athenaeum Club, which was as strong an expression of Saint-Simon’s industrialisme as you could find in London. If artist and engineers were going to bring about Saint-Simon’s revolution, Rain, Steam and Speed: The Great Western Railway – Turner’s painting of Brunel’s engineering – was that revolution in action.

Beneath the old warship and its tug, beneath the Thames itself, Brunel was building the first tunnel under a river, from Wapping to Rotherhithe. Rotherhithe was the home of a wrecker’s yard but in 1838 that place name was synonymous with what was going on underground and out of sight.

Ruskin and Turner quarrelled in 1845-46 – over what, Ruskin never said. ‘Turner had made up his mind that I was heartless and selfish,’ he wrote to his parents. Twenty years later, Ruskin had a falling out with Thomas Carlyle over an article written by Ruskin that Carlyle believed mischaracterised him. When Carlyle wrote to Ruskin to complain, Ruskin threatened to end their friendship and alluded to his earlier falling out with Turner. ‘I always suffer this kind of thing from those who I have most cared for, and then I cannot forgive, just because I know I was the last person on earth they ought to have treated so – Turner did something of the same kind to me – I never forgave him – to his death.’

Turner wrote to Ruskin in November 1848 from the Athenaeum:

My dear Ruskin,

!!! Do let us be happy

Yours most

truly and sincerely

J M W Turner

Ruskin’s reply, if there was one, hasn’t survived.

Ruskin’s awkwardness about technology was hardly unique: the 19th-century literature on the monstrosity and evils of steam engines is large. Carlyle described travelling by train as the nearest thing to taking a journey with Faust on the Devil’s mantle. The National Gallery’s collection is an expression of that reticence about modern technology as a subject for art. The depictions of machinery and industrial landscapes are few – there are more still lifes of fruit, fish and half-peeled lemons.

Room 34 is also known as the Great Britain Room. Stubbs’s Whistlejacket is at its centre. The prancing horse is set against a sandy backcloth, and in its glossy, muscular and expensive way looks like the artwork for a cover of Vanity Fair. Real, glossy, successful – Whistlejacket was all three, even if the zestful sounding name is taken from a sticky Yorkshire drink made from treacle and gin. In 18th-century thinking, horses were said to be inherently competitive, born to race out their ‘unconquerable ambition’, ‘love of glory’, the lust to be ‘foremost in the course’. On seeing Stubbs’s painting, the stallion is supposed to have attacked the portrait he mistook for a rival.

Reynolds, Gainsborough, Constable, Raeburn, Lawrence, Wilkie and Wright of Derby are all represented in Room 34. Raeburn’s portrait of two young men out hunting shows one with his bow drawn, the other waiting in the shadows. On bright afternoons, when the lamps are turned off and the room is lit only by daylight filtered through the frosted glass of the ceiling, the whites in some of the pictures become outstanding: electric light tends to kill the luminosity in Gainsborough’s portraits of white-haired women and men.

There are seven Turners. To the left of Rain, Steam and Speed are The Fighting Temeraire and The Evening Star; the reflection of Venus on a calm sea is more obvious than the planet in the evening sky. In Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus, the Cyclops has been blinded by Ulysses and his men, who are escaping in their boat. On either side of the north entrance to the room are Calais Pier and Dutch Boats in a Gale, pictures of chance and fate – for Boccaccio, shipwrecks were emblematic of failed love, although in these scenes the boats may yet survive.

The colours in Rain, Steam and Speed are dull, even the whites, but the picture is said to be in good condition. The wall note beside the painting says: ‘A steam engine advances across a bridge in the rain. In front of the train, a hare runs for cover. The scene has been identified as the railway bridge over the Thames at Maidenhead. The picture demonstrates Turner’s ability to capture atmospheric effects in paint.’ The note adds that it is an oil on canvas, its National Gallery number is 538, and it’s part of the enormous bequest Turner made to the nation.

Orion was the hunter killed by Diana who was thrown up into the sky to become a constellation (so the story goes), who would forever chase a hare he has no hope of catching, who appears in the skies clearly only between the autumn and spring equinoxes, and whose appearance in September and disappearance in March is associated with storms as well as the beginning and the end of the hunting season. Orion had three fathers: Poseidon, Apollo and Zeus – or in Roman mythology, Neptune, Apollo and Jupiter. In his essay on Poussin’s Blind Orion, Gombrich wrote that the ‘slightly repulsive apocryphal story … of the giant’s procreation … to Natalis Comes clearly signifies that Orion stands for a product of water (Neptune), air (Jupiter) and sun (Apollo)’. If you recall the names of those three gods and what they represent and then look again at the title Turner gave his painting of the Great Western Railway one thing seems to follow another.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.