Sometime in the 1970s, at the home of the feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey, I found myself in the company of another critic, who had just returned to London from the Berlin Film Festival. Over dinner he took pleasure in regaling us with stories of the male to female transsexual prostitutes he had met on the city’s streets, and how difficult it was to ‘complete’ the transaction since the transsexual body interprets the surgically created vagina as a wound which it tries to close. The nature of his interaction with these women was unclear, but his delight in telling the tale of sexual encounters which, by his account, could only be sadistic on the part of the man and painful for the women involved, was repellent. He was boasting. Doubtless he thought he was promoting their case. He registered my disapproval. Twice I declined when he offered to refill my glass with red wine. Finally I put my hand over the glass to make myself clear. Refusing to take no for an answer, he proceeded to pour the wine over the back of my hand.

Just a few years earlier, in 1969, Arthur Corbett, first husband of the famous male-to-female transsexual April Ashley, sought an annulment of their marriage on the grounds that at the time of the ceremony, Ashley was ‘a person of the male sex’. In the course of the proceedings, Corbett – ‘The Honourable Arthur Cameron Corbett’, as he introduced himself to Ashley after initially using the alias ‘Frank’ – presented himself as a frequenter of male brothels and a cross-dresser who, when he looked into the mirror, never liked what he saw: ‘You want the fantasy to appear right. It utterly failed to appear right in my eyes.’ He then explained how, from their first meeting at the Caprice, he had been mesmerised by Ashley. She was so much more than he could ‘ever hope to be’: ‘The reality … far outstripped any fantasy for myself. I could never have contemplated it for myself.’* It took a while for Ashley, along with her medical and legal advisers, to realise what Corbett was up to (nine medical practitioners gave evidence in court). He was, in her words, portraying their marriage as a ‘squalid prank, a deliberate mockery of moral society perpetrated by a couple of queers for their own twisted amusement’.

Corbett’s ploy was successful: the marriage was annulled. The case is commonly seen as having set back the cause of transsexual women and men for decades. Transsexual people lost all marriage rights for more than thirty years. The decision ruled out any change to their birth certificate, a right they had enjoyed since 1944, and thereby denied them legal recognition of their gender. In 1986, female-to-male transsexual Mark Rees, in the first challenge to the ruling, lost his case at the European Court of Human Rights against the UK government for its non-recognition of his status as male, loss of privacy and barring his marriage to a woman. Only with the Gender Recognition Act of 2004 was the law changed to permit transsexuals to marry, on condition that they first obtain a Gender Recognition Certificate. The House of Commons report Transgender Equality, published in January this year, notes that the medicalised certificate pathologises transsexuality and ‘is contrary to the dignity and personal autonomy of applicants’. Describing the act as pioneering but outdated, it calls for a further change in the law. ‘Not since the Oscar Wilde trial,’ Ashley comments on Corbett v. Corbett in her 2006 memoir, The First Lady, ‘had a civil matter led to such socially disastrous consequences.’

For Justice Ormrod, the case – ‘the first occasion on which a court in England has been called on to decide the sex of an individual’ – was straightforward. Because Ashley had been registered as a boy at birth, she should be treated as male in perpetuity. The suggestion that she be categorised as intersex was dismissed: medical evidence attested that she was born with male gonads, chromosomes and genitalia. Although there had been minimal development at puberty, no facial hair, some breast formation, and what Ashley referred to as a ‘virginal penis’ because of its diminutive size, the judge also ruled out these factors (he believed the breast formation had been artificially induced by hormones). That Ashley had undergone full surgical genital reconstruction – there had been some (unsatisfactory) penetrative sex between her and Corbett – made no difference: ‘The respondent was physically incapable of consummating a marriage as intercourse using the completely artificially constructed cavity could never constitute true intercourse’ (what would constitute ‘true intercourse’ is not specified). Ashley was not, to Ormrod’s mind, a woman. This was more to the point, as far as Ormrod was concerned, than asking whether or not Ashley was still a man. At first he had been sympathetic to her, but as the hearing proceeded, he became progressively less persuaded of her case: ‘Her outward appearance, at first sight, was convincingly feminine, but on closer and longer examination in the witness box it was much less so. The voice, manner, gestures and attitude became increasingly reminiscent of the accomplished female impersonator.’ In the words of one of the expert witnesses, her ‘pastiche of femininity was convincing’ (you could argue that a convincing pastiche is a contradiction in terms).

Ormond may have found for the plaintiff on the grounds that Ashley couldn’t fulfil the role of a wife (‘the essential role of a woman in marriage’), but it is obvious from Corbett’s statements that this was never exactly what he had had in mind. For Corbett, Ashley was not an object of desire, but of envy. He coveted her freedom, her scandalous violation and embodiment of the norm. She was someone he wanted to emulate. Corbett’s wording is precise. Ashley was his fantasy or dream come true, the life he most wanted, but could not hope for, for himself: ‘The reality … far outstripped any fantasy for myself. I could never have contemplated it for myself.’ He did not want her, as in desire; he wanted to be her, as in identification (in psychoanalysis this is a rudimentary distinction), or rather the first only as an effect of the second. In this, without knowing it, he can be seen as coming close to obeying a more recent transsexual injunction, or piece of transsexual worldly advice. As Kate Bornstein, one of today’s best-known and most controversial male-to-female transsexuals, puts it towards the end of her account of her complex (to say the least) journey as a transsexual: ‘Never fuck anyone you wouldn’t wanna be.’ (Bornstein’s memoir is called A Queer and Pleasant Danger: The True Story of a Nice Jewish Boy who joins the Church of Scientology and Leaves Twelve Years Later to Become the Lovely Lady She Is Today.)

One of the ways trans people challenge the popular image of human sexuality is by insisting, in the words of the writer and activist Jennifer Finney Boylan, that ‘it is not about who you want to go to bed with, it’s who you want to go to bed as.’ This, it can be argued, is the province of gender: how, in terms of the categories of male and female, you see yourself and wish to be seen. In fact the modern distinction between sex and gender was created with reference to transsexuality a matter of months before the Corbett-Ashley case by the psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Robert Stoller, who proposed the distinction in his 1968 study, Sex and Gender – the second volume was called The Transsexual Experiment. For Stoller, gender was identity, sex was genital pleasure, and humans would always give priority to the first (many transsexual people today say the same). Talk of a gender dysphoria syndrome was therefore as inappropriate as talk of a ‘suicide syndrome, or an incest syndrome, or a wanderlust syndrome’. Stoller’s most famous transsexual case was Agnes, who had secured genital reassignment surgery having duped Stoller and his associate Harold Garfinkel into believing that her female development at puberty was natural (they diagnosed her as a rare instance of intersex in which an apparently male body spontaneously feminises at puberty). Five years later, she returned to tell them that since puberty she had regularly been taking oestrogens prescribed for her mother: ‘My chagrin at learning this,’ Stoller wrote, ‘was matched by my amusement that she could have pulled off this coup with such skill.’

Cruel and outdated as the Corbett case may be, it makes a number of important things clear. The transsexual woman or man is not the only one performing; she or he does not have a monopoly on gender uncertainty; what makes a marriage is open to interpretation and fantasy – there is strictly no limit to what two people can do to, and ask of, each other. Above all perhaps, the Corbett case suggests that a transsexual person’s enemy may also be their greatest rival, embroiled in a deep unconscious identification with the one they love to hate; while the seeming friend, even potential husband, may be the one furthest from having their interests, their chance of living a viable life, at heart. After the annulment, Ashley fell back into penury, where, like many transsexual women, she has lived a large part of her life (her fortunes fluctuate wildly). Both Mark Rees and Juliet Jacques, the author of the 2015 memoir, Trans, fall in and out of the dole queue. Even before the trial, Ashley’s career as one of the UK’s most successful models had been brought to an abrupt end when she was outed by the press. Up to that point, like many transsexual people who aim to pass, she had lived in fear of ‘detection and ruin’ (in the words of Garfinkel, one of the first medical commentators to write sympathetically about transsexuality).

As Susan Stryker and Aren Aizura write in their introduction to the second of Routledge’s two monumental Transgender Studies readers, published in 2006 and 2013, however obsessed we may be with the most glamorous instances, most transsexual lives ‘are not fabulous’. In 2013 the level of unemployment among trans people in the US was reported to be 14 per cent, double the level in the general population; 44 per cent were underemployed, while 15 per cent have a household income of less than $10,000 compared to 4 per cent of the general population. Jacques gives statistics showing that 26 per cent of trans people in Brighton and Hove are unemployed, and another 60 per cent earn less than £10,000 a year. This is also the reason so many, especially male-to-female transsexuals, take to the streets (to survive materially but also to raise the money for surgery). ‘Suddenly,’ Jacques writes, ‘I understood why, historically, so many trans people had done sex work … I started to wonder if sex work might be the only place where people like me were actually wanted.’

Transsexual people are brilliant at telling their stories. That has been a central part of their increasingly successful struggle for acceptance. But it is one of the ironies of their situation that attention sought and gained is not always in their best interest, since the most engaged, enthusiastic audience may have a prurient, or brutal, agenda of its own. Being seen is, however, key. Whatever stage of the trans journey or form of transition, the crucial question is whether you will be recognised as the other sex, the sex which, contrary to your birth assignment, you wish and believe yourself to be. Even if, as can also be the case, transition does not so much mean crossing from one side to the other as hovering in the space in between, something has to be acknowledged by the watching world (out of an estimated 700,000 trans women and men in the United States, only about a quarter of the trans women have had genital surgery). Despite much progress, transsexuality – ‘transsexualism’ is the preferred term – is still treated today as an anomaly or exception. However normalised, it unsettles the way most people prefer to think of themselves and pretty much everyone else. In fact, no human can survive without recognition. To survive, we all have to be seen. A transsexual person merely brings that fact to the surface, exposing the latent violence lurking behind the banal truth of our dependency on other people. After all, if I can’t exist without you, then you have, among other things, the power to kill me.

The rate of physical assault and murder of trans people is a great deal higher than it is for the general population. A 1992 London survey reported 52 per cent MTF and 43 per cent FTM transsexuals physically assaulted that year. A 1997 survey by GenderPAC found that 60 per cent of transgender-identified people had experienced some kind of harassment or physical abuse.† The violence would seem to be on the rise. In the first seven weeks of 2015, seven trans women were killed in the US (compared with 13 over the whole of the previous year). In July 2015, two trans women were reported killed in one week, one in California, one in Florida. In the US just 19 states have laws to protect transgender workers (only in 2014 did the Justice Department start taking the position that discrimination on the basis of gender identity, including transgender, constitutes discrimination under the Civil Rights Act). The House of Commons report Transgender Equality notes the serious consequences of the high levels of prejudice (including in the provision of public services) experienced by trans people on a daily basis. Half of young trans people and a third of adult trans people attempt suicide. The report singles out the recent deaths in custody of two trans women, Vicky Thompson and Joanne Latham, and the case of Tara Hudson, a trans woman who was placed in a men’s prison, as ‘particularly stark illustrations’ (after public pressure, Hudson was moved to a women’s jail). ‘I saw,’ Jacques writes in Trans, ‘that for many people around the world, expressing themselves as they wished meant risking death.’

In 2007, Kellie Telesford, a trans woman from Trinidad, was murdered on Thornton Heath. Telesford’s 18-year-old killer was acquitted on the grounds that Telesford may have died from a consensual sex game that went wrong or may have inflicted the fatal injuries herself (since she was strangled with a scarf, how she would have managed this is unclear). As Jacques points out in Trans, the Sun headline, ‘Trannie killed in sex mix up’, anticipates the ‘transsexual panic’ defence which argues that if a trans person fails to disclose before the sexual encounter, she is accountable for whatever happens next. Murder, this suggests, is the logical response to an unexpected transsexual revelation. ‘Those points,’ Jacques writes, ‘where men are attracted to us when we “pass” and then repulsed when we don’t are the most terrifying … all bets are off.’ ‘She had hoped to avoid the worst possibilities of her new life,’ the narrator of Roz Kaveney’s novel Tiny Pieces of Skull observes after a particularly ugly encounter between the main transsexual character, Annabelle, and a policeman with a knife. (The novel, written in the 1980s but only published last year, is based on Kaveney’s post-transition life in Chicago in the 1970s.) In fact, whatever may have been said in court, we have no way of knowing whether Telesford’s killer was aware that she was trans, whether her identity was in some way ambiguous, whether – as with Corbett – this may indeed have been the lure. Either way, ‘transsexual panic’ suggests that confrontation with a trans woman is something that the average man on the street can’t be expected to survive. Damage to him outweighs, nullifies, her death. Not to speak of the unspoken assumption that thwarting an aroused man whatever the reason is a mortal offence.

That Telesford was a woman of colour is also crucial. If the number of trans people who are murdered is disproportionate, trans people of colour constitute by far the largest subset – the seven trans women murdered in the US in the first seven weeks of 2015 were all women of colour. Today, those fighting for trans freedom are increasingly keen to address this racial factor (like the feminists before them who also ignored it at first) – in the name of social justice and equality, but also because placing trans in the wider picture can help challenge the assumption that transsexuality is an isolated phenomenon, beyond human endurance in and of itself. It is a paradox of the transsexual bid for emancipation that the more visible trans people become, the more they seem to excite, as well as greater acceptance, a peculiarly murderous hatred. ‘I know people have to learn about other people’s lives in order to become more tolerant,’ Jayne County writes in Man Enough to Be a Woman (one of Jacques’s main inspirations), but ‘sometimes that makes bigotry worse. The more straight people know about us, the more they have to hate.’

Feminists have always had to confront the violence they expose, and – in exposing – provoke, but when a transsexual person is involved, the gap between progressive moment and crushing payback seems even shorter. County exposes the myth, one of liberalism’s most potent, that knowing – finding oneself face to face with something or someone outside one’s usual frame of reference – is the first step on the path to understanding. What distinguishes the transsexual woman or man, the psychoanalyst Patricia Gherovici writes in Please Select Your Gender, her study of transsexual patients, is that ‘the almost infinite distance between one face and the other will be crossed by one single person’. Perhaps this is the real scandal. Not crossing the line of gender – although that is scandal enough – but blurring psychic boundaries, placing in such intimate proximity parts of the mind which non-trans people have the luxury of believing they can safely keep apart.

Trans is not one thing. In the public mind crossing over – the Caitlyn Jenner option – is the most familiar version, but there are as many trans people who do not choose this path. In addition to ‘transition’ (‘A to B’) and ‘transitional’ (‘between A and B’), trans can also mean ‘A as well as B’ or ‘neither A nor B’ – that’s to say, ‘transcending’, as in ‘above’, or ‘in a different realm from’, both. Thus Jan Morris in Conundrum in 1974: ‘There is neither man nor woman … I shall transcend both.’ Even that is not all. If transsexuality is subsumed in the broader category of transgender, as it is for example in the Transgender Studies readers, then there would seem to be no limit; one of the greatest pleasures of falling outside the norm is the freedom to pile category upon category, as in Borges’s fantastic animal taxonomy which Foucault borrowed to open The Order of Things (no order to speak of), or the catechisms of the ‘Ithaca’ chapter in Ulysses, whose interminable lists doggedly outstrip the mind’s capacity to hold anything in its proper place. At a Binary Defiance workshop held at the 2015 True Colours Conference, an annual event for gay and transgender youth at the University of Connecticut, the following were listed on the blackboard: non-binary, gender queer, bigender, trigender, agender, intergender, pangender, neutrois, third gender, androgyne, two-spirit, self-coined, genderfluid. In 2011 the New York-based journal Psychoanalytic Dialogues brought out a special issue on transgender subjectivities. ‘In these pages,’ the psychoanalyst Virginia Goldner wrote in her editor’s note, ‘you will meet persons who could be characterised, and could recognise themselves, as one – or some – of the following: a girl and a boy, a girl in a boy, a boy who is a girl, a girl who is a boy dressed as a girl, a girl who has to be a boy to be a girl.’ We are dealing, Stryker explains, with ‘a heteroglossic outpouring of gender positions from which to speak’.

These are not, however, the versions of trans that make the news. At the end of her photo session with Annie Leibovitz, Jenner looked at the gold medal she had won as Bruce Jenner in the 1976 Olympic decathlon, and commented as ‘her eyes rimmed red and her voice grew soft’: ‘That was a good day. But the last couple of days were better.’ It’s as if – even allowing for the additional pathos injected by Buzz Bissinger, who wrote the famous piece on Jenner for Vanity Fair – the photographic session, rather than hormones or surgery, were the culmination of the process (though Leibovitz herself insists the photos were secondary to the project of helping Caitlyn to ‘emerge’). What happens, Jacques asks in relation to the whole genre of ‘before’ and ‘after’ transsexual photography, ‘once the cameras go away?’ Not for the first time, the still visual image – unlike the rolling camera of Keeping up with the Kardashians – finds itself under instruction to halt the world and, if only for a split second, make it seem safe (like the answer to a prayer). The non-transsexual viewer can then bask in the power to confer (or not confer) recognition on the newly claimed gender identity. The power is real (plaudits laced with cruelty). It is the premise – you are male or female – which is at fault. There has been much criticism of Jenner, often snide, for decking herself out in the most clichéd, extravagant trappings of femininity. But her desire would be meaningless were it not reciprocated by a whole feverish world racing to classify humans according to how neatly they can be pigeonholed into their gendered place. This is the coercive violence of gendering which, Stryker is not alone in pointing out, is the founding condition of human subjectivity. A form of knowledge which, as Garfinkel already described it in the 1960s, makes its way into the unconscious cultural lexicon ‘without even being noticed’ as ‘a matter of objective, institutionalised facts, i.e. moral facts’. Today this view is as pervasive as ever. Writing in the Evening Standard in January this year, Melanie McDonagh lamented the relative ease of ‘sex-change’ which she sees around her: ‘The boy-girl identity is what shapes us most … the most fundamental … the most basic aspect of our personhood.’ Her article is entitled ‘Changing sex is not to be done just on a whim’. A whim? She has obviously not spoken to any transsexual people or read a word they have written.

In her current TV series I Am Cait, Jenner is keen to extend a hand to transsexual women and men who don’t enjoy her material privileges. She has made a point of giving space to minority transsexuals such as Zeam Porter who face double discrimination as both black and trans, although it is Laverne Cox in Orange Is the New Black who has truly taken on the mantle of presenting to the world what it means to be a black, incarcerated, transsexual woman. Cox also insists that, even now she has the money, she won’t undergo surgery to feminise her face. Jenner’s facial surgery lasted ten hours and led to her one panic attack: ‘What did I just do? What did I just do to myself?’ But, despite her greater inclusivity, faced with Kate Bornstein exhorting her to ‘accept the freakdom’, Jenner seemed nonplussed (as one commentator pointed out, Bornstein used the word ‘freak’ six times in a three-minute interview). This was not a meeting of true minds, even though in the second series of I Am Cait Bornstein is given a more prominent role. Like Stryker, Bornstein believes it is the strangeness of being trans, the threat it poses to those who are looking on whether with or without sympathy, that’s the point. Compare the impeccable, Hollywood moodboarded images of Jenner broadcast across the world – ‘moodboarded’, the word used by the stylist on the shoot, refers to a collage of images used in production to get the right feel or flow – with the image of Stryker in 1994 welcoming monstrosity via an analogy between herself and Frankenstein: ‘The transsexual body is an unnatural body. It is the product of medical science. It is a technological construction. It is flesh torn apart and sewn together again in a shape other than that in which it was born.’ Stryker stood at the podium wearing what she calls ‘genderfuck drag’:

combat boots, threadbare Levi 501s over a black lace bodysuit, a shredded Transgender Nation T-shirt with the neck and sleeves cut out, a pink triangle, quartz crystal pendant, grunge metal jewellery, and a six inch long marlin hook dangling around my neck on a length of heavy stainless steel chain. I decorated the set by draping my black leather biker jacket over my chair at the panellists’ table. The jacket had handcuffs on the left shoulder, rainbow freedom rings on the right side lacings, and Queer Nation-style stickers reading SEX CHANGE, DYKE and FUCK YOUR TRANSPHOBIA plastered on the back.

She was – is – wholly serious. It is the myth of the natural, for all of us, which she has in her sights. This is her justly renowned, exhortatory moment, unsurpassed in anything else I have read:

Hearken unto me, fellow creatures. I who have dwelt in a form unmatched with my desire, I whose flesh has become an assemblage of incongruous anatomical parts, I who achieve the similitude of a natural body only through an unnatural process, I offer you this warning: the Nature you bedevil me with is a lie. Do not trust it to protect you from what I represent, for it is a fabrication that cloaks the groundlessness of the privilege you seek to maintain for yourself at my expense. You are as constructed as me; the same anarchic Womb has birthed us both. I call upon you to investigate your nature as I have been compelled to confront mine. I challenge you to risk abjection and flourish as well as have I. Heed my words, and you may well discover the seams and sutures in yourself.

For many post-operative transsexual people, the charge of bodily mutilation is a slur arising from pure prejudice. It’s true that without medical technology none of this would have been possible. It’s also the case that the need for, extent and pain of medical intervention puts a strain on the argument that the transsexual woman or man is simply returning to her or his naturally ordained place – with the surgeon as nature’s agent who restores what nature intended to be there in the first place. Kaveney’s medical transition, for example, lasted two years, involving 25 general anaesthetics, a ten-stone weight gain, thromboses, more than one major haemorrhage, fistula and infections. She barely survived, though none of this has stopped her from going on to lead one of the most effective campaigning lives as a transsexual woman. In 1931, Lili Elbe died after a third and failed operation to create an artificial womb (the film The Danish Girl sentimentally changes this to the prior operation to create a vagina so that she dies having fulfilled her dream). When I met April Ashley in Oxford in the early 1970s – she was in the midst of the legal hearing and Oxford was a kind of retreat – she expressed her sorrow that she would never be a mother. On this, female-to-male transsexuals have gone further. In 2007, Thomas Beatie, having retained his female reproductive organs on transition, gave birth to triplets through artificial insemination. They died, but he has since given birth to three children.

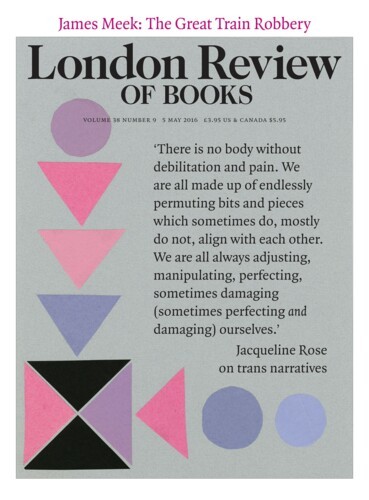

But for Stryker, mutilation is at once a badge of honour and a counter to the myth of nature in a pure state. There is no body without debilitation and pain. We are all made up of endlessly permuting bits and pieces which sometimes do, mostly do not, align with each other. We are all always adjusting, manipulating, perfecting, sometimes damaging (sometimes perfecting and damaging) ourselves. Today non-trans women, at the mercy of the cosmetic industry, increasingly submit to surgical intervention as a way of conforming to an image; failure makes them feel worthless (since nature is equated with youth, this also turns the natural process of ageing into some kind of aberration). ‘I’ve seen women mutilate themselves to try to meet that norm,’ says Melissa, mother of Skylar, who had top surgery with his parents’ permission at the age of 16. Shakespeare described man as a thing of ‘shreds and patches’, Freud as a ‘prosthetic God’, Donna Haraway as a cyborg. Rebarbative as it may at first seem, Stryker’s vision is the most inclusive. Enter my world: ‘I challenge you to risk abjection and flourish as well as have I.’ What you would most violently repudiate is an inherent and potentially creative part of the self.

The image of the trans world as an open church that includes all comers, all variants on the possibilities of sex, is therefore misleading. There are strong disagreements between those who see transition as a means, the only means, to true embodiment, and those who see transgenderism as upending all sexual categories. For the first, the aim is a bodily and psychic integrity that has been thwarted since birth: ‘Lili Elbe’s story,’ Niels Hoyer writes, ‘is above all a human story and each faltering step she takes is an awakening of her true self … [she] was willing to make the ultimate sacrifice to become the person within.’ (Hoyer is the editor of Elbe’s own notes and diaries, not to be confused with David Ebershoff, on whose ghastly novel The Danish Girl is based.) Jan Morris defines her transition as a journey on the path to identity: ‘I had reached Identity’; Ashley speaks of her desire ‘to be whole’, and her ‘great sense of purpose to make things right, make everything correct’; Chelsea Manning writes of ‘physically transitioning to the woman I have always been’. Such accounts seem to be the ones that most easily make it into the public eye, as if a shocked world can heave something like a collective sigh of relief (‘at least that much is clear, then’).

For those who, on the other hand, see transgenderism as a challenge to such clarity, the last thing it should do is claim to be the answer to its own question, or pretend that the world has been, could ever be, put to rights. This is simply a normative delusion, exacerbated by a neoliberal world order that offers itself as the only true dispensation and which now more or less covers the earth – rather like Scientology, of which Bornstein was a paid-up member in what we might call her formative years. Scientology, Bornstein tells us, ‘is supposed to erase all the pain and suffering you’ve ever felt in this and every other lifetime’. It is also a type of surveillance state which prohibits any kind of secrecy or privacy on the part of its members (unflinching eye-to-eye contact obligatory during any conversation), and which cast Bornstein into the wilderness as a ‘suppressive person’ as soon as her ambiguous sexuality was revealed. This despite the fact that, according to Scientology, each human contains a thetan, a spirit which – unlike in, say, Christianity – isn’t separate from the body but embedded within it. Crucially, thetans have no gender. Bornstein’s transsexuality is, therefore, indebted as much to Scientology (something she acknowledges) as it is her escape from it.

For Bornstein in her new life, as for Stryker, transsexuality is an infinite confusion of tongues. Neither of them is arriving anywhere. For Jay Prosser by contrast, the transsexual man or woman is enfolded in their new body like a second skin (his 1998 book, one of the most widely circulated and debated on the topic, has the title Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality). As he describes on the first page, two weeks after completing a course of massive testosterone treatment, he began living full-time as a man – ‘documents all changed to reflect a new, unambivalent status’. As it happens, Prosser is completely attuned to the ambiguities of sexual identity. He knows that transition, however real, is achieved at least partly by means of fiction, that it is through story-making that transsexual people arrive at the resolution they seek (hence the ‘body narratives’ of the title, narratives which in his analysis track the complexities of sexual being carried and enacted by these narratives). Partly because he is so immersed in psychoanalytic thinking, he understands how far sexual being – on the skin and in the bloodstream – reaches into the roots of who we are. Transition is testament to the fact, at once alterable and non-negotiable, of sexual difference: ‘In transsexual accounts,’ he writes, ‘transition does not shift the subject away from the embodiment of sexual difference but more fully into it.’ This is why, for some, transsexuality, or rather this version of transsexuality, is conservative, reinforcing the binary from which we all – trans and non-trans – suffer. Freud, for example, described the long and circuitous path to so-called normal femininity for the girl – originally bisexual, wildly energised by being all over the place – as nothing short of a catastrophe (admittedly, this isn’t the version of female sexuality for which he is best known).

Yet for Prosser, to move from A to B is a conclusive self-fashioning or it is nothing. In the special issue of Psychoanalytic Dialogues on transsexual subjectivities, Madeleine Suchet draws on Prosser in her analysis of Raphael, a female-to-male transsexual who explains: ‘Boy has to be written on the body’ – an idea she struggles to accept. She has to move from her original stance that sexual ambiguity should be sustainable without any need for bodily change (‘Crossing Over’, the title of her essay, refers as much to her journey as it does to his). Prosser talks of ‘restoration’ of the body. Note how ‘restoration’ chimes with the ‘born in the wrong body’ mantra which, while deeply felt by many trans people, is also the child of a medical profession which for a long time would accept nothing less as the basis for hormonal or surgical intervention. In the 1960s, the profiles of candidates for medical transition were found to be strangely in harmony with Harry Benjamin’s then definitive textbook on the subject: ‘strangely’, until it was realised that all of them had been reading it and brushing up their lines.

But if the longing is for restoration, arrival, the end of ambivalence, then the infinite variables of trans identity – which the Commons report Transgender Equality admits it cannot keep up with – are a bit of a scam, or at least a smokescreen covering over the materiality of a body in the throes of transition. A year after his book was published, Prosser wrote a palinode in which he criticised his own account of the body as pure matter, the irreducible ground of all that we are, and allowed much more space to the irreducible, even unspeakable agony of transition. But the living flesh of the argument remains, however scarred and traumatised. In a move whose rhetorical violence he was willing to acknowledge, Prosser suggested in Second Skins that endorsing the performativity of trans, or rather trans as performativity (that is, trans as something that exposes gender as a masquerade for all of us), verges on ‘critical perversity’. Judith Butler was the target, charged with celebrating as transgressive the hovering, unsettled condition, which, as Teleford, Jacques and Kaveney testify, places transsexual people at risk of violence. There is another distinction at work here, a division of labour between exhilaration and pain, brashness and dread, pleasure or danger. Or to put it another way, according to this logic, ‘queers can’t die and transsexuals can’t laugh’ – a formula lifted from a commentary on the work of the trans cabaret artist Nina Arsenault, who, while modelling herself on a Barbie doll, manages to cover all the options by performing herself as both real and fake. There are no lengths to which Arsenault has not gone, no procedures she hasn’t suffered, to craft herself as a woman, but she has done this, not so much in order to embody femininity as to expose it, to push it right over the edge. Hence her parody of Pamela Anderson (who is of course already a parody of herself): an ‘imitation of an imitation of an idea of a woman. An image which has never existed in nature.’

The question of embodiment therefore brings another with it. Does the transsexual woman or man, in her or his new identity, count as real? I am genuinely baffled how anyone can believe themselves qualified to legislate on the reality, or not, of anyone else, without claiming divine authority (or worse). ‘Once you decide that some people’s lives are not real,’ Kaveney wrote, ‘it becomes okay to abuse them.’ Nonetheless, in 1979 Janice Raymond pronounced in The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male that male-to-female transsexuals are frauds (on this issue, female-to-male seem to pose less of a problem even though surgical transition is much harder in their case, as phalloplasty is rarely a complete success) and should therefore be excluded from women-only spaces, since these are spaces which feminists have struggled, after centuries of male oppression, to create for themselves. In today’s parlance, Raymond was the first TERF, or ‘trans-exclusionary radical feminist’ (the term used by some trans people and by those feminists who oppose her position). For Raymond, male-to-female transsexuals are patriarchy writ large, the worst embodiments of a phallic power willing to resort to just about anything to fulfil itself – hence ‘transsexual empire’. Although I am sure this was not the intention, I have always found this argument extremely helpful in explaining to students the difference, indeed the gulf, between phallus and penis since, according to this logic, the authority and stature of the former would seem to require the surgical removal of the latter.

Raymond hasn’t been without influence. In 1980 she was commissioned by the US National Centre for Healthcare Technology to write a paper on the social and ethical aspects of transsexual surgery, which was followed by the elimination of federal and state aid for indigent and imprisoned transsexual women and men (Raymond has denied her paper played any part in the decision). A year later, Medicare stopped covering sex-reassignment, a decision only overturned in May 2014. That didn’t stop the South Dakota State Senate from passing a bill in February requiring transgender students to use locker rooms and toilets that correspond to their birth-assigned gender, on the grounds that male-to-female transsexuals sneaking into women’s toilets were a danger to women (similar legislation has been proposed in Texas, Arizona and Florida). This completely ignores the fact that it is the trans woman forced to use men’s toilets and locker rooms who is likely to be subject to sexual assault.

Germaine Greer is perhaps the best-known advocate of this position, or a version of it. She famously described male-to-female transsexuals as ‘pantomime dames’, had to resign as a fellow of Newnham College, Cambridge more or less as a consequence (after opposing the appointment of transgender Rachel Padman to a fellowship), and is now the object of a no-platform campaign. ‘What they are saying,’ Greer responded when the issue arose again in November 2015, ‘is that because I don’t think surgery will turn a man into a woman I should not be allowed to speak anywhere.’ She is being disingenuous. This is Greer in 1989 (the quotation courtesy of Paris Lees, one of the most vocal trans activists in the UK today):

On the day that The Female Eunuch was issued in America, a person in flapping draperies rushed up to me and grabbed my hand. ‘Thank you so much for all you’ve done for us girls!’ I smirked and nodded and stepped backwards, trying to extricate my hand from the enormous, knuckly, hairy, beringed paw that clutched it … Against the bony ribs that could be counted through its flimsy scarf dress swung a polished steel women’s liberation emblem. I should have said: ‘You’re a man. The Female Eunuch has done less than nothing for you. Piss off.’ The transvestite held me in a rapist’s grip.

‘All transsexuals,’ Raymond stated, ‘rape women’s bodies by reducing the real female form to an artefact.’ With the exception of incitement, of which this could be read as an instance, I tend to be opposed to no-platforming: better to have the worst that can be said out in the open in order to take it down. I also owe Greer a personal debt. Hearing her as an undergraduate in Oxford in 1970 was a key moment in setting me on the path of feminism. But reading this, I am pretty sure that, were I transsexual, I wouldn’t want Greer on any platform of mine.

Apart from being hateful, Raymond, Greer and their ilk show the scantest respect for what many trans people have had to say on this topic. However fervently desired, however much the fulfilment of a hitherto thwarted destiny, transition rarely seems to give the transsexual woman or man unassailable confidence in who they are (and not just because of the risk of ‘detection and ruin’). Rather, it would seem from their own comments that the process opens up a question about sexual being to which it is more often than not impossible to offer a definitive reply. This is of course true for all human subjects. The bar of sexual difference is ruthless but that doesn’t mean that those who believe they subscribe to its law have any more idea of what is going on beneath the surface than the one who submits less willingly. For psychoanalysis, it is axiomatic, however clear you are in your own mind about being a man or a woman, that the unconscious knows better. Given a primary, universal bisexuality, sex, Freud said, is an act involving at least four people. The ‘cis’ – i.e. non-trans – woman or man is a decoy, the outcome of multiple repressions whose unlived stories surface nightly in our dreams. From the Latin root meaning ‘on this side of’ as opposed to ‘across from’, ‘cis’ is generally conflated with normativity, implying ‘comfortable in your skin’, as if that were the beginning and end of the matter.

Who, exactly, we may therefore ask – trans or non-trans – is fooling whom? Who do you think you are? – the question anyone hostile to transsexual people should surely be asking themselves. So-called normality can be the cover for a multitude of ‘sins’. The psychoanalyst Adam Limentani described the case of an apparently perfectly heterosexual ‘vagina man’ who during intercourse fantasised that he was himself being penetrated, which meant that to have sex was to be unfaithful to himself (he was fucking another woman), and that he could never, psychically, be father to his own child – whose child would it be? Women can share the same syndrome: a fantasy that their vagina is not really their own but belongs to somebody else, although, since they appear to be ‘normal,’ no one would ever guess. Even with the apparently straightest man or woman, there is no telling.

This is a selection of quotes from transsexual narratives, suggesting that as often as not the authors both know and don’t know who they are, or even – in some cases – who precisely they want to be:

Some transsexuals are no happier after surgery, and there are many suicides. Their dream is to become a normal man or woman. This is not possible, can never be possible, through surgery. Transsexuals should not delude themselves on this score. If they do, they are setting themselves up for a big, possibly lethal, disappointment. It is important that they learn to understand themselves as transsexuals.

April Ashley, The First Lady

The trans prefix implies that one moves across from one sex to another. That is impossible … I was not reared as a boy or as a young man. My experience can include neither normal heterosexual relations with a woman nor fatherhood. I have not shared the psychological experience of being a woman or the physical one of being a man.

Mark Rees, Dear Sir or Madam

‘I live as a woman every day.’

‘Do you consider yourself to be a woman?’

‘I consider … Yes, yes, but I know what I – I know what I am … I do everything like a woman. I act like a woman, I move like a woman … I know I’m gay and I know I’m a man.’

Anita, a Puerto Rican transgender sex worker interviewed by David Valentine in Imagining Transgender

My body can’t do that [give birth]; I can’t even bleed without a wound, and yet I claim to be a woman … I can never be a woman like other women, but I could never be a man.

Susan Stryker, ‘My Words to Victor Frankenstein’

I certainly wouldn’t be happy with the idea of being a man, and I don’t consider myself a man, but I’m not going to try and convince anyone that I’m really a woman.

Jayne County, Man Enough to be a Woman

It had been such a relief for me when I could stop pretending to be a man. Well, it was a similar relief not to have to pretend that I was a woman … I was now a lesbian with a boyfriend, but I wasn’t a real lesbian and he wasn’t a real boy … no matter what I bought – I’d look in the mirror and see myself as a man in a dress. Sure, I knew I wasn’t a man. But I also knew I wasn’t a woman.

Kate Bornstein, Queer and Pleasant Danger

I have a male and female side … I don’t know how they relate … [I] had to ask myself: how trans did I want to be?

Juliet Jacques, Trans

As the oestrogen started to change her body, Jacques felt for the first time ‘unburdened by that disconnect between body and mind.’ She even wondered whether one day the original disconnect might be ‘hard to recall’. But this didn’t stop her in the same moment asking: ‘What kind of woman have I become?’ Soft-spoken and deep-voiced, understated and urgent, Jacques comes across as a woman carrying an ambiguity she doesn’t seem to want or feel able fully to shed. She is also as keen to talk about Norwich City Football Club and the underground music and counter-culture scene as she is to tell her tale of transition – why is it assumed that transition is all transsexual people have to talk about? No performance (except to the extent that anyone appearing in public is of necessity performing); no exhilaration (she is one of the few transsexual people I have read or heard willing to explore her own depression); no definitive arrival anywhere. Affirmed and subdued by her own experience, she confounds the distinction, not just between male and female, but also between the emotional atmospheres which the various trans identities are meant – ‘instructed’ may be the right word – to personify. On this matter, the argument, the insistence on playing it one way or the other, can be virulent.

The statements I quoted are not uncontroversial. Bornstein has been labelled ‘transphobic’ and picketed by some in the trans community for refusing to identify as either man or woman, and for her stance on the issue of women-only spaces: ‘I thought every private space has the right to admit whomever they want – I told them … it was their responsibility to define the word woman. And I told the trans women to stop acting like men with a sense of entitlement.’ ‘I give great soundbites when it’s about sex,’ she apologises to a furious Riki Anne Wilchins who had invited her to speak, ‘but I always fuck up politics.’ In a wondrous twist, Paris Lees credits Germaine Greer with guiding her to insight on this matter:

Greer caused me to question my identity, and form a more complex one. She was right: I am not a woman in the way my mother is; I haven’t experienced female childhood; I don’t menstruate. I won’t give birth. Yes, I have no idea what it feels like to be another woman – but nor do I know what it feels like to be another man. How can anyone know what it feels like to be anyone but themselves?

Not all trans people take this position. At the In Conversation with the Women’s Liberation Movement conference, held in London in October 2013, I sat behind two trans women who objected when the historian Sue O’Sullivan described how 1970s feminism had allowed young women for the first time to explore their own vagina, to claim it as intimate companion. Her account was seen by them as transphobic for excluding trans women who most likely will not have had that experience in their youth but who are ‘no less women’ for that (there are trans women for whom, on similar grounds, the word ‘vagina’ or ‘vulva’ shouldn’t ever be used). But this is not the whole story – or even half of it. I would say it is because of the journey they have made, and because so many of them have suffered such pain in prising open the question ‘Who is a real woman?’ that transgender women should be listened to. And not just because it is so manifestly self-defeating for feminism and trans, two movements fighting oppression, not to talk to each other.

A further reason why trans and feminism should be natural bedfellows is that male-to-female transsexuals expose, and then reject, masculinity in its darkest guise. This side of the argument is missed by Greer et al, who tend to overlook the fact that if you want more than anything in the world to become a woman, then chances are there is somewhere a man who, just as passionately, you do not want to be. ‘I stopped my life living as a man,’ Bornstein writes of her father in the prologue to A Queer and Pleasant Danger, ‘in large part because I never wanted to be a man like him’ (coming to terms with his ghost is one of her motives in writing the memoir). One of Nina Arsenault’s earliest memories is of boys knifing magazine images of women: ‘I know that this is exactly what I will be when I grow up.’

In the first half of Conundrum, Morris offers the reader a paean to maleness: the feeling of being a man ‘springs … specifically from the body’, a body which, ‘when it is working properly’, she recalls, is ‘a marvellous thing to inhabit … Nothing sags in him’ (never?). But this selfsame masculinity, epitomised by an assault on Everest timed to coincide with the queen’s coronation, is ‘snatching at air’, a ‘nothingness’, that leaves Morris dissatisfied – ‘as I think,’ she concludes, ‘it would leave most women’. ‘Even now I dislike that emptiness at its climax, that perfect uselessness’ (as good a diagnosis of the vacuity of phallic power as you might hope to find). If you are a man, you can spend a lifetime striving for this version of masculinity, never to discover the emptiness and fraudulence at its core. Somewhere Morris is, or rather was, an upper-class English gent imbued with the values of his sex and class – the family on his mother’s side descends from ‘modest English squires’. When Morris sheds maleness, it is therefore a patriotic, militarist identity, with its accompanying imperial prejudice, that is, at least in part, discarded: ‘I still would not want to be ruled by Africans, but then they did not want to rule me’ (though even this does not quite make it to the question of who Africans might want, and not want, to be ruled by). This legacy is hard to relinquish. Released from ‘my own last remnants of maleness’, she returns from Morocco where she underwent her transition, ‘like a princess emancipated from her degrading disguise, or something new out of Africa’. Morris was operated on by Georges Burou, the surgeon who had operated on Ashley in 1960 and one of the first to undertake the procedure. By 1972, the operation was available in the UK, but Morris chose to go abroad when it was made a legal condition that before having surgery she divorce her wife with whom she had fathered five children.

The issue of masculinity is in some ways more present for female-to-male transsexuals. In Nebraska in 1993, female-to-male transsexual Brandon Teena was murdered along with two others (the story was the basis for the 1999 film Boys Don’t Cry). After the murders, it became a matter of debate whether Teena should be seen as a female-to-male transsexual without access to sex reassignment surgery or a transgender butch who had chosen not to transition. We will never know. What we do know is that he was raped shortly before he was murdered by a group of local boys in one sense intent on returning him to the body which in their eyes he denied, in another enraged at the success he was having with local girls. ‘This case itself hinges on the production of a “counterfeit” masculinity,’ Jack Halberstam writes in his in-depth analysis of Teena’s murder in In a Queer Time and Place, ‘that even though it depends on deceit and illegality, turns out to be more compelling, seductive and convincing than the so-called real masculinities with which it competes.’ For this reason, he continues, ‘the contradiction of his body … signified no obstacle at all as far as Brandon’s girlfriends were concerned.’ Indeed it may have been the draw. In the small-town rural America where Teena lived, male crime passed effortlessly down the generations. ‘You keep seeing the same faces,’ Judge Robert Finn told John Gregory Dunne, who wrote about the case in 1997. ‘I’m into third-generation domestic abuse and restraining orders.’ He was talking about husbands and lovers whose fathers and grandfathers had appeared before him on the same charges in the course of his 16 years on the bench. Teena offered the girls ‘sex without pregnancy or fisticuffs’. Skylar decided not to go for genital reconstruction, not feeling the need to be, in his words, ‘macho bro’.

What are you letting yourself in for if you choose to become a man? What is the deal? At a key stage of his transition, Raphael, the female-to-male transsexual who believes ‘boy has to be written on the body’, said to his analyst: ‘If I want them to treat me like a guy, I have to be a guy.’

‘He is quiet. We are both quiet,’ Suchet observes. ‘There is a growing sense of unease in the space between us. I sense my body tensing up. Who am I going to end up sitting in the room with?’

‘You really think you have to be a misogynist to be recognised as a guy?’ she asks him.

‘I am afraid I am going to become a complete asshole,’ Raphael replies. ‘What if I am this sexist bastard?’

It turns out that it is only as a man that Raphael can allow himself a form of passivity and surrender that was too dangerous for him as a girl. Over the years the analysis uncovers that as a female child he had been the receptacle of vicious maternal projections and may have been abused by his mother. Becoming a man allows him, among other things, to become the girl who, as long as he was lodged in a female body, he could never dare to be. ‘I want my body to say: “Here this is Raphael. He’s a guy, but he’s not only a guy. He’s a female guy, who sometimes wants to be able to be a girl.”’ (Raphael is the patient Virginia Goldner describes as ‘the girl who has to be a boy to be a girl’.)

Raphael doesn’t welcome the link Suchet proposes between his being transsexual and his childhood abuse and complains that she delegitimises and invalidates his experience by analysing it as the disturbed outcome of a traumatic past (although, as should not need stating, trauma is not pathology but history). He isn’t alone in making this case. Although the incidence of mental disturbance among transsexual people is no greater than among the population at large, transsexual people have to fight the stigma of psychopathology, not least because any sign of it during medical consultation is likely to disqualify them from surgery, where the only narrative that passes is the one that confidently asserts that they have always known who they really are. In 1980, transsexuality (adults) and Gender Identity Disorder (children) entered the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSMIII) – homosexuality had been officially removed from the registry in 1973. The struggle to have these categories dropped in turn, precisely as delegitimising, then runs up against the problem of seeming to imply that all other disorders in the manual legitimately belong there. Gender Identity Disorder was subsequently replaced with Gender Dysphoria, intended to be less pathologising (being included in the manual has the ‘advantage’ of allowing some insurance companies to cover the transition process).

In Imagining Transgender, one of David Valentine’s key informants, Cindy, suffers from depression. ‘Her history of child abuse, rape, drug addiction, alcoholism, suppression of feelings,’ he writes, ‘is one that is all too common among transgender-identified people.’ And among many non-trans people (the class issue here is glaring). It’s the link, balance or causal relation between inner distress and the world’s cruelty that is so hard, and sometimes impossible, to gauge. ‘How,’ Goldner asks, ‘are we to distinguish “psychodynamic” suffering from the transphobic “cultural suffering” caused by stigma, fear, hatred?’ ‘I know,’ Jacques writes, ‘there will be difficulties, both with things inside my head, and with intolerant people in the outside world.’ In response to this ambiguity, and to the misuse of intimate, personal history to run the transsexual person to ground, some argue that aetiology or the search for causes should simply be dropped. ‘[When] it comes to the origin of sexual identity,’ the New York psychoanalyst Ken Corbett (no relation to Arthur) wrote in 1997, ‘I am willing to live with not knowing. Indeed, I believe in not knowing … [I am not interested in] the ill-conceived aetiological question of “Why” [someone is homosexual], I am interested in how someone is homosexual.’

For me this is a false alternative. Why, in an ideal world (not that we are living in one), should the ethical question of how we live be severed from knowledge of how we have come to be who we are? What, we might ask instead, is the psychic repertoire, the available register of admissible feelings, for the oppressed and ostracised? It is a paradox of political emancipation, which the struggle for trans freedom brings starkly into focus, that oppression must be met with self-affirmation, as in: ‘I have dignity. You will not overlook me.’ To vacillate is political death. No second thoughts. No room for doubt or the day-to-day aberrations of being human. At moments, reading trans narratives, I have felt the range of utterances the trans person is permitted narrow into a stranglehold: ‘I am discriminated against.’ ‘I suffer.’ ‘I am perfectly fine.’ ‘There is nothing wrong with me.’ I think this might be the reason I often get the sense of a psychic beat missed, of there being parts of the story which do, and don’t, want to be told, moments that reach the surface, only to be forgotten or brushed aside in the forward march of narrative time. As though the personal could also be a front for the personal, covering over what it ostensibly, even generously displays (or as Jacques puts it in relation to ‘before’ and ‘after’ photographs, having ‘the strange effect of masking the process of change as they appear to reveal it’). Mark Rees was one of girl twins, registered as a girl at birth: his twin sister died five days later and his parents tried to hide their disappointment when three years later another girl was born – they had wanted a boy – who then turned out, compared with Mark, to be the ‘perfect’ female child. A male-to-female transsexual who prefers not to be named was identified as dyspraxic as a young male child, born to a mother who had earlier suffered an ectopic pregnancy and who subsequently gave birth to a girl child with no trace of disability who at last fulfilled the parents’ dreams. There can be no ‘wild’ analysis of these histories, but it is hard not to see the shadow of death and an intolerable burden of idealisation fall, along the rigid axis of sexual difference, on these young bodies and minds. These moments are coercive, but given their due place, they also increase the options for understanding. They show transsexuality, like all psychic identities, as an exit strategy as much as a journey home.

There is rage against the original body in many of these stories, especially in the male-to-female narratives I have read. April Ashley, Mark Rees, Juliet Jacques all write of the hatred, revulsion, abhorrence (their words) with which they viewed their male genitals before surgery. Jacques: ‘I just want this fucking thing off my body right now.’ Weeks after her surgery, she wakes up to the ‘horrific realisation’ that ‘It’s still there!’ before remembering that transsexual women who underwent surgery before her had warned her that this is the dream. ‘Other forces,’ Lili Elbe wrote in her memoir, ‘began to stir in my brain and to choke whatever remnant of Andreas [Einer Wegener] still remained there … Andreas has been obliterated in me – is dead.’ The pre-surgical body is, it seems, ungrievable (Judith Butler speaks of ‘ungrievable’ lives, referring to the dead bodies of the enemy in wartime that do not count or matter). But without some recognition of how deep the stakes, how driven the impulse, the story is hard to fathom and risks being delivered straight into the arms of a crazy narrative, beyond all human understanding. Nor do such insights necessarily undermine the more straightforward tale of a mistake being at last redressed. They are rarely to be found in each other’s company, but no one gains by believing that the two forms of understanding are unable to tolerate each other.

In saying this, realise I am repeating, in psychoanalytic terms, the call made by Sandy Stone as early as 1987, in her reply to Janice Raymond, ‘The Empire Strikes Back: A Post-transsexual Manifesto’, in which she writes about having been personally attacked for working at an all-woman music collective. The process of ‘constructing a plausible history’, in other words ‘learning to lie effectively about one’s past’, Stone wrote, was blocking the ability of trans people to represent the full ‘complexities and ambiguities of lived experience’. The one thing Dean Spade learns from counselling sessions, is that ‘in order to be deemed real, I need to want to pass as male all the time, and not feel ambivalent about this.’ ‘We have foreclosed the possibility of analysing desire and motivational complexity in a manner which adequately describes the multiple contradictions of individual lived experience,’ Stone warned. ‘Plausible’ is the problem. It obliges the trans person, whatever the complexity of their experience, to hold fast to the rails of identity. It turns the demand to take control of one’s own life, which is and has to be politically non-negotiable, into a vision of the mind as subordinate to the will (the opposite of what the psychic life can ever be). And it leaves no room for sexuality as the disruptive, excessive reality and experience it mostly is. I have been struck at how little space for sex many of these accounts, before and after, seem to offer. Bornstein is one exception (she always pushes the boat out). In discussion with Paris Lees in London in February this year, her refrain, first spoken loud and clear and then muttered more or less throughout the exchange, was ‘sex, sex, sex’. In A Queer and Pleasant Danger, she invites her readers, should they be so inclined, to skip several pages near the end of the book where she recounts an intense, in the end personally self-defeating, sado-masochistic interlude. Bornstein herself makes the link back to the operating table. In the prologue, she describes cutting a valentine’s heart above her heart as one way of dealing with searing pain. Once one barrier falls, then, if you choose not to keep the lid on, so, potentially at least, do all the rest.

Today trans is everywhere. Not just the most photogenic instances such as Bruce Jenner and Laverne Cox, or The Danish Girl at a cinema near you, or the special August 2015 issue of Vanity Fair on ‘Trans America’ (co-edited by GQ, the New Yorker, Vogue and Glamour), from which a number of my stories are taken; but also, for instance, the somewhat unlikely, sympathetic front-page spread of the Sun in January 2015 on the British Army’s only transgender officer (‘an officer and a gentlewoman’), plus the Netflix series Transparent, Bethany Black, Doctor Who’s first trans actress, EastEnders’s Riley Carter Millington, the first trans actor in a mainstream UK soap opera, and Rebecca Root of Boy Meets Girl, the first trans star of a British TV show; or again reports of the first trans adopters and foster carers, or the 100 per cent surge in children seeking gender change, as shown in figures released by the Tavistock Clinic in November 2015. From 2009 to 2014, the number of cases referred to the Portman NHS Trust’s Gender Identity Service rose from 97 to 697.

Transgender children in the UK today have the option of delaying puberty by taking hormone blockers; they can take cross-sex hormones from 16 and opt for sex reassignment surgery from the age of 18. Cassie Wilson’s daughter Melanie announced he was Tom at the age of two and a half (now five, he has annual appointments at the Tavistock); Callum King decided she was Julia as soon as she could talk. In 2014, the mental health charity Pace surveyed 2000 young people who were questioning their gender: 48 per cent had attempted suicide and 58 per cent self-harmed. ‘They kill themselves,’ Julia’s mother commented: ‘I want a happy daughter, not a dead son.’ Julia gives herself more room for manoeuvre and defines herself as ‘both’. She likes to ask her girlfriends at school if they would like to be a boy for a day just to see what it would feel like and, whatever they answer, she retorts: ‘I don’t have to because I’m both.’

It would seem, then, that the desire for transition comes as much, or more, from the parent and adults than from the child. One mother in San Francisco was told by the school principal that her son should choose one gender or the other because he was being harassed at school. He could either jettison his pink Crocs and cut his long blond hair, or socially transition and come to school as a girl – he’d abandoned the dresses he used to like wearing and had never had any trouble calling himself a boy. She was wary: ‘It can be difficult for people to accept a child who is in a place of ambiguity.’ At a conference in Philadelphia attended by Margaret Talbot, the journalist who wrote about Skylar, one woman admitted that she was the one who needed to know: ‘We want to know – are you trans or not?’ ‘Very little information in the public domain talks about the normality of gender questioning and gender role exploration,’ Walter Meyer, a child psychologist and endocrinologist in Texas, remarks. ‘It may be hard to live with the ambiguity, but just watch and wait.’ ‘How,’ Polly Carmichael of the Tavistock asks, ‘do we keep in mind a diversity of outcomes?’ What desire is being laid on a child who is expected to resolve the question of transition? On whose behalf? Better transition over and done with, it seems, than adults having to acknowledge, remember, relive, the sexual uncertainty of who we all are.

The increase in the number of trans children may be a striking, and for some shocking, new development. But transgenderism is not new. Far from being a modern-day invention, it may be more like a return of the repressed, as humans slowly make their way back, after a long and cruel detour, to where they were meant to be. One of my friends, when she heard I was writing on the topic, said we should all hang on in there, as the ageing body leads everyone to transition in the end anyway. (I told her she had somewhat missed the point.) The Talmud, for example, lists six genders (though Deuteronomy 22.5 thunders against cross-dressing). ‘Strange country this,’ Leslie Feinberg quotes a white man arriving in the New World in 1850, ‘where males assume the dress and duties of females, while women turn men and mate with their own sex.’ Colonialists referred to these men and women as berdache, and set wild dogs on them, in many cases torturing and burning them. In pre-capitalist societies, before conquest and exploitation, Feinberg argues, transgender people were honoured and revered. Feinberg’s essay, ‘Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come’, first published in 1992, called for a pangender umbrella to cover all sexual minorities. It was the beginning of a movement. The first Transgender Studies Reader stretches back into the medical archive then forward into the 1990s: the activism of that decade was the ground and precondition of the engagement, the defiance, the manifestos which, in the face of a blind and/or hostile world, the Reader offered. These volumes are vast, they contain multitudes, as if to state: ‘Look how many we are and how much we have to say.’ We need to remember that these bold and unprecedented interventions predated by more than two or even three decades, the phenomenon known as ‘trans’ in popular culture today.

At the end of his foreword to the first Transgender Studies Reader, Stephen Whittle lists as one of the new possibilities for trans people opened up by critical thought the right to claim a ‘unique position of suffering’. But, as with all political movements, and especially any grounded in identity politics, there is always a danger that suffering will become competitive, a prize possession and goal in itself. The example of the berdache, or of Brendon Teena caught in a cycle of deprivation, shows, however, that trans can never be – without travestying itself and the world – its own sole reference point. However distinct a form of being and belonging, it has affiliations that stretch back in time and across the globe. I have mainly focused on stories from the US and UK, but transgender is as much an issue in Tehran, where trans people have had to fight against being co-opted into an anti-Islam argument that makes sexual progressivism an exclusive property of the West (in fact sex reassignment was legalised following a personal diktat from the Ayatollah Khomeini); and in India where the hijra – men who wear female clothing and who renounce sexual desire by undergoing sacrificial emasculation – are recognised and esteemed as a third sex.

Like any story of a person’s life, all the stories I have discussed are caught in histories not of their own choosing. They also need to be told. Ashley, for example, a child of the Second World War, finds herself in a circle that includes Goebbels’s sister-in-law, who inherited Goebbels’s wealth and property after he and his wife murdered their six children and then killed themselves. ‘I was to find,’ Ashley writes of their growing friendship, ‘that most people had secrets – some in their own way, as delicate as mine.’ The link between them goes deeper than she may have realised. Magnus Hirschfield, sexologist, founder of the first gay rights organisation and an early advocate for transgender people, was described by Hitler as ‘the most dangerous man in Germany’; the Nazis destroyed his institute and burned his research collection. The war is her story. Ashley’s mother, who hated her and would regularly pick her up by her ankles and bang her head on the floor, worked at the Fazakerley bomb factory, losing much of her hair and all her teeth from being around TNT. ‘As a child growing up during the Second World War,’ Ashley begins her memoir, ‘I was generally badly treated by everybody.’

Caitlyn Jenner says she will still vote Republican, even for Donald Trump, despite the party’s dire record on LGBT issues. She is being consistent. As Bruce, the famous athlete, Bizzinger recalls, she had been a weapon in the Cold War: ‘Mom and apple pie with a daub of vanilla ice cream for deliciousness in a country desperate for such an image.’ ‘He had beaten the Commie bastards. He was America.’ In an article in the New York Times in 1977, Tony Kornheiser described Jenner as ‘twirling the nation like a baton; he and his wife Chrystie are so high up on the pedestal of American heroism, it would take a crane to get them down.’ Who is to say that something of that dubious political aura has not made its way, like a lingering scent, into the phenomenon that is Caitlyn Jenner today?

For Jayne County being trans was a ticket to the other side, what she calls the ‘flaming side of gay life’. One of the most successful plays she wrote and performed, World: Birth of a Nation, included a scene where John Wayne gives birth to a baby out of his anus (not the way most people like to think of the birth of a nation, or indeed John Wayne). The Village Voice gave it a rave review. County was brought up in right-wing rural America where biblical prophecy ruled and the Beast took the shape of a United Europe with Germany at its head (Germans would apparently unite with the Arab nations against the Jews). She credits Bill Clinton with fostering an atmosphere in the 1990s that made the US ‘wide open for people of all variations of sexuality, including trannies of every shape, size and colour’. But already by the middle of the decade when County returned from the Berlin underground, the Conservative right were taking power, and the Democrats, with their liberal stand on abortion, gay rights and prayer in schools, were seen as disciples of Satan ‘by Baptist bastards, Republican retards and right-wing Christians’ (no change there then). ‘This,’ she asserts, ‘just makes me more defiant than ever. I’ll get more and more outrageous just to freak them out’ (she had been planning to retire to her home community, dress in more subdued fashion, and settle down). These are the last lines of her book. We do trans people no favours if we ignore these contexts. As if, after all, trans is merely a tale transsexuals are telling themselves, cut off and leading a strange life all their own (which must increase the voyeurism, the over-intense focus from which they suffer).

In 1998, the Remembering Our Dead project was founded in the US in response to the killing of Rita Hester, an African American trans woman who was found murdered in her Massachusetts apartment. By 2007, 378 murders had been registered, and the number continues to climb today. Commemoration is crucial but also risky. There is a danger, Sarah Lamble writes in the second Transgender Studies Reader, that ‘the very existence of transgender people is verified by their death’: that trans people come to define themselves as objects of violence over and above everything else (the violence that afflicts them usurping the identity they seek). ‘In this model,’ Lamble continues, ‘justice claims rest on proof that one group is not only most oppressed but also most innocent,’ which implies that trans people can never be implicated in the oppression of others. Apparently, the list of victims in the archives gives no information about age, race, class or circumstances, although the activists are mostly white and the victims almost invariably people of colour, so that when the images are juxtaposed, they reproduce one of the worst tropes of colonialism: whites as redeemers of the black dead. At the core of the remembrance ceremony, individuals step forward to speak in the name of the dead. What is going on here? What fetishisation – Lamble’s word – of death? What is left of these complex lives which, in failing fully to be told, fail fully to be honoured?

On the other hand, I would tentatively suggest that we are witnessing the first signs that the category of the transsexual might one day, as the ultimate act of emancipation, abolish itself. In ‘Women’s Time’ (1981), Julia Kristeva argued that feminists, and indeed the whole world, would enter a third stage in relation to sexual difference: after the demand for equal rights and then the celebration of femininity as other than the norm, a time will come when the distinction between woman and man will finally disappear, a metaphysical relic of a bygone age. In the second Transgender Studies Reader, Morgan Bassichis, Alexander Lee and Dean Spade call for a trans and queer movement which would set its sights above all on a neoliberal agenda that exacerbates inequality, consolidates state authority and increases the number of incarcerated people across the globe. Today, the official US response to the regular and fatal violence meted out to trans and queer people is hate-crimes legislation, tacked onto Defense Bills, which lengthens prison sentences and strengthens the hand of the local and federal law imposing them. In 2007, the Employment Non-Discrimination Bill was gutted of gender-identity protection. Bill Clinton – pace Jayne County – may have liberalised the sexual life of the nation, but it was on his watch that the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act limited aid and increased penalties for welfare recipients. Viewed in this light, Clinton becomes, like Cameron, a leader whose social liberalism, including on sexual matters, is what allows him to drive through brutally unjust economic policies with such baffling ease.

‘Critical trans resistance to unjust state power,’ Bassichis, Lee and Spade argue, ‘must tackle such problems as poverty, racism and incarceration if it is to do more than consolidate the legitimate citizenship status of the most privileged segments of trans populations.’ As soon as you talk about privilege, everything starts to look different. Bassichis, Lee and Spade call for trans and queer activists to become part of a movement, no longer geared only to sexual minorities but embracing the wider, and now seen as more radical, aim of abolishing prisons in the US. ‘We can no longer,’ they state, ‘allow our deaths to be the justification of so many other people’s deaths through policing, imprisonment and detention.’ Trans people can’t afford to be co-opted by discriminatory and death-dealing state power. The regular and casual police killings of black men on the streets of America comes immediately to mind as part of this larger frame in which, they are insisting, all progressive politics should be set.

Death must not be an excuse for more death. Obviously it is not for me to make this call on behalf of trans people. I have written this essay from the position of a so-called ‘cis’ woman, a category which I believe, as I hope is by this point clear, to be vulnerable to exposure and undoing. Today, trans people – men, women, neither, both – are taking the public stage more than ever before. In the words of a Time magazine cover story in June last year, trans is ‘America’s next civil rights frontier’. Perhaps, even though it doesn’t always look this way on the ground, trans activists will also – just – be in a position to advance what so often seems impossible: a political movement that tells it how it uniquely is, without separating one struggle for equality and human dignity from all the rest.

Among the texts consulted for this article:

The First Lady by April Ashley and Douglas Thompson (Blake, 2006, out of print)

Transgender Equality: First Report of Session 2015-16 by the House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee (January)

A Queer and Pleasant Danger: The True Story of a Nice Jewish Boy who Joins the Church of Scientology and Leaves Twelve Years Later to Become the Lovely Lady She Is Today by Kate Bornstein (Beacon, 258 pp., £11.30, July 2013, 978 0 8070 0183 7)

Dear Sir or Madam by Mark Rees (Mallard, £8, Kindle edition)

Trans: A Memoir by Juliet Jacques (Verso, 330 pp., £16.99, September 2015, 978 1 7847 8164 4)

The Transgender Studies Reader, edited by Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle (Routledge, 752 pp., £41.99, 2006, 978 0 415 94709 1)

The Transgender Studies Reader 2, edited by Susan Stryker and Aren Aizura (Routledge, 693 pp., £46.99, March 2013, 978 0 415 51773 7)