I cycled to the Design Museum on my secondhand Carlton: a ten-speed club racer built in Worksop, Nottinghamshire in 1979 and later outfitted (plastic mudguards, ugly rack, slightly chunky tyres) as a light touring bike and ideal commuter. It is pretty much the bicycle I wanted when I was 14 – you might guess: it’s bright red – but then I ended up with a bottom-of-the-range blue Viking, knocked together in Northern Ireland out of heavy ‘gas pipe’ tubing, as the proper bike nerds like to say. I bought the Carlton cheap last year, hoping it was the sort of thing you could leave around the decayed Kent resort where I live. It seemed unstealable compared with local mountain bikes and the fixed-gear machines of Margate’s DFL crowd. I’m a little worried though: my students in London approve of the Carlton, and vintage racers are starting to look like this year’s fixies. I recently bought a lock for half the price of the bike.

Cycle Revolution is an exhibition devoted to ‘extraordinary bicycles and the people that ride them’ (until 30 June). It is divided into four categories, none of which quite fits me: a practically minded transport cyclist with, even so, a bike fetish some way beyond my financial means, let alone athletic ability. Which likely describes most of the exhibition’s visitors. The cycling ‘tribes’ in question – High Performers, Thrill Seekers, Urban Riders and Cargo Bikers – seem oddly pitched and even divisive, given the show’s wider remit to say something timely about the cycling renaissance of recent years and the attendant problems of urban design that it’s put into stark relief. At the same time, this is an exhibition about actual bike design: the engineering and aesthetic innovations that have altered but not fundamentally transformed the diamond-frame ‘safety’ bicycle of the late 19th century. And although that ambition too ends up compromised, for reasons I’ll give, there are some ravishing machines to stare at, if that is your thing.

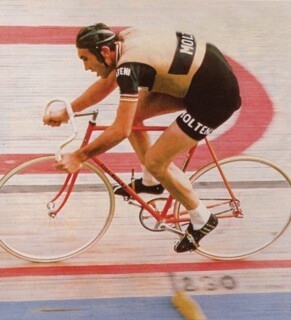

The exhibition deals rather swiftly with the High Performers (road and velodrome racers) and the Thrill Seekers (mountain bikers, BMX acrobats). There are carbon-fibre bikes ridden by the likes of Bradley Wiggins and Chris Boardman, recent and historical footage of the Tour de France, vitrines containing cutaway sections of aerodynamic frames and the spokeless wheels of modern track bikes. Design-wise I must confess to finding most of this contemporary gear quite hideous when set alongside, for example, Eddy Merckx’s orange steel track bike from 1972. For all their stealthy looks and complexly arrived at simplicity, the new bikes seem to advertise their efficiency a touch too reflexively, like an ugly sports car or an overdesigned razor. The visual contradiction – it is shared with the modern mountain bike: a spring-heeled and bulbous monstrosity – manages to make the most advanced answers to problems of weight, strength and aerodynamics look inflated and baroque. Perhaps the curators of Cycle Revolution knew this when into a wall-mounted array of high-tech road bikes and indestructible BMX jobs they snuck Raleigh’s absurd Chopper: a slow but unstable toy that merely looked as if it was built for speed. (We’re meant to think fondly now of the Chopper, the Space Hopper of childhood bicycles, but I remember outpacing these things on a small-wheeled shopping bike.)

A text panel at the start of the exhibition introduces the four cycling tribes and their bikes, describing ‘a period of evolutionary change, with the four types of bicycle increasingly diverging in the way that they are designed and engineered’. In truth, however, contemporary road, track and mountain bikes have not departed dramatically from the kind of thing built in the 1880s. Materials and precise geometry may have changed, but not the basic structure. An 1888 Rover, introducing the exhibition’s urban cycling section, features a diamond frame with a more or less horizontal crossbar and a chain drive to the back wheel, which is the same size as the front. It turns out that the more extreme variations on this design belong not to the history of cycling as sport, but to the search for a more convenient transport bicycle. It is among the Urban Riders and Cargo Bikers that the really innovative or eccentric bikes appear.

Consider the history of the small-wheeled shopper. (Mine was a creamy pink, by the way; the lads on scarlet Choppers had me beat ragged there.) The show includes a small display of models made by Alex Moulton in the late 1950s: imagined bicycles whose monocoque aluminium fairings would protect the rider from British weather and add some aerodynamic pizzazz to the urban get-around. (One of these even bruits its modernity with a horizontal white lightning flash.) But Moulton’s real innovations were hiding under the bike’s Eagle-era sci-fi skirts: when it went into production in 1962, the bike had a low frame, small wheels and front and rear suspension.

Moulton’s was not the first attempt at a machine that was easily stored and built to ride as if you were stepping out for a stroll. There were tiny-wheelers in the 1890s, and the exhibition also features the Velocino: a sort of miniature and reversed penny farthing, commissioned by Mussolini as a people’s bike but never produced. The Moulton, however, is a direct precursor of today’s folding bikes and especially the ubiquitous Brompton, whose rickety looking prototype is also in the show. What such bikes demonstrate is an ambition on the part of their designers to make the bicycle disappear, to make it so seamless a part of daily life that it’s more a device than a vehicle. Oddly, it’s an ambition shared with makers of the most cumbersome-looking cargo bikes. At the Design Museum there are ancient heavy butcher’s-boy machines, Dutch bakfietsen with space for kids and groceries, contemporary workhorses that seem more like street furniture than covetable rides.

In their definitive book on the subject, Bicycle Design (MIT, £25.95), Tony Hadland and Hans-Erhard Lessing devote only a short appendix to the question of bicycle aesthetics, opining that ‘form follows function’ is an ethos even more justified when making a bicycle than a building. It’s true in a way: the bicycle is as it were all bicycle – that’s to say, it’s all engineering. And for who knows what reason the Design Museum has been reluctant to credit its public with much curiosity on that score. When it comes to more specialised or speculative bicycle design as well as the future of cycling infrastructure, the exhibition proceeds as if it were a matter only of style plus certain crude choices. A bike made of wood? A cycle lane in the sky? An electric motor for your Moulton? None of it seems relevant either to the reality of everyday cycling or to the functional allure of a beautifully made bike.

Cycle Revolution is a laudable overview of some aspects of cycle design and culture, but by the end I began to feel as if I were in a giant bike shop with inadequate pricing information and no chance of a test ride. There is no exhibition catalogue, thus little curatorial sense that bicycle design might have much to do with other types of design. By far the most engaging section of the show involves video profiles of designers and makers of hand-built bicycles, whose drawing, welding and skill with lugged steel frames and their subtly varied geometries comes closest to the intimacy of the daily rider with his or her machine.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.