Christopher Logue dwelled in a state of perpetual agitation that ranged from unbridled curiosity and enthusiasm to unbridled indignation and exasperation. If one were to find him at rest between the two poles, one wouldn’t have to wait long for the weather to shift dramatically. He was like that when I first met him in Melbourne, sometime in the 1980s, when he was sixty or so, and remained so over the course of our friendship. He was brilliant, thrilling company, and the most generous of friends, but unpredictable to say the least, which was, I suppose, part of the thrill. I shudder to think what he was like at thirty, in 1956, when he came back to London after five years in Paris. He could hardly have arrived at a more propitious moment, given his temperament and interests: poetry, theatre and politics, especially the collusion between capital and militarism. ‘London had changed,’ Logue later wrote in his memoir, Prince Charming. ‘There was a feeling of confidence in the air. What happened to Britain in the renowned 1960s – for me the period between 1956 and 1970 – came from this act of national will: the creation of the welfare state.’

Wand and Quadrant, Logue’s first collection of poetry, had been published a couple of years earlier. His considerable work in theatre and film as actor, playwright and screenwriter nourished the poetry, much of which was dramatic in nature, and also helped make him one of his generation’s finest readers of verse. Rather pleased with his performance as Cardinal Richelieu in Ken Russell’s 1971 film The Devils, Logue boasted to the director Lindsay Anderson that he had a future as ‘the only English poet/film star’. To which Anderson responded, sighing: ‘You will never be a star. You might become a featured player specialising in intellectual villains, artistic misfits etc.’

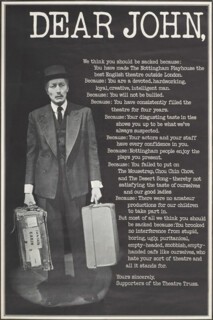

Logue was introduced to Anderson by Kenneth Tynan soon after his return to London. Around this time he had begun working on his translations from the Iliad with Donald Carne-Ross, and published a poem in the New Statesman grandly titled ‘To My Fellow Artists’. He found the atmosphere in London exhilarating, admiring the work, like Look Back in Anger, being staged at the Royal Court, and the Free Cinema movement (‘free’ from box office pressure or the requirements of propaganda) led by Anderson and Karel Reisz. Although he was becoming established as a young poet and his work was being published in the TLS and the New Statesman and broadcast by the Third Programme, Logue mostly wanted to be ‘part of the wave that had broken at the Royal Court’.

Anderson suggested that Logue read ‘To My Fellow Artists’ at the second Free Cinema Festival at the National Film Theatre. He hadn’t recited to an audience since a disastrous schoolboy episode twenty years earlier which resulted in his elocution teacher, Miss Crowe, telling his mother: ‘I am sorry, Mrs Logue, as your son is determined to indulge himself at the expense of my studio he and I must go our separate ways.’ Logue’s reading at the NFT, in front of several hundred people, was a great success. After the performance he met Reisz at the bar. ‘I think I’ll put “To My Fellow Artists” on a poster,’ he told Reisz, ‘and sell copies, stick them up.’

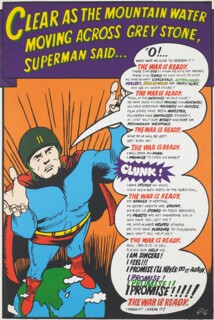

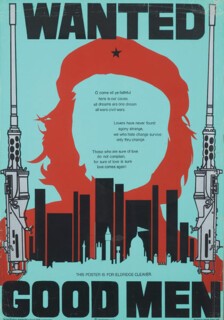

It’s unclear what made Logue think of producing poster poems. It was 1958. Ian Hamilton Finlay later scoffed at the notion that Logue invented the format, but Finlay, a congenital scoffer, didn’t produce ‘Le Circus’ until 1964, six years after Logue. A college dropout, a condition he seemed to relish, with the reverse snobbery common to many autodidacts, Logue had an encyclopedic knowledge of both high culture and kitsch. He would have been aware of the history of street literature from the 17th century on, handbills, street notices and especially broadside ballads, a fascination he shared with Brecht. The ballad form is fundamental to both their work.

Like Brecht, Logue did much of his finest work in collaboration. ‘I find it natural to collaborate with others,’ he remarked in a 1993 Paris Review interview, ‘on such things as posters, songs, films, shows. This is unusual in literary London. I like a worky atmosphere.’ And like Brecht, he had a genius for finding the best collaborators. To make the poster of ‘To My Fellow Artists’ he hooked up with the brilliant Germano Facetti, who became the head of design at Penguin Books in 1962. Logue spotted Facetti after Facetti designed the ceiling of the Poetry Bookshop in Soho. For someone so stubborn and so mercurial, Logue was surprisingly willing to bend to the wishes of his collaborators and enjoyed the process. Most poets don’t (including me).

When Logue decided to record his poetry to jazz accompaniment, an exercise popular in the later 1950s and the 1960s, and in almost every instance a near or total disaster, he somehow made a success of it. Red Bird, commissioned by the BBC in 1959, features him reading his poems with the backing of the Tony Kinsey Quintet. It wasn’t a cakewalk. ‘I’m amazed,’ Kinsey was heard to remark to a band member, ‘he’s supposed to be fairly intelligent.’ George Martin wound up producing Red Bird for EMI. That was Logue: he knew everyone, including (through Martin) the Beatles: ‘The hardest boys I’ve ever met,’ Christopher told me, ‘real thugs.’

It is next to impossible to write a successful ‘popular’ poem. In almost every instance, the product is transparently manipulative and cheap. Similarly, it’s next to impossible to write convincing political poetry. Political polemics generally work better when the cruder instruments of prose or popular song are employed. Logue’s taste for politically engaged writing seems to have been a result of his time in Paris. ‘We all agreed: literature had moral, as well as aesthetic power. It could do harm as well as good. Poets, novelists, dramatists and critics were responsible people, unable to avoid certain issues,’ Logue writes of this period in Prince Charming. ‘Similar convictions were to surface in London four years later,’ he went on, ‘but in that case it involved the rejection of a victorious past whose preoccupations no longer sustained the moral demands of the present.’ In London, he said, ‘confrontation, rejection and satire’ were necessary. When you look at the posters by Logue and his collaborators being shown at the Rob Tufnell Gallery in Pimlico (until 7 November), it’s difficult not to conclude that Swinging London was the perfect arena for Logue, with his bolshie temperament and very particular array of gifts.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.