Just as there are writers’ writers, so there are painters’ painters: necessary exemplars, moral guides, embodiers of the art. Often they are quiet artists, who lack a shouty biography, who go about their work with modest pertinacity, believing the art greater than the artist. Noisier painters sometimes unwisely patronise them. In France, the 18th century gave us Chardin, the 19th Corot, and the 20th Braque: all true north on the artistic compass. Their relationship with their descendants is sometimes one of influence, more usually one of semi-private conversation across the centuries (Lucian Freud doing versions of Chardin, Hodgkin painting ‘After Corot’). But it also goes beyond that – beyond admiration, beyond style, homage, imitation. Van Gogh, even as he was violently wrenching himself towards a form of painting which still startles us today, was filling his letters and his mind with thoughts of Corot (he also greatly valued Chardin). It was a tribute by the living artist to his predecessor’s clarity of seeing, an acknowledgment that this is what painting is. Just as the young John Richardson, visiting Braque’s studio for the first time, felt that he had arrived ‘at the very heart of painting’.

But these apparently quiet artists often turn out to have been more far-sighted and more radical than we assume. Corot, for example, once dreamed the whole of Impressionism. As Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo in May 1888,

When good père Corot said a few days before he died: last night I saw in my dreams landscapes with entirely pink skies, well, didn’t they come, those pink skies, and yellow and green into the bargain, in Impressionist landscapes? All this is to say that there are things one senses in the future and that really come about.

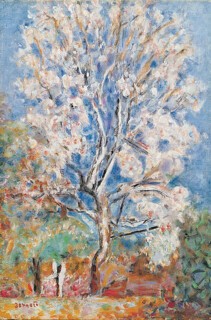

By the time of Van Gogh’s letter, the century-long struggle in French art between colour and line had been settled in favour of colour. (Settled for the time being, that is – until a few years later Cubism restored the primacy of line.) Corot pink developed into a leading, raging, shocking colour: the pink loitering surreptitiously in shadows, the overt pink of Monet’s haystacks and Van Gogh’s Pink Peach Tree, and still active in the pink of Bonnard’s last painting, Almond Tree in Blossom. But yellow and green were there too, as Van Gogh noted, and orange and red; oh, and blue and black. The tops were taken off all the tubes, and colour seemed to get its freedom and intensity back: richnesses that had been suppressed – either by self-censorship or academic dictate – since the days of Delacroix.

No one did colour more blatantly and more unexpectedly than Van Gogh. Its blatancy gives his pictures their roaring charm. Colour, he seems to be saying: you haven’t seen colour before, look at this deep blue, this yellow, this black; watch me put them screechingly side by side. Colour for Van Gogh was a kind of noise. At the same time, it couldn’t have seemed more unexpected, coming from the dark, serious, socially concerned young Dutchman who for so many years of his early career had drawn and painted dark, serious, socially concerned images of peasants and proletarians, of weavers and potato-pickers, of sowers and hoers. This emergence, this explosion from darkness, has no parallel except for that of Odilon Redon (who was prompted into colour more by internal forces, whereas Van Gogh was prompted into it externally – first in Paris by the Impressionists, and then by the light of the South). Yet there are always continuities in even the most style-changing of artists. Van Gogh’s subject matter, after all, remained much the same: the soil, and those who tend it; the poor, and their stubborn heroism. His aesthetic credo did not change either: he wanted an art for everyone, which might be complicated in means but simple to appreciate, an art that uplifted and consoled. And so even his conversion to colour had a logic to it. In his youth, reacting against the stolid piety and conformity of the Dutch Reformed Church, he had lurched not into atheism but its opposite, evangelism. His notion of working as a priest among the downtrodden was to end no more successfully than most of his other youthful schemes; but the fundamentalist, all-or-nothing streak in human beings, once aroused, never entirely goes away. So the striving painter who, in the most successful of his schemes, took himself off to Arles, first working alone, then alongside Gauguin, then alone again, then in the mental hospital in Saint-Rémy, was continuous with that violently principled younger man: he had grown up to become an evangelist for colour.

It has become harder over the last 130 years or so to see Van Gogh plain. It is practically harder in that our approach to his paintings in museums is often blocked by an urgent, excitable crescent of worldwide fans, iPhones aloft for the necessary selfie with Sunflowers. They are to be welcomed: the international reach of art should be a matter not of snobbish disapproval but rather of crowd management and pious wonder – as I found when a birthday present of a Van Gogh mug hit the mark with my 13-year-old goddaughter in Mumbai. But there is so much noise around Van Gogh besides the noise of his paintings. There is the work, then the several hundred thousand words he himself wrote, then the biographies, then the novel, then the film of the novel, then the gift shop, then even (as at the National Gallery) the Sunflower bags in which you cart your treasures away from the gift shop. The painter has become a world brand. And so there is an inevitable coarsening, at the micro as well as the macro level: Irving Stone’s 1934 novel, made into an honourably hilarious film in 1956 with Kirk Douglas as Van Gogh and Anthony Quinn as Gauguin, was called Lust for Life. The original Dutch phrase, as rendered in the great six-volume set of letters published in 2009 by the Van Gogh Museum, was ‘zest for life’.

We have a problem of seeing, just as we often have a problem hearing (or hearing clearly), say, a Beethoven symphony. It’s hard to get back to our first enraptured seeings and hearings, when Van Gogh and Beethoven struck our eyes and ears as nothing had before; and yet equally hard to break through to new seeings, new hearings. So we tend, a little lazily, to acknowledge greatness by default, and move elsewhere, away from the crowds discovering him as we first discovered him. But if, seeking silence and untrammelled Van Gogh, we then retreat into the art book, we are let down differently: however faithful the colour reproduction, the flat page always suppresses the urgent impasto of the paint surface, an impasto so thickly wet that the painter was sometimes kept waiting weeks before he could safely post off his latest canvas to his dealer-brother Theo. Julian Bell, in his useful short biography and appraisal, aptly describes Starry Night over the Rhône as ‘closer to a sculptural relief than a reproducible flat image’.

The life gets in the way as well. We have become over-familiar with the lineaments of the biography. The poverty, the rage, the despair, the prostitutes, the madness, the ear-cutting, the suicide; the lifetime of apparent failure followed by a deathtime of astonishing success. Back-projecting, we read the painter’s encroaching madness into the paint: those whirls and whorls and disturbed trenches of paint, those black skies, those blacker crows taking off across the wheatfield. He suffered so that we might enjoy. Inevitably, we are tempted to equate the madness with the genius, to propose Van Gogh as the ultimate modern exemplar of the myth of Philoctetes: of the wound and the bow. And if that now feels a little dated, a little obviously reductive, the furious belief in the locatability of artistic creativeness remains, and has lately moved into genetics. A recent study of 86,000 Icelanders purported to find that those with genetic risk factors for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder appear to have a greater chance of being creative. But sometimes the archer pulls the bow despite the wound rather than because of it. This is certainly what the painter himself thought. Less than three months before his death, Vincent wrote to Theo: ‘Ah, if I’d been able to work without this bloody illness! How many things I could have done …’ One of Van Gogh’s uncles went to pieces and killed himself, while his sister Willemina was committed to an asylum in 1902 and spent 39 years there in near-total silence. Neither of them painted much. This seems to me to prove that it was madness which ran in the family rather than creativity.

Van Gogh’s life story often moves us to terror and pity. We ache for him when Theo, though very good at business, up to speed with Impressionism, and able to sell both Monet and Gauguin, cannot find a buyer for more than a single picture of Vincent’s. But this sad fact also spurs us towards self-congratulation: look how we who have come later appreciate your work, how superior our eye and taste and sympathy are to those who snubbed and misprised you back in the day; look too at how much money our tycoons and art institutions are willing to pay for your treasured work. The most valuable painter of Van Gogh’s day was Meissonier, that Alexandre Dumas of 19th-century painting, whose fame, subject matter (typically, Napoleon’s triumphs and disasters) and traditional technique we might plausibly expect to have repelled the younger painter. Van Gogh disdained what he called ‘studio chic’, even if painting out of doors meant getting flies, dust and sand stuck to your canvas. Meissonier became the world’s most expensive painter in his own lifetime; Van Gogh did not achieve that rank until a century into his deathtime.

Apart from finding a time of day when the art gallery is reasonably empty, one way of trying to get the untrammelled Van Gogh back into our heads is to follow the painter’s own account of his life and art. Bell calls those six volumes of letters ‘the greatest commentary any artist has ever supplied on his own work’. This new rescension, despite its single volume, contains a very substantial number of words: by my count, maybe 400,000 of the original 850,000. But the size, and the density, matter. The movement of Van Gogh’s brain, and eye, and hand are here recorded at great – often angry, sometimes self-pitying, sometimes paranoid – length. Bell, having read all six volumes, admits that while he loves the work and greatly admires the letters, ‘I do not always like him.’ Certainly, Van Gogh was the flat-sharer from hell, an insistent, overbearing presence, needy, demanding, free with advice and always knowing better. When his sister-in-law gives birth, Uncle Vincent reveals himself as a sudden expert on childcare, even unto breastfeeding. But readers of the letters aren’t being asked to share his flat, only his extraordinary mental and artistic struggle. Bell’s caveat reminded me of being in Toronto once on litbiz and running into an exhausted Michael Holroyd, then world-touring the third volume of his Bernard Shaw biography. He explained his travails with a resigned good humour: ‘They keep asking me if I still like Shaw. It’s … it’s … irrelevant.’

Even so, Van Gogh’s is an intense presence to be with; often a hectoring one, even when hectoring only himself. He is frequently dismayed by how poorly he gets on with others, how easily he offends or irritates them – not that he then moderates his behaviour. Obliged to return home to Nuenen for a month or so, he imagines his parents viewing his visit as like having ‘a large, shaggy dog in the house … with wet paws … And he barks so loudly.’ This intensity is off-putting to women: ‘No, nay, never’ is the celebrated triple refusal he gets when he proposes to Kee Vos; characteristically, he believes that, given time and access (both of which were sternly refused by the woman in question), he could turn this around into a ‘Yes, yea, now.’ He addresses the world with similar pressing proposals, also designed to solve everything in his own life: he must go to America, must go to the tropics, he and Theo must go over to England and sell the Impressionists there (a daft idea at the time, and still daft when it came to the Post-Impressionists). His notion that the Impressionists should form a kind of commercial guild sounds more practical, except that by the time he reached Paris they were already on their eighth group exhibition; as Bell puts it, ‘Vincent was … catching up with the movement at the moment it evaporated.’ Less workable still was his notion that artists should live with their dealers, who would look after ‘the housekeeping side’ of things, which included the cooking (Van Gogh was a terrible cook, though Gauguin an excellent one). He was also forever convinced that the art market was dangerously overheated, in a state comparable to that previous bubble, ‘tulip mania’. (What would he have made of the contemporary market – and his own presence in it?) At the personal level, he largely accepted the deal that giving yourself to Art meant giving less of yourself to Life, and Balzacianly believed in the connection between the creative and the sexual juices: ‘If you don’t fuck too hard, your painting will be all the spunkier for it.’ When furnishing the Yellow House in Arles, he bought 12 chairs. Yet he never entertained, and didn’t have any disciples.

But these moanings and rantings and madcap schemes are background noises to a process of artistic heroism, of determination in the face of discouragement – determination, indeed, in the face of his own character. Art is a matter of daily, hourly grind. At the same time, that grind is complicated and layered, a mixture of hard practicality and intense dreaminess. Van Gogh took pointillism (which, being semi-scientific, is essentially a calm medium) and made it something ferocious; he turned himself into the hinge between Impressionism and Expressionism. He was also virtually self-taught – except that he learned from the best teachers, those who had preceded him. And it is salutary to be reminded that painters’ sympathies are often more various than we might naively – or in a spirit of aesthetic political correctness – expect them to be. So, although we can make sense of Van Gogh’s admiration for père Corot and père Chardin, it comes as a proper surprise that on many occasions he goes against the obvious grain in his admiration for – yes – Meissonier: ‘Now a Meissonier, if you look at it for a year there’s still enough in it to look at the next year, never fear.’ Even when he has absorbed the full whack of Impressionism, he believes in artistic continuity, in that essential ongoing conversation with the past. He rejects any idea of a ‘rigorous separation’ between the bold new movement and what went before: ‘I find it a very happy thing that in this century there have been painters like Millet, Delacroix, Meissonier, who cannot be surpassed.’

Public events impinged little on his consciousness: in these pages there is one reference to the death of Kaiser Wilhelm – his main concern being the effect it might have on the art market – and one to the right-wing political chancer General Boulanger. He is interested only in those things he is interested in, but they become a full commingling: ‘Books and reality and art are the same kind of thing for me.’ And so, like Cézanne, he read and read: George Eliot, Dickens (‘noble and healthy’), Charlotte Brontë, Shakespeare, Aeschylus, Balzac, Flaubert, Maupassant, Daudet, Zola (‘healthy stuff and clears the mind’), Longfellow, Whitman, Harriet Beecher Stowe. He approves of Goncourt because he is ‘so conscientious, and so much toil goes into it’. He is himself an excellent writer: intense, observant, colourful, close to life. He can be wittily dismissive: Louis XIV is ‘that Methodist Solomon’. He can describe going down a mine with the clarity (and social passion) of Zola. Or take this description of the clothes of peasants in and around Nuenen:

The people here instinctively wear the most beautiful blue that I’ve ever seen. It’s coarse linen that they weave themselves, warp black, weft blue, which creates a black and blue striped pattern. When it’s faded and slightly discoloured by wind and weather, it’s an infinitely calm, subtle shade that specifically brings out the flesh colours. In short, blue enough to react with all the colours in which there are hidden orange elements, and faded enough not to clash.

It’s safe to say that peasant linen has rarely been looked at with such a meticulous and sympathetic eye.

Reading these letters from Van Gogh’s lifetime, we cannot unknow what is to happen in his deathtime. So the clang of posthumous irony is often unbearably loud. Who but specialists have nowadays heard of the French painters Georges Jeannin (1841-1925) and Ernest Quost (1844-1931)? Yet more than once Van Gogh makes this comparison: ‘You know that Jeannin has the peony, Quost has the hollyhock, but I have the sunflower, in a way.’ In a way! The same year, he sums up his life in a mood less of self-pity than sober realisation: ‘Now, myself as a painter, I’ll never signify anything important, I sense it absolutely.’ His early Calvinism might have been overpainted with Zola’s social determinism, but you could easily imagine yourself done for under either dogma. As for his suicide: though the subject recurs at intervals through the letters, the act itself is never applauded. He cites the remedy of ‘the incomparable Dickens’ against thoughts of suicide: ‘a glass of wine, a piece of bread and cheese and a pipe of tobacco’ (he has added the bread and cheese himself). He quotes Millet to the effect that ‘suicide is the act of a dishonest man.’ He maintains that the deed ‘truly makes murderers of one’s friends’. Also, that ‘a failed suicide is the best remedy for suicide in the future.’ Could he have been trying to miss when he aimed the revolver at his heart?

In the last weeks of his life, one colour used in his work is mentioned repeatedly: pink. He writes of ‘the olive trees with the pink sky’, ‘pink roses against a yellow-green background’, ‘a study of pink chestnut trees’, ‘the Arlésienne … in pink’, and ‘some sunny pink sand’. Is this chance? Coincidence? Or was that old, revolutionary pink of the dying Corot’s dream coming back to farewell him?

‘What pleases the PUBLIC is always what’s most banal,’ he wrote to his brother in 1883. But nowadays Van Gogh pleases the public enormously. So has he become banal? Could our difficulty in being able to see him properly be a sign that there is only so much looking to be had, and/or that with age we grow out of him? Oddly, no. He isn’t one of those painters – like, say, Degas or Monet – who, over the decades, refine and deepen our vision. I am not sure that Van Gogh’s paintings change for us very much over the years, that we see him differently, find more in him, at sixty or seventy than we did at twenty. Rather, it is the case that the painter’s desperate sincerity, his audacious, resplendent colour and his intense desire to make painting ‘a consolatory art for distressed hearts’ take us back to being twenty again. And that is no bad place to be. Perhaps it’s time for a selfie with Sunflowers.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.