My experience with death has been minimal and to varying degrees distant. I have never been in the presence of anyone when they died. The likely ones, family deaths, the deaths of my father and mother, are remote in space and time. My father died when I was 19, somewhere else, and I was told of it by phone. In the case of my mother I didn’t even know she had died in the 1980s until my daughter found out eight years later.* Between late 2010 and early 2011 there were two deaths; one a very elderly, long-time friend, Joan, and the other, sudden and tragic, a couple of months later, in 2011, my first husband, father of my daughter, and my oldest friend, Roger. Then, during the final quarter of 2013, there were two more deaths within a month of each other, neither of them really unexpected after years of frailty, but both, Doris Lessing and her son, Peter, having attachments of some complexity to each other, to my daughter and to me, going back even before I went at 15 to live in their house.

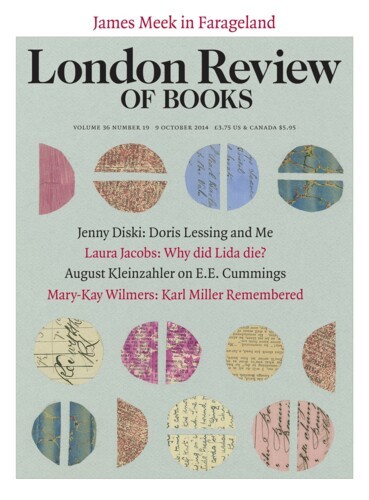

When she died last November at the age of 94, I’d known Doris for fifty years. In all that time, I’ve never managed to figure out a designation for her that properly and succinctly describes her role in my life, let alone my role in hers. We have the handy set of words to describe our nearest relations: mother, father, daughter, son, uncle, aunt, cousin, although that’s as far as it goes usually in contemporary Western society.

Doris wasn’t my mother. I didn’t meet her until she opened the door of her house after I had knocked on it to be allowed in to live with her. What should I call her to others? For several months I lived with Doris, worked in the office of a friend of hers and learned shorthand and typing. Then, after some effort, she persuaded my father to allow me to go back to school to do my O and A levels. As a punishment, he had vetoed further schooling after I was expelled – for climbing out of the first-floor bathroom window to go to a party in the town – from the progressive, co-ed boarding school that Camden Council had sent me to some years before. (‘We think you will be better living away from your mother for some of the time. Normally, we would send you to one of our schools for maladjusted children, but because your IQ is so high, we’re going to send you to a private school, St Christopher’s, which takes a few local authority cases like yours,’ the psychologists at University College Hospital had said to me, rather unpsychologically. I was 11.) My father relented and Doris sent me to a progressive day school.

At the new school, aged 16, as I tried to ease myself back into being a schoolgirl after my adventures in real life (working full time in a shoe shop, a grocery shop and then being a patient in a psychiatric hospital), I discovered I had to have some way of referring to the person I lived with to my classmates. It turned out that teenagers constantly refer to and complain about their parents and they use the regular handles. Not that I would, under the circumstances, have complained. But could I refer to Doris as my adoptive mother? She hadn’t adopted me, although she’d suggested it. We even went to see a solicitor in the first month, who must have had a wilful teenager of his own, because instead of coolly discussing the legal situation, he turned to me and ranted about the awfulness of teenagers these days, my undeserved good fortune, the selfishness of giving my parents so much worry, and his inability to believe I had any psychological problems – I merely wanted special treatment and attention. I stared at him, feeling both slapped and in the middle of someone else’s cartoon, but before he could finish what sounded uncannily like the solicitor’s speech in John Osborne’s play Inadmissible Evidence, a year or so later, Doris grabbed my sleeve and we escaped down the winding wooden staircase, with the sound of his voice echoing behind us. In addition, my mother had one of her screaming fits and threatened to sue Doris for alienation of affection (hilarity ensued) if she tried to adopt me. So that was quietly dropped. I sometimes said ‘adoptive mother’ anyway, as an easy though inexact solution. It wasn’t only for form’s sake that it mattered how I referred to her; whenever I was called on to say ‘Doris, my er … sort of, adoptive mother … my er … Doris …’ to refer to my adult-in-charge, I was aware of giving the wrong impression.

For some reason, being precise, finding a simple possessive phrase that covered my situation, was very important. I didn’t want to lie and I did want to find some way of summing up my circumstances accurately to others. But I hadn’t been an adopted child. Both my parents were still alive and (regrettably, in my view) in contact with me. The changeover in my caretakers (‘my caretaker’?) didn’t happen until I was at an age when some had left school and gone to work, as I had after my expulsion from St Christopher’s, until I ran away from my father in Banbury and went to stay with my mother in Hove, in her very small, one-bed bedsitting-room. That had lasted only a few days before the wisest move seemed to be to take what remained of my mother’s Nembutal, lie down neatly on the bed and wait to die. ‘How can you do this to me? Why can’t you be decent, like other children?’ she screamed when she found me. The night before in the bed we shared she had reached around my back, which was turned to her, and begun to caress my vulva. When I protested, she said: ‘What’s the matter? There’s nothing wrong. I’m your mother. You’re still my little girl.’

It was deemed a good idea to keep me away from my parents, so after they’d stomach-pumped me, they popped me into the Lady Chichester Hospital in Hove. It was a small psychiatric unit in a large detached house, consisting mostly of young people, though none as young as I was. I became the official baby of the bin, and both staff and patients looked after me and tried to shield me from the worst of the outbreaks of other people’s madness. I, of course, was fascinated and felt quite at home and well cared for at last. The weekly 15 minutes with the therapist was always the same.

‘Is there anything you want to talk about?’

‘Uh, no.’

After a few weeks of this I became convinced that the shrink knew something I didn’t. He couldn’t simply have meant what he said. The only thing I could think of was that I was pregnant, which, although I had only had sex with one person, several months before, I decided must be the case. I developed a secret terror that I was miraculously with child and the doctor was waiting for me to come to terms with it, though I never spoke of it to him. Apart from that, I wasn’t mad at all and they weren’t trying to treat me. I stayed there for four months, without medication, spending long periods sitting on the beach in Hove, staring at the sea – it was a winter of unprecedented ice and snow – while they tried to figure out what to do with me. After, for some reason, hankering for a job as a lab assistant, for which, of course, I was unqualified, I was eventually taken on by the Oxford Street department store Bourne and Hollingsworth as a sales assistant, an offer I was advised by Dr Watt, the psychiatrist in charge, to accept, because B&H had a hostel in London for its employees. But before that plan could be put into action, I received a letter from Doris, saying that although I didn’t know her, she knew about me from her son, who had been in my class at St Christopher’s. Much over-excited gossip, you can imagine, had been going on there about the wicked Jennifer Simmonds who’d got expelled and was now in a madhouse. The previous holder of the title of wickedest girl in the school had been Fanny Hill (sic), daughter of the historian, and mischievous child-namer, Christopher Hill.

Over the years I called Doris ‘the woman I live with’, which I worried could be taken to have something a little unseemly or suggestive about it in those not quite yet permissive days; ‘the woman whose house I live in’ (less unseemly but odd); or most often, ‘Doris, my mumble, mumble, mumble’, ‘the person who bla bla bla’. Or I took a deep breath and went the whole hog: ‘Doris, who invited me to go and stay at her house when she heard …’ But with that the conversation was scuppered and once again, I’d end up telling the whole convoluted tale, which fairly rapidly, since Doris had also sent me to the Tavistock Adolescent Clinic to get ‘sorted out’, had become very boring, like a straightforward writing down of my life story. For a while, I decided on ‘foster mother’ but the ‘mother’ part of it made me cringe (as it certainly made Doris cringe), and a friend, who wasn’t English and didn’t know about the system of care for children, objected that it made her sound as if she had taken me in for money. So taking account of cultural understandings, another possible designation hit the dust. I occasionally tried a light-hearted ‘my benefactor’, which had a theatrical and comic edge to it, but once again required a story to be told. There was ‘my friend, Doris’ but that didn’t convey the dynamics of the relationship or the age discrepancy. ‘My fairy godmother’ was kept for those occasions when I was needing to end a conversation for my lack of interest in it. ‘Auntie Doris’ always got a laugh from Doris, and I think she suggested it as a joke when the matter came up. The name thing was an ongoing problem.

Sometimes, for lack of a solution, I thought I’d simply call her ‘my mother’, but that made me so inordinately uncomfortable, ‘mother’ and ‘my’ being more than doubly cringeworthy, that even now I feel the need to reiterate that she wasn’t really my mother. We never spoke about it in more detail than the Auntie Doris joke, but she must have had a sense of it because when my daughter was about a month old and lying on the carpet in her flat, Doris said, out of the blue, in the awkward, clipped and embarrassed tone she used for any discussion of our relationship, which I very well recognised by then: ‘Do you want her to call me grandma? Or some sort of thing like that?’ I took it for the kindly and difficult gesture it was, but awkward and embarrassed myself by her manner, I said I thought ‘Doris’ would be the best name to call her. In any case, I said, ‘she’s got two grandmothers, even if one is invisible – please god.’ I was quite taken by surprise at the thought that all along while I was trying to figure out how to refer to Doris, I actually had a real mother to call my own. But having thought that, it seemed irrelevant.

As with my cancer diagnosis, it’s hard to avoid thundering clichés when writing about the start of my relationship with Doris, and hard not to make it sound either Dickensian or uncannily close to the fairy tales we have in the back of our minds. ‘It’s like something out of a fairy story’ was a phrase people often said to me when they learned how I got to live with Doris. To which I would answer yes, or sort of, or say nothing at all. Or if I had the will, I would say something to the effect that the Cinderella fairy story of Doris and me was a rare instance of life after the ellipsis at the end of most fairy stories. And they lived happily ever after. People usually didn’t much like that answer, because it messed up the simplicity of the story, and reminded them that Doris was not a handsome prince, or I the foundling whose innate nobility was recognised by a prince of the true blood.

Still, it was close enough to the old tales. I was a sort of foundling. I was sort of recognised as or was elevated to being worthy of attention. I did proceed into another life. Or at least into a life that was probably different from the one I might have had if Doris had not issued her invitation and I’d remained on the Bourne and Hollingsworth path. Doris would have said firmly ‘completely different’. Her view of the upshot of the B&H move was clear; she didn’t think the chances of my survival very high. She even referred to me in interviews (in spite of our ‘I won’t talk about you if you don’t talk about me’ pact) as a waif whom she had rescued, and she frequently told me and others that, had I gone to the London hostel and a job as a salesgirl, I would not have become a writer, or even a managing director of B&H, but would have ended up pregnant and stuck with a child in an awful marriage (in that order), or pregnant and dead (in that order), or pregnant and a drug addict and dead (in any order – they were synonymous). She was adamant that I would have been dead before I was out of my teens. Being pregnant, married and/or a junkie represented no life to Doris. In fact, in relation to me and other young women, she considered that ‘pregnant’ and ‘married’ were alternative terms for ‘death’. Only years later, when a challenging psychoanalyst queried the standard story, which I had thoroughly introjected, did I come to think that I would have had some life, a life, had Doris not intervened, which would still have been my own.

In his letter to Doris from St Christopher’s after I was expelled (there were four of us, felled with one blow) and ‘locked up’ in the madhouse, her son Peter wondered, in all innocent generosity since we had by no means got on with each other at school, if, since I was ‘quite intelligent’, they might not be able to help me somehow. A few years later, Doris gave me Peter’s letter. In fact, the Lady Chichester Hospital was no hellhole, and was for people who were more neurotic than mad. They were simply parking me while trying to find something to do with me that would keep me away from both of my unsatisfactory parents. Doris said in her letter to me that she had just moved into her first house, that it had central heating (she was particularly proud of that) and a spare room, so I might like to stay there, and perhaps, in spite of my father’s reluctance, go back to school to get my exams and go to university. It wasn’t clear in the letter how long I was invited to stay for, but the notion of going to university suggested something long-term, because I’d never heard of anyone going to university without having somewhere to live during the vacations.

I read the letter many times. The first time with a kind of shrug: ‘Ah, I see. That’s what’s going to happen to me next.’ Unexpected things had happened to me so frequently and increasingly during my childhood that they seemed normal. I came to expect them with a Micawber-like passivity. Then I read the letter again with astonishment that I did, after all, have a fairy godmother. Then fear. Then a certain amount of disappointment, and some real thought about whether to accept or not, because I was excited about starting a new grown-up life in London as a salesgirl in Oxford Street, in a hostel: girl things, make-up, camaraderie, misbehaviour, advice. Like boarding school or the friendly psychiatric community I was already quite contentedly in, but with pay and without pills. And finally all these responses melded together like all the colours of plasticine making grey sludge, and I had no idea how to respond either to my own fears and expectations, or to this stranger for her invitation. So Doris was not my mother. And aside from awkward social moments, what she was to me was laid aside along with other questions best left unthought.

The child was left with me in this way. I was in the kitchen and, hearing a sound, went into the living room, and saw a man and a half-grown girl standing there. I did not know either of them, and advanced with the intention of clearing up a mistake. The thought in my mind was that I must have left my front door open. They turned to face me. I remember how I was even then, and at once, struck by the bright hard nervous smile on the girl’s face. The man – middle-aged, ordinarily dressed, quite unremarkable in every way – said: ‘This is the child.’ He was already on the way out. He had laid his hand on her shoulder, had smiled and nodded to her, was turning away.

I said: ‘But surely …’

‘No, there’s no mistake. She’s your responsibility.’

He was at the door.

‘But wait a minute …’

‘She is Emily Cartright. Look after her.’ And he had gone.

‘Emily’s you, of course,’ Doris told me, handing me the final draft manuscript of The Memoirs of a Survivor in 1973. She always let me know when I appeared in her books, or when she used something I’d told her about, events from my past or present. She also told me who the other characters were. Not all of them had familiar real-world models, but many of the key characters in her stories and novels did, even some of the science fiction and fantasy ones. By the time she published The Memoirs of a Survivor the following year, I had been back in the bin, two different ones in London, the north wing of St Pancras Hospital for several months and, not long after that, the Maudsley for nine months. Another book, Briefing for a Descent into Hell, published in 1971, centred on the story of my relationship with one of the other patients in St Pancras, while the later book, Memoirs, concerned, in part, not just a dramatisation of my arrival at Doris’s, but also a fairly accurate and equally dramatic account of the time in my life, in the early 1970s, when Roger and I ran an ‘alternative’ school for some local kids, who had been persistently truanting and running wild and were now threatened with being taken into care. Some of the later books had minor characters and odd events that were me and mine, but Memoirs and Briefing sit on my shelves quietly filled with Doris’s take on me, and aspects of my life, reinterpreted for fiction. I only read each of them once, in manuscript. Until now, they’ve been patiently bearing my sideways glance, waiting for me to take another look, and to think about what I think about them, in terms of my real life and also in terms of fiction, and all the ways in which writers, including me, quite legitimately appropriate bits and pieces of lives and people for their own ends. The writer in me never had much trouble with the books that Doris solemnly indicated had characters who were ‘you’, and I felt only mildly aggrieved at her use of some of my best stories. After all, however convinced I was that I was a writer, I hadn’t ever finished anything I started of my own writing. The sound of the voice in my ear as I typed, repeating ‘this is crap, this is crap,’ ensured that everything ended up in the wastepaper basket. So I had no real claim on my stories. And then, once I began writing myself, I realised it didn’t matter what Doris might have done with those stories (her stories, once she wrote them), they were still available to me to do with as I wanted.

Before her invitation letter to me, Doris had an exchange of letters with Dr Watt in which he was extremely cautious, appearing to be worried about litigation from my parents, and perhaps from Doris, if he said anything too definite about them, or me, or too positive about Doris’s plan, but essentially giving her the go-ahead. She was also visited by my father, the woman he lived with, Pam, and, my bête noire, Janet, Pam’s daughter, a few years older than me and a prissy girl who told on me when she found me smoking in my room. My father, apparently and not surprisingly, tried to flirt with Doris and when that didn’t seem to be working, to impress her with his knowledge of literature, which was less than very slight. Doris, in a follow-up letter to me, told me about it; she said that my father was preposterous, but she could handle him. Pam sat as she always did with her lips tightly pressed together and pursing them in and out with disapproval every time my name was spoken, and Janet piped up that I was so awful, and as an example, I had even wanted to go on the Aldermaston March with all those dirty beatniks. Not a good move, since Doris was a regular on the march herself.

Then it was all settled, although my father was adamant that I had to be punished for being expelled by not being allowed to go back to school. I’d had the two letters from Doris, and I replied thanking her for giving me such a wonderful opportunity (I did say that it was like a fairy story) and promising not to be any trouble, but warning her to ignore my father’s accusations. He would, I was sure, tell her that I was wicked and worst of all a smoker, which I was but I’d stop if she wanted me to. It was this letter, Doris told me later, as did some friends of hers she spoke to at the time, that convinced her she was doing the right thing. It was intelligent (that again), humorous and well written. She was sure after reading it that having me in the house would work out, though I don’t think it was clear in her mind any more than mine how long that was to be for.

So sometime in late February 1963, my mother and I took the train from Brighton to Victoria and then the Underground to Mornington Crescent (yes, really) and the ten-minute walk from the station to the street where Doris had bought her first house. It was opposite a concrete and glass boys’ secondary modern school, and the houses on the other side were in the very early stages of gentrification. Most of them were quite dingy from the outside, council-owned houses rented to low-income families. Doris was one of the first to buy quite cheaply into the potential of the Georgian three-storeyed terraced houses, with their long, elegant windows and steps up to the front door. Black, I think. I knocked on the door, wearing an awful mustard yellow woollen coat with a velvet collar and kind of pleated below a dropped waistline, which my mother thought was very grown-up and respectable, and which I would never wear again.

Doris answered the door with a small kitten in her arms.

‘Look,’ she said. ‘She can be your cat. Some friends of mine got her, but they have no idea how to look after a cat. They were feeding her on lobster soup. She’s called Grey Cat. Come in.’ She was polite and I thought rather shy. She was in fact nervous at this first encounter with my mother, who Dr Watt had warned her was ‘a very difficult lady’. It was lunchtime, and she had made soup for us, rather than for Grey Cat. It was a recipe she made often, with Campbell’s chicken soup and an added tin of sweetcorn. My mother and I sat on the bench Doris had had built along one side of her kitchen table, while she sat on the other side on a chair, with access to the stove. I thought she hadn’t finished doing up the house, and I was rather downhearted at the untidy state of the kitchen, the surfaces covered with glass jars and tins waiting for shelving that never got round to being built, the uncurtained window, and especially the bare floorboards which, being a lower-middle-class child of East End Jews, I thought were waiting for lino or tiles to be laid over them, rather than being fashionable bare boards waiting only for a final sanding. It didn’t seem at all the sort of respectable place my mother would approve of, and I heard my mother in me deploring it and the owner who allowed it to be seen by visitors in its slovenly state. But very soon, along with my discarded coat, the chaotic kitchen seemed to be a proof of my entry into another kind of living altogether and one that I thought I might get the hang of if I paid attention.

I liked the soup, but have no recollection of the conversation. Doris said that my mother had done all the talking. She complained about my father’s treatment of her, my treatment of her and the awful life she had come from in her miserable childhood and was now plunged back into. The shame of living on the dole in one room and the added shame of having an ungrateful daughter who behaved so badly she was put in a mental hospital, and now was going to be taken in by a stranger, who, she warned Doris, shouldn’t herself be taken in by me. ‘I’m the one who should be given a new home and looked after,’ Doris told me my weeping mother had said. I don’t remember, but it sounded like her. I imagine I was suffering my usual excruciating embarrassment when my mother had a meltdown in public. Doris said later that she’d felt sorry for the poor woman who was so disappointed by life, but she could only take on one of us, and that one was me. After a couple of hours, Doris eased my mother, still complaining about me, still crying about my father and her dreadful life, out of the house, and then, since it was term time and Peter was away at St Christopher’s, Doris and I were left alone to figure out how we were to get on with each other.

You can read the next instalment of Jenny Diski's memoir here (and the first one here).

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.