On 16 October 1940 the house in Tavistock Square in which Virginia Woolf had lived for 15 years was destroyed by a bomb. The first image in the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition Virginia Woolf: Art, Life and Vision (until 26 October), which claims to provide ‘a visual narrative akin to a portrait’ by looking at ‘telling ingredients in each period of her life’, is a blown-up photograph of the exposed side wall of the house. Some of the panels that Woolf’s sister, Vanessa Bell, and Duncan Grant had painted for the third-floor drawing room are, as Virginia told them, ‘still pendant’. ‘I cd just see a piece of my studio wall standing: otherwise rubble where I wrote so many books. Open air where we sat so many nights, gave so many parties.’ She felt guiltily relieved that the house had been destroyed: they’d moved out the previous year, fed up with the noise caused by the building of a new hotel next door, but were still paying rent since the war had, obviously enough, made it hard to sublet. To ‘see London all blasted’, however, ‘raked my heart’. Her feelings for the city were, Woolf claimed, her ‘only patriotism’.

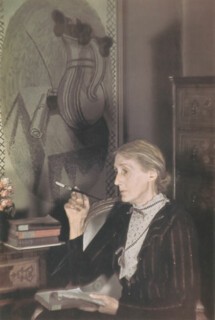

Leonard and Virginia Woolf had moved back to central London from Richmond early in 1924 after a concerted campaign from Virginia to convince her husband that her health was robust enough to cope with its excitements. Her pleasure in the city is evident throughout Mrs Dalloway, which was published in 1925, and her pleasure in her new house is shown by her decision to pay Bell and Grant £25 to decorate the drawing room. This must have been done straightaway because, in November 1924, the room was featured in Vogue, then edited by Dorothy Todd. ‘The walls are pale dove-gray,’ we’re told, ‘the panels glossy white with tomato-red borders and oval “fonds” alternately in sienna pink and maple yellow. The subjects are painted in umbers, browns and white, with touches of lettuce-green.’ The panels show vases, a classical-looking head of a woman, musical instruments, books, fruit and flowers. Tiles were made for the fireplace, and dots painted along the edge of the mantelpiece; Woolf later wrote to her sister asking ‘how to make lavender blue’ because the dots had been repainted a ‘dull sea green’. In 1939, shortly before they left Tavistock Square, she was photographed in the room by Gisèle Freund. These pictures, usually seen in black and white, are shown in colour at the NPG, but possibly because of the umbers and browns of the panels and the Victorian-looking blouse Woolf wears in one photograph, the colour prints themselves look quite antique.

Woolf described the prospect of being photographed by Freund as ‘detestable and upsetting’. The demand for pictures and interviews had been an unwelcome accompaniment to her increasing fame. And she minded more about the images than the words they accompanied. She’d never much liked being painted or photographed: she felt uncomfortable with the scrutiny and didn’t like feeling that her identity was being fixed, settled, by someone else. There are portraits of her, but fewer than one might expect for someone who was close to several artists. The NPG exhibition includes four by her sister done in 1912; the two most successful show her sitting crocheting in an armchair and sleeping in a deckchair. In both her face is obscured, but the poses are characteristic. In 1931 Woolf agreed to sit for Bell and the sculptor Stephen Tomlin, ‘pinning me there, from 2 to 4 on 6 afternoons, to be looked at; & I felt like a piece of whalebone bent. This amused & interested me, at the same time I foamed with rage.’ In the resulting sculpture she looks alarmed and alarming, with staring eyes. Her anxieties aren’t always so evident: she sat for Man Ray in 1934 and looks cool, quizzical and rather formidable. Again, snapped by Leonard in September 1932 with T.S. Eliot and his wife, Vivienne, whom he was about to leave, she stands calmly beside Tom. Vivienne, seemingly excluded by the successful pair, stands at a distance, hands clasped behind her back, feet together, dressed entirely in white. She was ‘wild as Ophelia’, Woolf wrote, but ‘alas no Hamlet would love her, with her powdered spots.’

There are endless snapshots of Woolf, but the NPG show has managed to find some unfamiliar ones, a series taken by Ottoline Morrell when Woolf came to stay at Garsington Manor in June 1926. It’s possible that her look of self-assurance in these photos is connected to her pleasure in her outfit. She’s wearing a patterned dress and silk coat by the couturier Nicole Groult, Paul Poiret’s younger sister, commissioned for her by Dorothy Todd’s girlfriend Madge Garland, then Vogue’s fashion editor, whom Woolf had seen wearing the outfit. Garland thought it made Woolf look ‘supremely elegant’, Frances Spalding writes in the exhibition catalogue.* There was also a hat, presumably not the one Woolf was wearing when she went to see the latest Stravinsky ballet with Vita Sackville-West just before she visited Garsington, ‘a sort of top-hat made of straw with two orange feathers like Mercury’s wings’, Sackville-West wrote to her husband, Harold Nicolson. It ‘pleased Virginia because there could be absolutely no doubt as to which was the front and which the back’. It pleased her less a few days later. Virginia and Vita had bumped into Vanessa Bell in the street (she was wearing ‘her quiet black hat’) and gone with her to her husband Clive Bell’s house. ‘Clive suddenly said, or bawled rather, what an astonishing hat you’re wearing!’ Woolf wrote in her diary. ‘Then he asked where I got it. I pretended a mystery, tried to change the talk, was not allowed, & they pulled me down between them, like a hare; I never felt more humiliated.’ The next day, less upset, she noted, rather as she did about sitting for the sculpture, that she felt two things at once: ‘How I enjoy – or at heart how (for I was acutely unhappy & humiliated) these gyrations interest me.’

She was always anxious about buying clothes, and especially worried about what Clive Bell would find to say about them. In January 1935 she was ‘fluttered because I must lunch with Clive tomorrow in my new coat’. Before Bell it was her half-brother George Duckworth. Given an inadequate dress allowance by her father, Leslie Stephen, who spent the years after the death of his wife demanding sympathy and worrying about financial ruin, she’d had a dress made from green furnishing fabric. Duckworth ‘looked me up and down for a moment as if I were a horse brought into the show ring … I knew myself condemned from more points of view than I could then analyse … He said at last: “Go and tear it up.”’

In 1926 Vogue printed a photograph of Woolf wearing one of her mother’s dresses. It doesn’t fit very well. Julia Stephen herself had been much photographed by her aunt Julia Margaret Cameron, usually looking distant and melancholy. In all the pictures of Julia taken during Woolf’s childhood (she died when Virginia was 13), she looks thin and stern and much older than she was. One shows her on the veranda of their house in Cornwall, staring down at the plump Henry James, who is lounging on the steps reading. When Leslie Stephen died and the Stephen children escaped to independence in Bloomsbury, Vanessa hung Cameron’s photographs in the white-painted hall: great men – their father, Tennyson, Darwin, Browning, Meredith and the wild-haired astronomer Herschel − on one wall and her mother on the other. (The Hogarth Press, which Leonard and Virginia Woolf ran, would print a book of Cameron’s work accurately subtitled ‘Victorian Photographs of Famous Men and Fair Women’.)

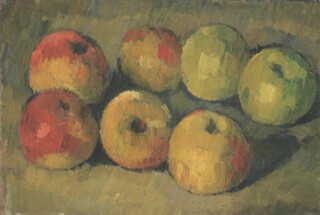

Woolf said that writing To the Lighthouse resolved her feelings about her parents; it ‘laid them in my mind’. The novel also considers her sister, or an aspect of her, in Lily Briscoe and her attempts to find the right structure for her painting, ‘that razor edge of balance between two opposite forces’. Watching and talking to Vanessa, Grant and Roger Fry, who organised the two exhibitions of 1910 and 1912 that introduced Post-Impressionism to Britain, had made Woolf think about the use of texture and form in her own work. In 1918 Maynard Keynes bought a small Cézanne still life from the sale of Degas’s collection in Paris. Woolf looked at the picture, and scrutinised the painters as they looked at it. ‘There are 6 apples in the Cézanne picture,’ she wrote in her diary (actually, there were seven).

What can 6 apples not be? I began to wonder. There’s their relationship to each other, & their colour, & their solidity. To Roger and Nessa, moreover, it was a far more intricate question than this. It was a question of pure paint or mixed; if pure which colour: emerald or viridian; & then the laying on of the paint … We carried it into the next room, & Lord! how it showed up the pictures there … the canvas of the others seemed scraped with a thin layer of rather cheap paint. The apples positively got redder & rounder & greener.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.