How many Maleviches were there? Though renowned as a pioneer of abstraction, especially for the stark geometry of his Suprematist canvases, Kazimir Malevich worked in many styles over the course of his career. The retrospective at Tate Modern (until 26 October), the most substantial in 25 years, is an unusual chance to see all his personae in one place, with more than three hundred paintings, drawings and architectural models from museums and private collections in a dozen countries. It must have been as much a diplomatic as a logistical feat: many legal wrangles over Malevich’s works have only recently been concluded – some canvases the Stedelijk acquired in 1958 are labelled ‘ownership recognised by agreement with the estate of Kazimir Malevich in 2008’ – which may be one reason the show is so comprehensive.

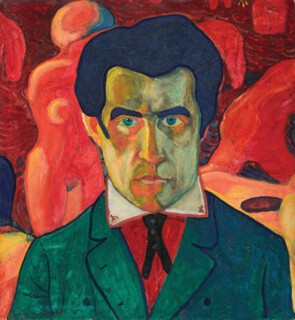

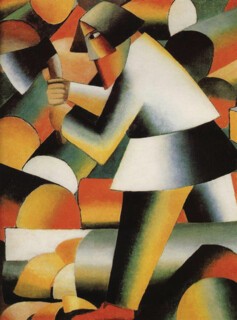

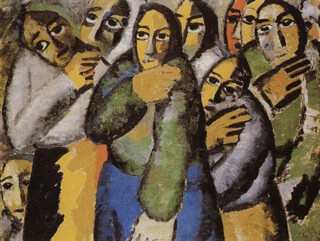

Born into a Polish family in Kiev in 1879, Malevich learned to paint in his teens, though nothing seems to remain from that time (so there is at least one Malevich we can’t now see). His first exhibition was in 1898 in Kursk, where he was working as a railway draughtsman, but the earliest piece on show here is a portrait of his father from 1902-03. On his first trip to Moscow in 1904, Malevich saw the Monets and Cézannes adorning the mansions of the wealthy merchants Ivan Morozov and Sergei Shchukin. In the years following, he made the journey from Post-Impressionism and Symbolism through Fauvism, primitivism and Cubism to abstraction, absorbing the lessons of each with a thoroughness that seems chameleonic: from the stippled clots of paint disclosing a Church (c.1905) to the Klimt-esque Shroud of Christ (1908); from the sensuous fluidity of the Self-Portrait (1908-10), which would recall Gauguin were it not for Malevich’s unmistakeable blunt stare, to the green-grey tones – Malevich later called it ‘Cézannism’ – of Landscape (1911). The succession of idioms is striking for its speed: months separate the folkloric primitivism of Floor Polishers (1911-12) and the Cubist dissection of space in Head of a Peasant Girl (1912). With The Woodcutter and Peasant Women in Church (both 1912), two phases share a canvas: on the front, the axe-bearing subject is broken into volumetric blocks, surrounded by curves and planes of colour; on the back, crudely formed faces and bodies crowd the frame, impoverished cousins of the Demoiselles d’Avignon.

The years 1913-15 brought a further acceleration, from an analytical Cubism to the radical breakthrough of Suprematism, revealed to the world in December 1915. At the 0,10 exhibition Malevich showed 39 paintings bearing only the simplest geometric forms against white backgrounds – Black Square (1915) the starkest of all. He himself saw it as the point of origin for his new system, calling it the ‘embryo of all possibilities’; he hung it in the top corner of the room, where Orthodox Russians traditionally place an icon. But X-rays reveal a more complicated composition beneath the cracked black surface, so Malevich’s purifying gesture clearly came after other experiments with geometric abstraction. At the time, Malevich dated his invention of Suprematism to 1913, which some took to mean he had hidden these shockingly denuded canvases away for two years. Yet the backdating is accurate if we take it to refer not to Suprematism itself, but to the germ of the idea. Malevich’s route there from Cubism is apparent in paintings and drawings from 1913-14. (Many of these rarely shown transitional works come from the collection of Nikolai Khardzhiev, a scholar of Futurism who emigrated to Holland in 1993 with sheaves of priceless papers in his suitcases.)

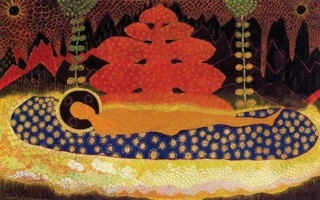

The possibility of paring down pictorial elements into abstract forms was latent in Cubism itself; but in Malevich’s case, the process received two further jolts. Both derived from his proximity to the poetic avant-garde – the ‘transrational’ verse of Aleksei Kruchenykh and others, who sought to break through to some higher meaning by returning to word-fragments and phonemes their original power. In illustrations Malevich made to accompany their compositions, letters or punctuation marks jostle with lines and shard-like shapes. The dissolution of established meanings was also behind the absurd juxtapositions of Malevich’s ‘alogist’ works, such as Cow and Violin (1913). In Lady at the Advertising Column (1914), floating signs appear among colourful geometric forms that clearly prophesy Suprematism.

There are premonitions, too, in Malevich’s designs for the avant-garde opera Victory over the Sun (1913). Here, much of the impulse towards abstraction paradoxically comes from reimagining the human form. The characters are themselves abstract – Enemy, Coward, Traveller – and Malevich correspondingly made costumes whose shapes and blocks of colour are more like the expression of internal traits than clothes. The Pallbearer’s torso is simply a black square, a pitiless nothing. Given the abstraction that was to come after, it’s easy to forget how close the geometric forms of Suprematism originally were to figuration.

Malevich billed Suprematism’s debut as the ‘Last Futurist Exhibition’, and wrote essays and pamphlets portraying it as the terminus of Western art. Yet the minimalism was far from barren – subsequent works grew ever more complex, with dynamic constellations of lines and planes in vivid colour floating on white backgrounds that suggest infinite space. There’s a sense of flight, of liberation into weightlessness. Although Suprematism predated the breakdown of the ancien régime, it’s no accident that Malevich’s revolutionary leap has been so closely associated with 1917. He played a prominent role in the new order, serving on several museum commission and education boards.

But in a sense, the Revolution only sharpened the dilemma Suprematism presented: where next? By 1918, Malevich had seemingly exhausted the possibilities of his new system, virtually erasing form altogether in the ‘White on White’ sequence. From 1919 (when he moved to Vitebsk for three years) to 1927, his main activity was teaching, and the exhibition includes some remarkable pedagogical wall charts. Suprematism appears, as before, as the culmination of Western art, but the bombast rings a little hollow – especially given his 1919 assertion that painting had died with the old order. In the first half of the 1920s, Malevich threw himself into making plaster mock-ups of Suprematist skyscrapers: the larger his ambitions, the smaller the outcome appears. The sense of infinite space is far stronger in drawings he made on scraps of paper during the Civil War.

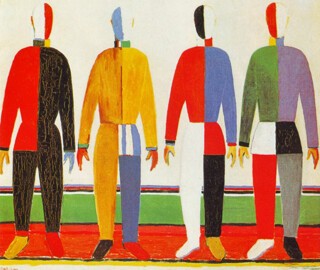

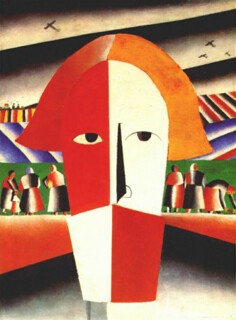

By the mid-1920s, the impasse was not purely aesthetic: officials and critics attacked abstraction as reactionary ‘formalism’, and in 1926 Malevich was dismissed from his post at Leningrad’s State Institute of Artistic Culture. A three-month trip to the West in 1927 didn’t produce the Bauhaus teaching job he had hoped for. On his return, Malevich began going over his entire oeuvre, ‘repainting’ early themes and backdating them – often seen as a clumsy attempt to bulk up his back catalogue with representational subjects. But Malevich’s turn to figuration was far weirder than the simple surrender to Stalinism it was once taken for. In the late works, different styles coexist, often within a single canvas. The blank, brightly coloured mannequins of Sportsmen (1930-31) and Woman with a Rake (1930-32) recall the designs for Victory over the Sun; there are echoes of his Cubist phase in the segmented faces and bodies of Carpenter and Head of a Peasant (both 1928-29); and a new motif, the landscape – the fields and plains of his youth? – appears as serried rows of colour marching to a low horizon.

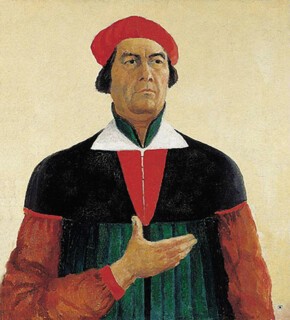

But if by the turn of the 1930s Malevich had found a way to deploy Suprematism’s forceful handling of colour and space on a human scale, the tone of his last works is altogether less stable. There’s an eerie combination of cheer and gloom in the 1933-35 portraits of his wife, the art critic Nikolai Punin and a female worker: each stands, dressed in red and white and blue, against a black backdrop, making enigmatic gestures with their hands. For his 1933 Self-Portrait, Malevich looks to have borrowed an outfit from the Quattrocento; he stands with one hand across his chest, again communicating something – but what? These final canvases suggest some private allegory or code at work, a kind of representation that suggests a mysterious absence. The Russian term for abstraction was ‘objectlessness’; what if the objects in figurative art bear no more relation to the physical world than geometric forms do, inhabiting some separate realm of their own? And what if the task of painting were not to depict, but to wall off one piece of that realm after another? After decades of bold pronouncements, Malevich’s work ended on a cryptic note, as if he had found a way to dress up abstraction as representation.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.