‘Proud’ is an epithet that extends from the parade to the workbench. The swagger of troops marching down the street is transferred by the carpenter to the nail that juts out, no less cocky, no less full of itself. There’s much in Tate Britain’s new exhibition, British Folk Art (until 31 August), that straddles both forms of pride. It opens with a fanfare of stout, galumphing tradesmen’s signs: the outsize models of boots, keys, teapots, top hats and so on that dangled over high streets two centuries ago. In the galleries beyond, weighty loads of colour are stitched or collaged onto banners, quilts and pictures in frames. The pigs and pigeons are very plump and each ship at sea is – as it were – ‘the good ship’, her sails unfurled and rigging immaculate. The show’s exultant centrepiece is a gallery painted marine blue in which figureheads redeemed from ship-breakers’ yards surge forward on all sides, dominated by a colossal moustachioed nawab carved in the Bombay Docks in 1831. A unicorn from Portsmouth, opposite it, must be the most manically aggressive equine ever invented. The woodcarver’s dreams of mastery and speed confer on the beast a muzzle of wild, pumped up muscularity: it’s a Bugatti for the age of sail. (It has been repainted who knows how many times since then, but surely the grace note of the lines drawn on the eyes follows the initial artist’s inspiration.)

Martin Myrone, one of the show’s curators, cautiously suggests that the figureheads, with their ‘chunky modelling’, ‘emphatic characterisation’ and ‘vernacular energy’, ‘might be considered as the exemplary form of folk art, construed as an aesthetic category’. ‘Cautiously’, because once you judge anything to be ‘folk art’, the discussion can snarl up in class-based knots. Folk is ‘them’, those not talking proper, not doing the judging: most typically, in this case, the artisans of imperial, industrialising Britain, a century or so either side of 1840. ‘Folk art’ enthusiasts can’t avoid this awkward speech position and, wisely, Myrone and his colleagues Ruth Kenny and Jeff McMillan don’t try to tidy it up. Rather, they let their eyes and curiosity take them on a ramble. If these lure them into an omnium gatherum – in one place, those Indian woodcarvers at work; in another, a French prisoner of war shaving mutton bones to construct a cockerel – well, they can cite contemporary museologists who dignify the effect as ‘polyphonic forms of chattering’.

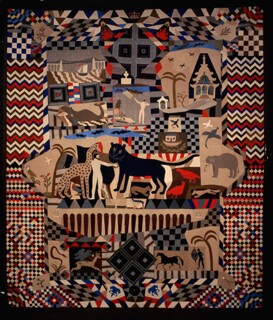

‘Chunky’ and ‘emphatic’ are Myrone’s stabs at giving folk art a formal – rather than a historical and social – character. But the effort winds you back to questions of what you can say from where. The masterpiece of the show is a very large quilt – some three metres long – completed by the Wrexham military tailor James Williams in 1852, after ten years’ stitching. It is a staggering feat of visual organisation, corralling thousands of offcuts of red, buff, black and blue regimental cloth into eye-dazzling rhythms underpinned by complex harmonies and punchily drawn imagery. Its thematic ambitions seem correspondingly large. Quilting, as the exhibition demonstrates, was a communal pastime in Victorian barracks and gun decks: another, even more vibrant example comes from the Crimean War, and a later photograph shows sailors gathered round sewing machines. Folk art here was a matter of ‘us’, males bonding over abstract or patriotic designs. Williams went beyond that. In his scheme, the four national symbols of the British Isles are upstaged by something like a résumé of human history, ranging through Adam, Cain, Noah and Jonah to Africa and China and the modernity of steam engines and viaducts.

‘Something like’, because whatever Williams might have wished to say was so broad that it baffles paraphrase. His quilt amazes rather than articulates, and for all that it’s a public piece, displayed at eisteddfodau, it stands as a monument to private obsession, rather like the concrete castle built by a retired eccentric in 1950s Hampshire, a film of which forms the show’s last exhibit. There was only so much you could communicate with this kind of art. The exhibition includes little that’s erotic, and less that’s pious. It shows British artisans celebrating their goods and their joint enterprises, or calibrating the workings of the social machine – as for instance in a painting of the country estate of Groombridge Place, one of several cartographic overviews. As an obverse to all this pride and positivity, there is wry, knowing banter – a satire on preachers, a saloon-wall scatology – passed around a more or less inclusive ‘us’. One such group, a group of two, Herbert Bellamy and Charlotte Springall, amused each other during the year before their marriage in 1891 by making a quilt loaded with in-jokes and fond mementos: another barrage destined to baffle.

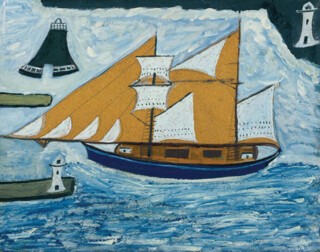

Britain’s so-called ‘liberal’ artists parted company with their artisan colleagues in 1768, when the Royal Academy was founded explicitly to put an end to exhibitions in which a Reynolds might rub shoulders with framed curios worked in worsted or in human hair. For all the subsequent backwards glancing in each direction, actual dialogue between the separated parties was intermittent. The story of Mary Linwood, famed for six decades from the 1780s for her stitched versions of Rembrandts and Gainsboroughs and then forgotten, intrigues the curators, but her regathered ‘needle-paintings’ are the most inert things in the exhibition. And there is the unschooled and exuberant Walter Greaves, who painted a boat race crowd on Hammersmith Bridge in 1862 but then succumbed to dreary Whistlerian sophistication.

The outstanding crossover came in 1928, when the modernists Ben Nicholson and Kit Wood latched onto the Cornish fisherman Alfred Wallis and his marvellous map-paintings (of which eight are on display), opening up a current of art-world curiosity about ‘the vernacular’ that swelled strongest in the years following World War Two. And now it has revived in the era of Grayson Perry and Jeremy Deller, of beards and nostalgic austerity: by 2014, this exhibition comes as an inevitability, and through our period spectacles, many of its quilts look fabulously contemporary – perhaps exactly because they’re so bold and so baffling. But there’s one question it allows you to forget: whatever happened to British folk art? It belonged to them, it seems, and it belonged to then.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.