Depending where you look, the William Burroughs centenary has either occasioned an outpouring of variously celebratory and carping prose, or a trickle of grudging acknowledgment in outlets thought to speak for the literary establishment. Writing on anything of passing public interest triggers an online avalanche of ad hominem posturing which quickly renders the original topic, whatever it was, numbingly opaque. The more exclusive realm in which people are paid for their opinions produces a similar effect, but with more concentrated ruthlessness and usually greater economy. Burroughs has been streaking across this ghastly spectrum since early February.

By now, anyone at all curious about Burroughs has absorbed a few interchangeable synopses of Barry Miles’s Call Me Burroughs – an exhaustive biography in every sense of ‘exhaust’ – along with boilerplate exegeses of the ‘cut-up’ and ‘fold-in’ methods; gleaned the current value of his stock in the literary market; and glazed over at the inexorable profusion of hip proper names attached like barnacles to the author of Naked Lunch. The cultic encrustations around Burroughs have done him the favour of keeping him current as a celebrity figure, but the disservice of implying that a home visit in old age from Kurt Cobain or a graveside serenade from Patti Smith has the same cultural importance as the writing of Nova Express and The Wild Boys. Burroughs’s actual achievement seems incidental to the glitzy mythologising of his remaining intimates, though still a bone of contention gnawed by literati.

Hardly anything worth reading twice about Burroughs’s writing, as distinct from his wildly chequered life and surprisingly genial personality, has appeared since Mary McCarthy’s New York Review essay on Naked Lunch in 1963. Negative reviews throughout his career consistently missed the point. Partisans continue to generate reams of ephemera about ‘language virus’ and other notions he gave apocalyptic weight to, but seem as prone to dubious traffic with the spirit world and magical thinking as Burroughs was himself; their prefaces, afterwords, blurbs and liner notes tend to evaporate in befuddling imitation of his oracular mode, without ever making clear what they’re talking about.

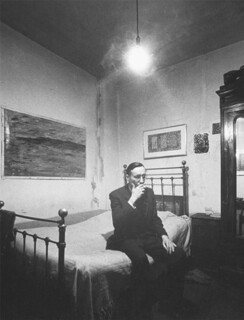

It doesn’t take a full-length biography to see that Burroughs found reality so intolerable that he spent much of his life escaping it, not only via drugs, but by serially immersing himself in otherworldly beliefs and pataphysical disciplines: black magic, Scientology auditing, orgone boxes, Whitley Strieber’s predatory sex aliens, sweat lodges and so forth. All these arcana yielded grains of incidental wisdom, along with a farrago of occult nonsense. They became storytelling gold, disposable platforms from which Burroughs issued torrents of Swiftian misanthropy in vignettes of atomic doom, mass extinction and the forcible mutation of tumescent teens into centipedes, machine parts or some kind of awful goo.

To a surprising extent, Burroughs relied on friends to structure his novels; they tidied up scattered riffs and routines lying around in piles of typewritten manuscript, assembled books from material discovered in long forgotten archives, moved sections from one book-in-progress to another. Allen Ginsberg selected the correspondence that became The Yage Letters. Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac put Naked Lunch together from drastic-looking clumps of torn, coffee-stained fragments; the book’s final sequence was determined by the order in which proof pages arrived back from the printer. Outtakes and overflow from Naked Lunch, supplemented by some of the cut-up experiments Burroughs adapted from Brion Gysin, became The Soft Machine, The Ticket That Exploded and Nova Express.

Burroughs’s use of chance and fortuitous accidents violated cherished notions of authorship, just as the horrifically explicit sexual metamorphoses in Naked Lunch and subsequent novels violated the codes of seemliness observed in literary fiction as well as the lubricious conventions of pornography. Widely overlooked in the shocked reception of Naked Lunch was its subversion of Anglo-American syntax, an excision of connective tissue that mimicked the scanning pattern induced by advertising. The trilogy that followed Naked Lunch went much further in anticipating the staccato, associative patterns produced by the internet, TV channel flipping and ‘screen reality’; considered unreadable when they were published, the trilogy books can be followed today almost as effortlessly as a novel by Hemingway.

Production of the early novels was often rushed; texts were revised after publication in one country while publication in another was held up by publishers’ financial calculations or ongoing censorship trials. As a result, several books exist in many versions, adding to the misleading impression that their contents were completely arbitrary. Burroughs oversaw the finished products, but when the chance occurred to improve them he decided he was comfortable with the idea of variants, viewing his overall production as a canon unto itself. No other American writers except Gertrude Stein and Henry James have managed this successfully, and I suspect it’s a further source of irritation to those who find Burroughs irritating anyway.

He was a rare example – Faulkner was another – of a writer who can write while intoxicated and he wrote nearly everything stoned on weed or on the nod. Seriously medicated, he was far from oblivious. After every ordeal of heroin withdrawal Burroughs confronted the horrific reality of ‘the naked lunch at the end of the newspaper fork’ and it gradually pulled his great metaphor of control into focus: the social order controls its subjects by addicting them to drugs, money, sexual desire, consumer products and technology; to habit, insensible codes of morality and binary logic; and by reproducing the species in gendered bodies on a planet of incompatible life forms.

Burroughs’s singular clarity on this subject never immunised him against narcotics. The apomorphine cure he took in Britain, touted in Junky as his final release from hell, was in reality short-lived, but it persisted as an article of faith in the legend spun around him. When, around 1980, he slipped into permanent relapse (which, after moving to Kansas from New York, he managed to regulate by switching to legal methadone), it remained hush-hush until after his death.

The secrecy was prudent. Even though his recurring habit has little bearing on any serious consideration of his work, and could hardly have disillusioned his followers (most of whom knew about it anyway), his detractors would probably have used it to trash his later books. To an ever vigilant, gatekeeping mentality, what McCarthy identified as the ‘high, aerial point of view’ of Burroughs’s fiction – with its carnivalesque exhibition of human grotesques, science fiction mutations, talking assholes, sex acrobats, blithely murderous surgeons, rampaging purple-assed baboons and redneck Southern sheriffs – was the delirious product of a drug-addled mind, with no legitimate implications or importance as social commentary.

McCarthy perceived in Naked Lunch, Grass’s The Tin Drum and Nabokov’s Lolita and Pale Fire ‘a new kind of novel, based on statelessness … with a plot of perpetual motion’. She welcomed the novel’s demolition of sclerotic 19th-century forms and its fragmented mirroring of consciousness in the age of mass media, rapid international travel and global cultural homogenisation. A handful of American writers have accomplished something original with the novel form in his wake – John Hawkes, Rudolph Wurlitzer, Renata Adler, Lynne Tillman, Kathy Acker, Bret Easton Ellis and Tao Lin come to mind – but innovative narrative fiction has enjoyed far greater support from publishers and readers in Europe. The bulk of published American fiction consists of cookie-cutter, middle-class ‘problem novels’ by tenured academics and their MFA spawn, Dickensian verisimilitude courtesy of Wikipedia (cf Rachel Kushner, Jonathan Safran Foer et al).

Something of this retrograde motion warps American criticism as well. Even today, when subjects Burroughs treated long before anyone else – the surveillance state, the technological engineering of consciousness, planetary extinction – have become urgent global concerns, a critic like Peter Schjeldahl in the New Yorker, presumably speaking for a politburo, can still assure his readers that Burroughs ‘wages literary war not on perceptible real-world targets but against suggestions that anyone is responsible for anything’ and that a writer whose singular, crackling cadences are audible in every line he wrote ‘had no voice of his own’.

In Miles’s biography – but also in Burroughs’s accounts of himself – it’s readily acknowledged that for much of his life, Burroughs evaded onerous personal responsibilities, as most addicts do: primarily with respect to his son Billy, who pathetically aped his father’s protean drug and alcohol consumption, hoping to win his approval, and ended up dying of cirrhosis at 33. Burroughs repeatedly had other people bail him out of trouble with the law, and drew a generous allowance from dismayed but dutifully supportive parents until the age of fifty; before Naked Lunch brought him fame and notoriety he led a motile existence, swept from place to place on prevailing currents of la vie bohème and the availability of drugs; at various times he engaged in petty crime, including rolling subway drunks for H money. But it doesn’t follow at all that his books incite readers to emulate him. His autobiographical writings are consistently, emphatically cautionary tales. (‘Everyone is responsible for his or her own actions – everything they do,’ he wrote in his final journals, quoting Mario Puzo. It was hardly a volte-face.)

I have yet to discover a single account of Burroughs in which people who knew him fail to mention his impeccable manners, his kindness, his generosity; they invariably refer to him as ‘a true gentleman’. The radically anti-authoritarian, left-libertarian notions he espoused probably look like irresponsible nihilism (or ‘antinomian morality’, in Schjeldahl’s solecism) to many of those ensconced at their computer screens during most of their waking life, or bedazzled by mobiles and ubiquitous electronic signage in a society overloaded with information yet drained of authentic experience. It now seems almost logical that the insight Burroughs offers into the brain-scrambling technical synaesthesia spreading everywhere would be precisely what brands him a crackpot, rather than the silly religions and fatuous disciplines he so often became fascinated by. Still, I feel it’s necessary to say how stupid this inverted logic is.

On social media legions of isolated individuals, with the brainless malice of a concierge, spread ‘the real dirt’ on artists, writers, actors, musicians, athletes and others in the public eye. A tsunami of ugly feelings surges across the global clothesline at the mere mention of ‘Woody Allen’ or ‘Roman Polanski’ in the press; Burroughs, too, has an anti-claque of Torquemada wannabes, enraged over his accidental shooting of his wife in 1951. Social media can launch a witch hunt or pogrom just as readily as a ‘progressive’ uprising, and in either instance directs the madness of crowds to unexamined targets of outrage; the technology itself is probably as addictive as heroin, since it acts directly on neural synapses, and its instantaneous transmission eliminates any space for reflection or analysis between emotional impulse and action. Burroughs mapped this territory before it existed in anything like its present form:

The virus attack is primarily directed against affective animal life – Virus of rage hate fear ugliness swirling round you waiting for a point of intersection and once in immediately perpetrates in your name some ugly noxious or disgusting act sharply photographed and recorded becomes now part of the virus sheets constantly presented and represented before your mind screen to produce more virus word and image around and around it’s all around you the invisible hail of bring down word and image –

He seems to have lived in the future from an early age, an effect of social exclusion that was the standard lot of children who are both precocious and gay everywhere in America until recently, and probably still is outside certain major cities. Miles’s account of Burroughs’s childhood and adolescence is the last word we’ll need about this period. What’s most striking are descriptions of people and events that are woven through Burroughs’s work as unexplained but strangely recognisable ectoplasms from childhood. His late books are suffused with feeling, melancholia especially, but his early writing is generally considered satirically aloof and cold-blooded, and the lavishly detailed episodes in Miles’s book reveal unsuspected emotional depths encoded in the cybernetic-looking prose of works like The Soft Machine and The Ticket That Exploded.

‘As a young child I wanted to be a writer because writers were rich and famous. They lounged around Singapore and Rangoon smoking opium in a yellow pongee silk suit,’ he wrote in a 1970s essay called ‘The Name Is Burroughs’, conjuring an image identical to one that Ernie Kovacs, sending up Somerset Maugham, incarnated in his 1950s TV sketch show. Almost half of Call Me Burroughs, however, takes place before Burroughs seriously tried to write anything – his first real effort didn’t occur until he began Junky in 1950, at the age of 36.

The late start isn’t that surprising: the Burroughs we later see going to Harvard and vacationing in Europe with friends, then consorting with the junkie dregs of Times Square and Upper Broadway and playing wise uncle to the much younger Ginsberg and Kerouac at Columbia, had crippling insecurities about his ability as well as his sexual identity, and felt like a perpetual outsider, unable to connect even with his closest friends. Deeply abject, clueless about intimacy, he made do with female prostitutes while conceiving unrequited, drama-fraught attachments to male hustlers who were basically straight, at one point slicing off a fingertip over one of them, in imitation of Van Gogh. He spent years in and out of psychiatrists’ offices and psychiatric wards. During the Columbia period, while the other core members of the Beat Generation were discovering mary jane and Benzedrine, he discovered junk, courtesy of scumbag Herbert Huncke. At around this time he married Joan Vollmer, and in somewhat honorary fashion assumed the role of family man for five years.

Call Me Burroughs has an epic plenitude that makes the idea of repotting it in miniature especially unappealing. I think it’s enough to say that Burroughs got a first-rate classical education; had many spells of marginal employment (exterminator, detective, advertising apprentice, West Texas cotton farmer); studied medicine briefly in Vienna; married a Jewish woman he met in Yugoslavia to get her out of Europe ahead of the Nazis; got arrested and jailed for drug possession and trafficking several times and remanded on one occasion to the United States Narcotic Farm in Lexington, Kentucky; undertook perilous journeys in Ecuador, Peru and Colombia in search of the ‘telepathy drug’ yagé; later went to North Africa, lived all over the place and took every drug known to man and pharmacist; and had his important turning point after committing involuntary homicide. After a brief incarceration in Mexico, his life resumed its vagabond pattern for several years; then he published one of the most important novels of the 20th century, and everything was suddenly different except the drugs, which tended to make everything that was suddenly different somewhat the same thing as before.

In many writers’ biographies, the watershed moment of the first book’s publication is a wet dream that comes early and dries up fast. The writer’s life is changed overnight; never again will he or she meet the sort of people from before, and the next five or six decades will be nothing but horrible dinner parties and messy divorces. Carrying oneself around as a figure becomes in many ways one’s total raison d’être. Without the specious exemption from the rest of humanity fame bestows one is nothing at all. It doesn’t make for an exciting life and isn’t much fun to read about, either.

Burroughs has to have been among the last American novelists to have lived an entire, real life before becoming a writer, in the sense that Melville, Jack London and Poe had real lives, and spent years of utter anonymity among individuals unlike themselves, in many layers of the class system, knew one great love and many not so great ones, and understood the world around them from the ground up before setting pen to paper in earnest. This used to be an expected trajectory for American novelists: even if the realm available to them was circumscribed, they knew almost everything about it and the people in it by the time they decided to write, and they figured out the rest in the act of writing.

They were read because they knew about things their readers didn’t, had ventured further into the physical world or the human heart, had risked their lives or their sanity to bring back something worth telling about. Or they studied the laughter in the next room with the patience and cunning of a cat, and played it back in language that enabled you to see through the wall who was laughing, and why. It wasn’t a profession you could train for in a classroom – not because writing can’t be taught, but because experience can’t be taught. (It can’t be faked, either, though plenty of fake novels get published every year, and even succeed in a fake way.)

Yet it’s a fact that Burroughs, one of the very few American novelists of the last fifty years who actually matters, has had a negligible influence on ‘mainstream’ American literature, while his effect on popular culture has been incalculable. It may be comforting to some arbiters of aesthetic fashion to write Burroughs off as a perennial enthusiasm of ‘the young’, but they might consider that several generations of these young have since occupied key positions in film, TV, the recording business and advertising, to cite only four sectors of the consciousness industry that seem far more familiar with our internal wiring than the current literary world, which becomes ever more parochial and conservative as its importance in the culture shrinks.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.