It started with the jitterbug, or with a ketchup bottle. Kathleen Maddox couldn’t get away with dancing in her hometown. Ashland, Kentucky in 1934 was too small, and if she let a boy hold her hand word would always get back to her mother Nancy, a strict Christian widow. But across the river was Ironton, Ohio, and there she could dance at a club called Ritzy Ray’s. That might have been the place she met Colonel Scott, a small-time local con artist who made his dimes collecting tolls from drivers crossing a free bridge. When Kathleen got pregnant, Scott told her he’d been summoned away on military business. In fact, he was a civilian (Colonel was his given name) and a married man. Kathleen gave up waiting for him and found a husband, William Manson, employee of a local dry cleaner. They moved to Cincinnati. She named the baby after her dead father, Charles. She was 16.

And she was still a bit wild. She kept going out most nights, and after three years William divorced her for ‘gross neglect of duty’. She filed a bastardy suit against Scott, and won $5 a month in child support. She got $25 on her day in court, and that was all. She and her brother Luther were now in the habit of driving to Chicago, where Kathleen would flirt with men in bars and lure them out into the street so that Luther could beat them up and take their money. They tried it closer to home at least once. On 1 August 1939 Kathleen and her friend Julia Vickers met Frank Martin, who took them driving around Charleston, West Virginia in his grey Packard convertible. At Valley Bell Dairy he bought them cheese, and at Dan’s Beer Parlor he got them pints. Kathleen said they ought to rent a room somewhere; it would cost $4.50. Martin put down three dollar bills and a couple of quarters to show he was willing. Kathleen called Luther from a pay phone. They picked him up at a petrol station and went to another beer hall, where Vickers stayed behind. Back on the road, Luther told Martin to stop the car, and they got out. Luther had a ketchup bottle full of salt. He stuck it in Martin’s back and told him it was a gun. Martin was not convinced, so Luther knocked him over the head. Brother and sister got away with the car and $27. They were arrested the next day. Nobody in the family was ever good at not getting caught.

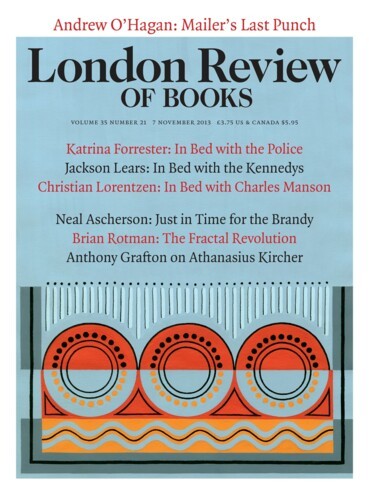

‘It was an impetuous decision,’ Jeff Guinn, a Texan journalist, writes, ‘that would affect – and cost – lives over the next three-quarters of a century.’ Somewhat portentous, but not wrong. Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson is a cradle-to-grave treatment, though the graves belong to other people. The subject remains in California, an inmate at Corcoran State Prison, where he issues statements his followers disseminate via the website of his Air Trees Water Animals organisation. A recent example: ‘We have two worlds that have been conquested by the military of the revolution. The revolution belongs to George Washington, the Russians, the Chinese. But before that, there is Manson. I have 17 years before China. I can’t explain that to where you can understand it.’ Neither can I. Guinn explains a lot in his usefully linear book. The standard Manson text, Helter Skelter, the 1974 bestseller by his prosecutor, Vincent Bugliosi, and true-crime writer Curt Gentry, is a police and courtroom procedural, with no shortage of first-person heroics (‘During my cross-examination of these witnesses, I scored a number of significant points’); the first corpse is discovered on page six. No one is murdered in Guinn’s book until page 232. He brings a logic of cause and effect to the madness.

The Ketchup Bottle Holdup was the point where the five-year-old Manson’s life veered from hard luck to horror show. His mother and uncle went to prison in Moundsville, West Virginia. He was taken in by his aunt Glenna, in nearby McMechen, where his uncle Bill was a railroad engineer. On the boy’s first day at school, his teacher humiliated him and he ran home crying. His uncle wouldn’t stand for such sissyish behaviour, and sent him back the next day in a dress of his cousin Jo Ann’s to teach him a lesson. Jo Ann (not her real name) is one of Guinn’s sources, and she relates tales of the boy’s constant lying, his attempts to attack her with a sickle and later to steal her father’s gun, and his talent as a piano player and singer of hymns. He was a charmer, but also selfish and disloyal, a whiner and a snitch. Kathleen was paroled after three years and took her son back to Charleston. She married a circus hand she met at an AA meeting, though neither of them quit drinking, and he kept at it heavily. They drifted to Indianapolis. The boy’s truancy and shoplifting put a strain on the marriage, so Kathleen decided to send him to a Catholic school for delinquents. A psychological examination found he had ‘a tendency toward moodiness and a persecution complex’. He ran away, was caught robbing a store, and was sent to Boys Town in Omaha. The subject of a 1938 Spencer Tracy movie, it had a reputation for turning troublemakers into nice young men, and was the gentlest place he could have hoped for. But after four days, he and a boy called Blackie Nelson broke out, stole a car, got hold of a gun, robbed a grocery store and a casino, and headed for Peoria.

There the pair became apprentices to Nelson’s uncle, a professional thief. But within two weeks Manson was caught robbing an office, and sent to a tough reform school in Plainville, Indiana. Punishments included whippings with paddles, ‘duck walking (staggering painfully about with hands clasping ankles) and table bending (arching backward with shoulder blades barely touching the surface of a table; just holding the position for a few moments ensured that a boy could not walk normally for hours afterward).’ He was 13 years old and a runt: he later claimed that a staff member encouraged other students to rape him, a claim the sceptical Guinn credits. His method of fending off aggressors was to play the ‘insane game’, screeching and flapping his arms. He tried to escape at least six times, and made it out twice: the first time in a mass breakout that ended for Manson when he was caught robbing an Indianapolis petrol station; the second time, now 16, he was stopped in a stolen car at a roadblock in Utah. Crossing state lines made it a federal rap, and it landed him at the National Training School for Boys in Washington, DC. His IQ was found to be above average (109), and he was judged to be ‘aggressively anti-social, at least in part because of “an unfavourable family life, if it can be called family life at all”’. A psychologist who examined him wrote: ‘One is left with the feeling that behind all this lies an extremely sensitive boy who has not yet given up in terms of securing some kind of love and affection from the world.’ Guinn takes this as an instance of Manson conning his way into a transfer to a cushier (less brutal) institution. He got it, as well as a scheduled parole hearing. But a month before the hearing he was found raping another boy while holding a razor to his throat. He was moved to a maximum security institution. His wardens now believed that he was ‘criminally sophisticated’ and ‘shouldn’t be trusted across the street’. A further reversal in behaviour persuaded them to let him out two years before his release was required. He was 19.

He went back to McMechen to live with his aunt and uncle. He was ostracised by the clean-cut town youth, who saw him as a degenerate freak when he bragged about his crimes and about ‘shooting up’ in the clink. He was somebody people found repulsive or irresistible. A railroad man called Cowboy Willis took a shine to him and introduced him to his daughter Rosalie. ‘It was an unlikely romance,’ Guinn writes, ‘between a cute popular girl and the town pariah.’ They married, Manson bought his first guitar, and he worked at a racetrack sweeping out stables. On Sundays he went to church with his grandmother. Rosalie was soon pregnant, and the bills started to be a strain. Stealing cars was Manson’s solution, but he had to do it across the river in Ohio to avoid reprisals from the local mob. And he was growing restless. His mother and her husband had moved to California. He wanted to join them. He stole a Mercury, and took his wife to LA.

He kept driving the car when he got there, and a cop spotted the Ohio licence plate. Manson pleaded that living in the outside world confused him, and admitted that he’d stolen another car and taken it to Florida. A psychiatrist determined that ‘with the incentive of a wife and probable fatherhood, it is possible that he might be able to straighten himself out.’ If he had only shown up for his next hearing, he probably would have been given five years’ probation. Instead he and Rosalie skipped town for Indianapolis, where he was booked. He was sentenced to three years at Terminal Island Penitentiary in Los Angeles Harbour. After a few months Rosalie divorced him and went back to Appalachia with another man and the newborn Charlie Jr. (She died of lung cancer in 2009; her son committed suicide in 1993.) Twelve days before a parole hearing Manson was caught trying to hotwire a car in the prison parking lot. He took another IQ test and scored 121. He could barely read or write, but he was clever in his way. The inmates who fascinated him were the pimps. He wanted to learn their trade. It was his first flicker of ambition. He enrolled in a fashionable prison course on the teachings of Dale Carnegie, the author of How to Win Friends and Influence People. ‘Let the other fellow feel that the idea is his’ would become an essential part of his repertoire as a cult leader.

On the outside he tried to make a go of it as a pimp, but after seven months, he was caught again trying to cash a forged US Treasury cheque for $37.50 at a supermarket. As federal agents questioned him about it, he swallowed the cheque. One of his prostitutes, Leona Rae Musser, got him off by claiming she was pregnant with his child. She wasn’t, but they married. Then she was. He skipped town, and she testified against him. (She divorced him, and nothing is known of their son, Charles Luther.) He got a ten-year sentence. In 1961, he entered the federal prison on McNeil Island in Puget Sound, where he discovered Scientology, read Robert Heinlein’s science fiction novel Stranger in a Strange Land, and first heard the Beatles. From Scientology, he took ideas that he would combine with Carnegie’s: let the other fellow think he was an immortal spiritual being; exploit his traumatic experiences. He seized on Heinlein’s anti-government paranoia and his concept of group sex as a sort of sacrament. The last element of what Guinn calls his ‘beguiling, hybrid pseudophilosophy’ was his own destiny as a pop star who would be bigger than the Beatles. He practised constantly on his guitar and wrote songs. In this respect at least, though rather old, he wasn’t very different from a lot of American teenage boys. His musicianship was less than average.

He panicked a little before his parole in March 1967. ‘He has no plans for release as he says he has nowhere to go,’ his last prison report stated. He received permission to go from Los Angeles to visit another former inmate in Berkeley. He’d stepped from the 1950s into the Summer of Love. Guinn takes a dim view of hippies (dirty), cops (incompetent) and celebrities (craven). His San Francisco is a nightmare of bad sanitation, methedrine, heroin and rape. The atmosphere was congenial enough for Manson, now 32 years old and an aspiring singer-songwriter. He saw that being a guru had more growth potential than pimping – a different proposition in an age of free love. His first follower was Mary Brunner, a lonely 23-year-old assistant librarian at Berkeley; she took him in and initiated him into environmentalism (a cause he still advocates, in his way). The second was Lynette Fromme, an 18-year-old runaway he found on a trip to Venice Beach. ‘The way out of a room is not through the door,’ he told her, ‘just don’t want out, and you’re free.’ When he walked away, she followed.

A recruitment phase began. The women were mostly from broken down middle-class families. Manson told them they were beautiful and nothing was their fault. The message was to do away with guilt and shame, with the ego, with worldly possessions, with the hang-ups of the outside world. He would fill the void. He started saying he was the Second Coming. He needed money and a way to get around. A minister called Dean Moorehouse picked him up hitchhiking and brought him home. Manson persuaded Moorehouse to give him the family piano, which he dragged down the street and traded for an old Volkswagen minibus. He drove off, taking Moorehouse’s teenage daughter Ruth Ann with him. Her mother called the police, who caught them but not before Manson had made a convert of her. He told her to marry someone, which would legally free her from her parents, and then find him. On a trip to Los Angeles, he picked up Patricia Krenwinkel, whose father paid the monthly bills on her Chevron credit card: gas money. ‘For the very first time in my life,’ she wrote home, ‘I’ve found contentment and inner peace.’ Manson and the three women were panhandling and freeloading and eating from bins in the autumn of 1967 when Manson recruited the topless dancer Susan Atkins in Haight-Ashbury. Unlike the others, Atkins ‘looked good’ and wasn’t shy. Manson told her ‘she needed to imagine she was making love to her father.’ Sex would be the means of recruiting male followers, as well as obtaining food, shelter and the attention of men with ties to the recording industry. They traded the minivan for a school bus they painted black. The Family went to LA.

Stardom, he told them, would be the way to share his teachings and their love with the world. It was a dream that kept them motivated when it was hard to find food, when there was no place to shower, when they had to sleep in the bus or with strangers, or when Manson imposed discipline by pulling their hair or hitting them. They had hope. The first opportunity was with Gary Stromberg of Universal Music. Manson had his number from a fellow inmate. Stromberg booked a three-hour studio session for him: ‘an unmitigated disaster’, according to Guinn. ‘I ain’t used to a lot of people,’ Manson said. But Stromberg liked him, and was impressed with the way he could order the women around. Universal was considering making a film about Christ coming back to America, and he discussed it with Manson, who said Jesus should be black and the Romans Southern rednecks. It was a little too much for the suits. Stromberg told him to work harder on his songs.

He moved the Family to a house in Topanga Canyon. Their numbers were climbing, to around twenty – including a few male members who were vying for the role of Manson’s second in command – by the spring of 1968. Some female initiates were rejected because Manson deemed them insufficiently vulnerable or sexually compliant. (The bar was lower for men.) Others, like Angela Lansbury’s daughter Didi, were kept around because they were a ready source of cash, and then let go when it ran out or their credit cards were cut off. There were competing gurus (anarchists, Buddhists, Satanists etc) in Topanga, so Manson took the Family on long road trips across the South-West in the school bus, apeing the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour. Otherwise the daily routine consisted of a perfunctory breakfast of leftovers; morning work for the men on cars and motorcycles lent or given to the Family; foraging in grocery store bins for the women; afternoon orgies; group dosings of LSD (Manson tended to give himself a lower dose); dinners where Manson performed his own songs and those of the Beatles on his guitar. Everybody got a nickname. Nobody was allowed to drink alcohol; eat meat; keep wristwatches, clocks or calendars; read books besides the Bible; wear glasses; or use birth control. They called the first child Pooh Bear.

Their next relocation made it seem as if Manson’s predictions were coming true. Dennis Wilson picked up Krenwinkel and another Family woman hitchhiking and offered to take them home in his Ferrari for milk and cookies. When Manson heard they’d been to a Beach Boy’s house, he demanded they take him there, along with everybody else. The drummer was not at home, so they settled in for a party. The drummer pulled up after midnight, and Manson greeted him. ‘Are you going to kill me?’ Wilson asked. ‘Do I look like I am?’ Manson kissed his feet. Wilson let the Family stay in his log cabin on Sunset Boulevard for the rest of the summer, fed them, and tried to help Manson with his music. Manson listened to Wilson talk about his abusive father, and provided him with a harem. Wilson called Manson ‘the Wizard’. But Wilson’s efforts to sign him to the Beach Boys’ Brother Records went nowhere, and a session at his brother Brian’s home studio was another debacle (‘This guy is psychotic,’ the engineer said; he was also filthy and foul-smelling). There was another close call with Neil Young, who came by the cabin one day and played with Manson. The Byrds’ producer Terry Melcher, son of Doris Day, was often at the house. He wanted to bring Ruth Ann Moorehouse home as his maid; his girlfriend, Candice Bergen, wouldn’t have it. Towards the end of summer the Beach Boys went on tour, and when Wilson returned he learned that $800 had been charged in his name at Alta Dena Dairy. Counting a totalled Mercedes, the Family’s freeloading that summer had cost him $100,000. He shied away from a confrontation, sneaked off to a small apartment, and let his landlord evict the Family when his lease on the log cabin ran out.

They moved to the Spahn ranch, on hundreds of acres 35 miles north-west of downtown LA, full of hills, streams, caves and the disused sets of 1950s westerns and television shows. George Spahn, the octogenarian owner of the property, was offered Fromme as a housekeeper and concubine (her reactions to his pinches got her the name Squeaky). A change of scene always reinvigorated the Family, and living on a movie set was fun. ‘It was Halloween every day,’ Krenwinkel said. But boredom always threatened, and why didn’t Jesus Christ have a record contract yet? To compensate, Manson’s pronouncements became more apocalyptic when the Beatles’ White Album came out at the end of 1968. Its songs contained prophetic codes about a coming race war (called ‘Helter Skelter’): the blacks would rise up and enslave the white pigs; the Family would wait out the carnage in a city underneath the desert in Death Valley, where they could assume new forms and grow in number to 144,000; then they would emerge to rule the world, which the blacks would gladly hand over, having found they weren’t up to the task. (Until now Manson usually hid his racism from the women.) Preparations ensued. A ranch in Death Valley belonging to a Family member’s grandmother would be the base from which they would search for the hole that would lead to the underground city (where the Beatles would join them). An arsenal of knives and guns was accumulated. Cars were stolen and refurbished as dune buggies.

On 19 April police looking for stolen cars raided the Spahn ranch, arrested several of the Family – though not the absent Manson – and impounded some dune buggies. The arrests didn’t stick, but Manson’s paranoia was heightened. He warned the Family that if he was arrested they should expect him to act crazy: the insane game again. There were two more musical disappointments: Wilson recorded a song for the Beach Boys with lyrics by Manson as the B-side of a single, but he’d changed the title and some of the words, kept the songwriting credit for himself, and the single was a dud. Melcher came to the ranch twice. The second time the man recording the audition was slipped a tab of acid and suffered a bad trip, and Manson beat up another drunk visitor. There would be no record contract.

The embarrassment made Manson desperate and his rage harder to conceal. He said he’d been betrayed by Melcher and Wilson the way Jesus had been in the Bible. He ratcheted up the end-times rhetoric: the Helter Skelter race war was ‘coming down fast’. But control was ever harder to maintain among the now three dozen Family members, and a wave of defections started. Money was also scarce, and a lot of it would be needed for provisions on the move to Death Valley. Manson tried to swindle a drug dealer called Lotsapoppa, who claimed to be a member of the Black Panthers. Manson shot him in the chest, left him for dead, and got away with the money. But his new fear was of Panther reprisals. (In fact, the wound had not been fatal, and Lotsapoppa wasn’t really a Panther.) The Spahn ranch was essentially militarised, with armed Family members on guard duty around the clock (except there were no clocks).

Manson never got the chaos he wanted. He tried three times, but he couldn’t light the fuse. His friend Bobby Beausoleil, a star of Kenneth Anger’s short film Lucifer Rising, was in a fix with a biker gang after selling them $1000 worth of tainted mescaline. Manson offered him back-up to recover the money from his dealer, Gary Hinman; they would take Hinman’s Fiat and Volkswagen bus and whatever else they could get for the Family. Hinman let them have the vehicles, but throughout a weekend of beatings – Manson showed up to slash his ear with a sword – Hinman insisted he had nothing more to give, and would call the police when his attackers left. Manson, who worried any police scrutiny would uncover his murder of Lotsapoppa and send him to jail for life, told Beausoleil to kill Hinman and make it look like the work of the Panthers. He did, and fled north in the Fiat but it broke down outside San Luis Obispo. Passing high-way patrolmen ran a check on the vehicle and found an alert connecting it to the murder. The bloody knife was in the tyre well.

Beausoleil’s arrest threatened to bring the law down on the Spahn ranch. By the logic of paranoia, there seemed to be two options: break him out of jail, or commit copycat murders that would both persuade the authorities to free him (because the real killers were still at large) and unleash the racial frenzy Manson had been predicting all year. In other words, the way to escape a murder rap was to commit further, essentially random murders. By this point, in Guinn’s account, Manson was the captive of his own bullshit:

He’d hoped that the police would think that the paw print and words ‘political piggy’ scrawled on Gary Hinman’s walls with Hinman’s own blood were proof that the Black Panthers had committed the murder. If the cops and the media had made enough out of it, that might have initiated white reprisals, black retaliation, and then Helter Skelter – if not an apocalyptic race war, then at least local violence between the races, sufficient bloodshed to impress upon the Family that Charlie had the power to bring about cataclysmic events. But it didn’t happen that way, perhaps because Hinman wasn’t important enough. The concept was still valid. The victim or victims just had to be more prominent.

The target was chosen because it was Melcher’s old residence on Cielo Drive: the one place Manson was sure famous people were living. Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate had just rented the house. Polanski was abroad. The pregnant Tate had appeared in Valley of the Dolls and Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers but was hardly a celebrity. She was having a quiet night at home with friends: her ex-fiancé, ‘internationally known men’s hair stylist’ Jay Sebring; the coffee heiress Abigail Folger; and Folger’s boyfriend. They were all murdered, as was a local teenager who’d stopped by and was on his way out. Manson sent four Family members to do the job, led by Charles ‘Tex’ Watson. They were high on speed and armed with knives and a single .22 pistol. Tate was the last to die; she begged them to take her with them and kill her only after her baby was born. Watson stabbed her to death and Atkins wrote pig on the front door with her blood. They returned to the ranch, and Manson went to Cielo Drive in the early morning to vet their work. He wiped off fingerprints, made the crime scene look more theatrical by draping an American flag over the sofa by Tate’s corpse, and left a false clue: a pair of glasses (no Family member could have been wearing them). The next day he deemed the press reaction insufficient: there had to be another killing. Grocery chain owner Leno LaBianca and his wife Rosemary were ordinary people unlucky enough to live on a street where the Family had once been to a party. ‘HELTER SKELTER’ was written in blood on their refrigerator.

The trial gave Manson what he’d always wanted: he was famous, with his picture on the cover of Rolling Stone and a national platform for the insane game. Other murders were committed and attempted by the Family: most famously in 1975 when Squeaky Fromme, dressed in a red nun’s habit, stepped out of a crowd, aimed a .45 at Gerald Ford, and was tackled by Secret Service officers. The story lingers and books like Guinn’s are written to remind the Baby Boomers why they cut their hair and switched from hallucinogens to anti-depressants. The Family members who aren’t dead or out of sight are born-again Christians. Manson now sends sketches and statements to the keepers of his online flame. He remains a vegetarian and a subscriber to National Geographic. He occasionally puts on a show at on-camera parole hearings. You can watch them on YouTube: ‘Is this going in the history books?’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.