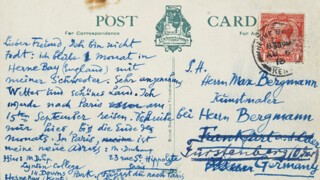

‘I am not dead; I am in Herne Bay,’ Marcel Duchamp wrote to the painter Max Bergmann in August 1913. If you know the north Kent resort today – its decayed seafront and sad amusements – Duchamp’s presence there may seem absurd, his reassurance not entirely convincing. But the postcard he sent Bergmann shows the town in its prime: a place lately promoted from a staging post en route to Margate, with its radial streets confected as a genteel alternative to more garish pleasures along the coast. The tinted photograph shows a chilly shingle beach but an elegant parade, and was taken from Herne Bay’s pier; at 3787 feet, it was then the second-longest in England after the one in Southend. In 1910, the Grand Pier Pavilion was built on its end, and there was music, dancing and skating to divert promenaders – among them many language students from across the Channel.

In the summer of 1913, Duchamp, then aged 26, was depressed and somewhat uncertain as to his next artistic move. In 1912, his Nude Descending a Staircase had been rejected by the hanging committee of the Salon des Indépendants in Paris; when the painting appeared in New York at the Armory Show the next year, the New York Times declared it ‘an explosion in a shingle factory’. It seemed he had a succès de scandale on his hands, but he wasn’t yet ready to make good on it. He wouldn’t become the ‘inventor’ of the readymade until 1915, and although he had made notes and drawings all summer for the work that would become The Large Glass (or The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even), the project remained ‘definitively unfinished’. In July he wrote to Walter Pach, who had organised the Armory Show: ‘I am very down at the moment and doing absolutely nothing. It’s very irritating when it’s like this. I am going away in August to spend some time in England.’

Details about Duchamp’s time in Kent are scarce. We know that he travelled as chaperon to his 17-year-old sister, Yvonne, and stayed for most of August at Lynton College while she learned English. According to contemporary advertisements, the college was run by Mrs and Miss Wilson; it occupied a row of redbrick houses on Downs Park, a few minutes’ walk from the front, and backed onto tennis courts, where Duchamp spent much of his time. On 8 August he wrote to a friend, Raymond Dumouchel: ‘The traveller is enchanted. Superb weather. As much tennis as possible. A few Frenchmen for me to avoid learning English, a sister who is enjoying herself a lot.’ We know too that the siblings spent four days sightseeing in London, but whether they went to see Canterbury Cathedral, or struck out along the shore towards the ruined church at Reculver, there are no clues.

But what remains materially from those few weeks, apart from Duchamp’s brief correspondence, is sufficiently tantalising for the town to have marked the centenary of his visit with a three-week-long festival, several exhibitions and a symposium. During or soon after his holiday at Herne Bay, Duchamp made four drawings and a couple of notes that all relate to The Large Glass. The drawings are prototypes of enigmatic – animal, mechanical or anthropomorphic – elements in the achieved work: the ‘pendu femelle’ (an apparently female form that hangs at the top left) and the ‘sex cylinder’ or ‘wasp’ that attends it on the right. There is a colony of rare digger wasps at Reculver, which has excited some Duchampians, but the more obvious link to Herne Bay is in the notes. Duchamp tore out and kept a small photograph of the illuminated pier and wrote, apparently describing a potential backdrop for The Large Glass: ‘An electric fête recalling the decorative lighting of Magic city or Luna Park, or the Pier Pavilion at Herne Bay.’

It’s scant evidence. But the organisers of Duchamp in Herne Bay 1913-2013 have done their playful best with it. On 3 August a blue plaque was mounted at 14 Downs Park; and an exhibition at Herne Bay Museum and Gallery introduces the artist and tells what there is to tell of his unlikely stay. It is partly a matter of inflating the tiniest circumstantial clues to the status of the art-historical, and the festival perhaps wisely departs from the detail to concoct various cod-Surrealist, mock-Dada entertainments. A vast replica of Duchamp’s Fountain (the readymade urinal first shown in Paris in 1917) has been trundled through the streets, colourful ‘art bikes’ are parked about town in homage to his Bicycle Wheel, and local schoolchildren have been invited to deface reproductions of famous artworks, as per his defacement of the Mona Lisa, L.H.O.O.Q.

Compensatory silliness aside, there remains something compelling about the very lightness with which Duchamp touched the Kent coast. Early in the month Duchamp scholars convened to discuss what might be made of the story’s fragments; speakers described the entertainments Marcel and Yvonne may have attended, and noted the prevalent effects of spectacular seaside technologies on modernism in general. Perhaps unsurprisingly – given its location between London and the Continent, as well as its enlivening effects on convalescent artists – the coast of Kent is dotted with these historical connections to 20th-century experimentalists. T.S. Eliot recovering at Margate is the best known. (As at least one local wag has spotted, there is no tribute to Eliot attached to the seafront shelter where he composed The Waste Land, but it is close by the anagrammatic TOILETS.) Duchamp returned to the county in 1933, to play chess at Folkestone, and Beckett was married there in 1961.

The richest, because most ambiguous, treatment of the 1913 anecdote – and of the idea of foot-stepping modernism along this coast – is to be seen in Jeremy Millar’s film Zugzwang (almost complete), which was shown at the end of the Duchamp symposium. The film is mostly made up of footage of Herne Bay at the height of summer: a town barely hanging on to its role as resort, in the face of inexorable dilapidation and the loss of its most impressive attraction (the pier blew down in a storm in 1978, leaving its pavilion orphaned). Millar’s French narrator arrives hoping to retrace the journey of a scholar who in turn had been on the trail of Duchamp: the place becomes a constellation of barely credible clues.

The success of Millar’s film lies in the way he marshals the residue of Duchamp’s stay to tell a mock-academic tale that’s at once entirely fanciful and quite plausible. The narrator and his precursor – and by extension Duchamp himself – have been seduced by the architecture, topography and seafront amusements to the point that everything is a potential ingredient in The Large Glass. Bicycle wheels, a clock tower, the pallid arms of wind turbines out at sea: all seem to rhyme with Duchamp’s declaration of ‘a need for rotating circles’. Air vents above a modern pavilion recall a note by the artist concerning ‘three air current pistons’ in the projected work; the nested red buckets of a builder’s chute on Downs Park point to the conical ‘sieves’ in the bottom half of The Large Glass. And in a connection so frail one longs for it to be true, Millar points his camera at the former Lynton College and remarks on its sash windows, which he suspects Duchamp had never seen until he came to England. Perhaps he’s right. Duchamp’s note about the lights at Herne Bay contains, for the first time, the following instruction: ‘The picture will be executed on two large sheets of glass about 1m 30 x 1,40 / one above the other (demountable).’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.