Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life, curated by the American art historian Anne Wagner and her British husband T.J. Clark, is the most radical and exciting re-evaluation of a British artist I have ever encountered, and a thrilling display of how paint conveys ideas, time, place, building a self-contained world at once absorbing and convincing in its relation to lived experience. So, more or less (I have tinkered with it only a bit), began Jackie Wullschlager’s review of the Lowry exhibition (until 20 October) in the Financial Times. I was planning to begin with a similar bang myself, but as she went off first I just add my full endorsement. For me, and for many others, this show has been a revelation: the nature and huge importance of what Lowry achieved made apparent not just by the rare opportunity to see, in London, so much of his work at once, but by the brilliant interpretative essays by the two curators in the book that accompanies the exhibition (Tate, £19.99). I had not rethought my attitudes to Lowry since they were formed, casually enough, in my twenties, when he was so popular that he obviously wasn’t worth much. Like most people living in the South of England, I knew him entirely through those ubiquitous colour reproductions, and had no idea of him as a painter, of how he put paint onto canvas. He seemed to have ignored all that had happened to painting in the 20th century. His figures, someone told me once with warm approval, were ‘really sweet’, but it was those figures that seemed to me the very worst thing about him, a view reinforced ten years later by Brian and Michael in their song about Lowry’s ‘matchstalk men and matchstalk cats and dogs’. Those figures now seem to me to express an enormous thoughtfulness about the conditions and effects of life in industrial towns; and Brian and Michael, though I still can’t bear that matchstalk men stuff, were certainly more thoughtful than me.

If you had asked me to name a single British painter who had taken on the project of painting the landscape of the Industrial Revolution, the most life-changing event in the history of modern Britain, I would have no doubt replied that the answer was obvious: Lowry. It was the question that wasn’t obvious to me, until Clark and Wagner asked it. But I’m not sure that I would have thought the question important, even if it had occurred to me. Surely it mattered more to tune in (this was the 1960s) to the great movements of modernism than to attempt to show how the Industrial Revolution had shaped the environment of the North of England (which I had barely visited then). I had friends from Lancashire who were clearly scornful of my blinkered metropolitanism, but I was just as scornful of their parochialism. Lowry was, after all, a local painter – as though the same weren’t true of countless artists in the capitals of Europe. When I took on these attitudes I was writing a book full of admiration for John Clare as a local poet, and I was learning to admire Constable as, principally, a local painter. But to be modern was to be metropolitan; and to be a ‘local’ anything in the 1960s, even for musicians in Liverpool, was to have missed the bus to London. So for decades Lowry seemed to me no more than Coronation Street on legs, and not very well-drawn legs either. It took me decades to realise that even in the 20th century a local painter was something to be – and that he was very good at legs (see The Procession of 1927).

As his neglect until now by Tate Britain itself testifies, I wasn’t the only one to think this way; Lowry might have been popular among those who didn’t know much about art but knew what they liked, but I preferred the consensus of the sophisticated. Now that Lowry is suddenly a topic of conversation again, after decades of silence, it is apparent that these attitudes are still widely shared. This is the context in which Clark and Wagner are asking us, daring us if you like, to reconsider, and to rediscover Lowry as a local artist to be sure, but at the same time as a world-historical one. His art, Clark writes,

is modest, constricted, monotonous, awkward, ‘obvious’; and world-historical just because of these qualities. Because they are the qualities of the social order – the immense social fact – that Lowry chose to confront; and because he saw that the qualities could, if he tried hard enough, be made pictorial … could put him back in touch with ambitions and procedures (kinds of modesty and awkwardness) that had stood at the heart of the modern tradition only a generation before – in the effort, pursued above all in France through the later 19th century, at a ‘painting of modern life’.

Lowry as the successor to Seurat, Degas, Pissarro? It would have seemed absurd in London in the late 1920s and early 1930s, but not in Paris, where Lowry was regularly exhibiting and where a series of favourable notices, he said, ‘made me feel there was definitely something in what I was doing’.

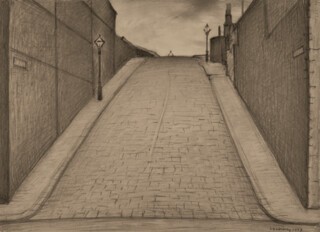

There are various ways of being a ‘local artist’, and Lowry tried out several. In 1930 he was invited by the Manchester University Settlement to mount an exhibition of his work, including drawings of Ancoats, the inner-city neighbourhood which had become a recipient of the settlement’s charitable work. The drawings are especially intriguing in that he seems to have used the opportunity to represent Ancoats by depicting actual places with a topographical accuracy which, on the evidence of this show at least, he had not attempted for several years and would attempt again only very rarely. The drawing from this series that seems to be attracting the most attention at Tate Britain is Junction Street, Stony Brow, Ancoats (1929, below). It is extraordinarily arresting, in part precisely because of its singularity: this place is like nowhere else he creates. A cobbled road enclosed between high walls leads up from the bottom corners of the picture and disappears over what is presumably the ‘stony brow’. The top of a street lamp is poking above the brow, but that is all. The converging diagonals of road, cobbles, pavements, kerbs, walls all promise to lead somewhere, but apparently lead nowhere. They abandon us at the top, with nothing to look forward to. A ‘strange tour de force’, one critic wrote. ‘Mysterious place’, the man standing next to me said. ‘Is this a place at all?’ Wagner asks.

This surely cannot be a place, for pictures are not made of such places, except those that get called ‘imaginary landscape’ or are claimed to have been visited in dreams. To us it is nowhere; but we are not the intended spectators. These pictures of Ancoats drew deeply, Wagner points out, on Lowry’s fund of local knowledge, and they appealed to, asked to be validated by, the local knowledge of a local audience, people who lived or worked there, or for one reason or another knew the area well, even though few of them might hear about the exhibition, let alone visit it. To such an audience, Junction Street would have been one of the least strange, most familiar places they knew. It linked two principal streets in the area, Store Street and Ducie Street, and bridged the Ashton Canal at its junction with the Rochdale Canal. Lowry’s drawing is very like the photographs of Junction Street, now Jutland Street, on the internet.

What was the point of showing a local audience a place already thoroughly familiar to them? Partly, no doubt, to offer them the simple pleasures of registering its familiarity (‘I know where that is’) and the intriguing exactness of the representation (‘and it looks just like that.’) At the end of Junction Street where Lowry made his drawing, the wall on the right was made of roughly dressed stone, the one on the left of brick; his intended audience might have noticed how careful he had been to preserve those different textures. Nearly at the brow, on the right, he had even registered the break in the pavement just before the bridge that would later become the entrance to a breaker’s yard. But Lowry was offering strangeness too, though of a different kind from what we experience at Tate Britain, by showing them that this familiar, undecorated, ruthlessly functional slice of the inner city, their slice, where they belonged and where we would have no reason to go, was worth representing, was a subject for art. For us in the Tate, Junction Street is a landscape of sorts, but is it really a place? To the real or imagined Ancoats audience, the place is real enough, but the drawing proposes that Junction Street is not just a place; it can be a landscape too. One way or another, all the drawings I have seen from the Ancoats series seem to invite the same understanding.

Lowry’s status as a ‘local’ painter is not usually staked on this kind of topographical exactitude, however, and if he came to be thought of in Manchester as a pre-eminently local artist, a painter of Manchester for Manchester, this was on the basis of his vast output of imaginary landscapes. Those made in the late 1920s through to the war years, in particular, are made from a few repeated motifs, different each time they appear but similar enough to persuade us that we have seen them before, that they are known to us, part of the familiar furniture of his city. There is a grimy, pink-washed, usually single-storey building with a slate roof and tall windows rounded at the top, which appears and reappears as a school, a mission, a factory and other buildings of uncertain character. There are terraces of houses, usually of two storeys, usually of red brick. There is a gateway pierced through a wall or a run of railings, often with a lantern suspended above it like the one outside 10 Downing Street, though plainer. There are warehouses and mills of soot-smudged yellow ochre, surmounted by squat square towers or cupolas. In the middle and far distance, there are chimneys everywhere, and the smoke-blackened spires and towers of churches, though as Lowry grows older the churches are crowded out by more and more chimneys.

The repetitiveness in these pictures has been seen as evidence of Lowry’s limitations; the narrowness of his interests and imagination, what he himself described as his ‘obsession’ with the industrial landscape of Pendlebury. For Wagner, however, repetitiveness was vital to Lowry’s project as a local painter. Sooner or later these repetitions would come to seem merely repetitive, ‘run of the mill’ as she puts it, and something else would have to be tried; but until that time ‘they were a way of matching his pictures’ rhythm to the life of the street. Repetition … offered a means to expand the components of a single city street – chimneys and smokestacks, doors and windows, stairways and fences, men and women – into a world that seems cohesive, complete.’ The repetition of motifs that are similar but never the same enables Lowry to produce images with a reach and range far beyond what he could ever have achieved by a regime of deliberate topographical exactitude. In the Ancoats drawings, you either recognise the place or you don’t; they are either of your place or they aren’t. The places in these paintings are never any particular place, but are recognisably similar to many places. They can be felt to be ‘local’ by many people living in industrial Lancashire; they appeal to a common experience, to a common life in many places across a wide region.

All those repeated motifs are arranged front-on to the viewer, on the far side of a street running across the foreground like a stage, and made up of a series of horizontals – tramlines, kerbs, paving stones – with vertical accents provided by lamp-posts, telegraph poles, stench pipes, bollards, iron railings and bits of wooden fence that often function as repoussoirs, to push us back and remind us that our place is in front of the picture, outside it. This place belongs to the people on stage, whether just loitering there, ‘standing about’, as Lowry described them in the title of one painting, or going about their lawful occasions, from left to right, from right to left, shopping, strolling in the park, hurrying to a football match, walking the dog, going to school, tramping to the mill in the half-light of a winter’s morning, tramping home in the twilight, tired footsteps all but audible in the gallery. ‘My grandmother wore clogs,’ one smartly dressed Friend of the Tate said to another, claiming kinship with an old woman peering into a hawker’s cart and at the same time acknowledging the distance between them.

Some of these street scenes are cramped, claustrophobic, a feeling often accentuated by an opening between buildings that leads through to an equally narrow, cramped street beyond. In some others however the stage is deeper than a street’s width, the confining buildings pushed back beyond a more or less crowded open space. In these pictures things are happening. In Something Wrong (1926), later retitled An Accident, a small tight crowd has gathered round what we presume to be a person prostrate on the ground; from all around people are hurrying to find out what’s up. In The Arrest (1927), a man standing outside his own front door, watched by a gathering crowd, is tapped on the shoulders by two plain-clothes policemen. In The Removal (1928, above), a family that may have overstretched itself by renting a house with a small front garden is being evicted for non-payment – an event Lowry, a rent collector by profession, must have witnessed often, perhaps often initiated. Their furniture is outside, divided into two lots, one in the garden presumably for them to keep, the other out in the street, distrained by the bailiffs who are arguing over it with members of the evicted family.

On many of Lowry’s more open stages small crowds gather, to witness someone else’s bad luck, or to listen to political speeches or religious harangues, or to watch a procession pass and to be seen in their weekend clothes. His men and women register, not in their usually unreadable expressions but by their movements and postures, a wider range of feelings than we usually meet in figures in landscapes: enthusiasm, reluctance, eagerness, weariness, the pleasure they take in the company of others and so on. Since visiting the exhibition I have been remembering in particular two youngish men embracing each other with huge delight at a funfair. When the picture was first shown, in 1946, they must have been understood as two demobbed soldiers, friends meeting for the first time in years, each overjoyed to discover that the other is safe and well. But many of Lowry’s figures seem to feel nothing, as if seeming to feel nothing is the best way to survive these streets. It is Lowry’s way of coping with them too, Clark argues. The paintings are as consistently affectless as Kafka’s novels, inventing narratives that in other hands would invite our sympathy, but in Lowry’s, like shit, just happen.

Clark and Wagner approach these incidents in the street by reminding us that in the crowded towns of industrial Britain life was lived much more in public than it was in the new suburbs; space was in short supply, so anyone’s business became everyone’s business. Lowry’s project, they argue, was possible only because ‘modern life’ was still lived outdoors in the parts of Manchester he knew best. In the suburbs modern life had moved indoors, and had become invisible to the artist as flâneur, or rent collector. In the whole exhibition, the superb image of the new National Health Service, Ancoats Hospital, Outpatients Hall (1952), is the only painting of an interior – a public institution where life is lived even more in public than it is on the street. In the paintings of incidents in the street, curious spectators poke their heads out of their front doors, apparently accepting, even enjoying, publicity as a fact of life and a source of entertainment. But perhaps the most striking figures are those that hover on the edge of these narratives, unsure what to feel. There are several in The Removal, full of curiosity about what is going on, but stood at a tactful remove, evidently reluctant to get too close. Their posture shows at once their wish to stay and watch, and their sense that they should really be moving on. They register the impossibility of privacy at the same time as they sense the need for it. If they could afford to, they would be the first to move away; perhaps to somewhere like the big bourgeois detached house in Eccles Old Road, thickly painted by Lowry in 1913. Dark red brick and slate, with the portico of a gentleman’s residence, solid and safe behind its shut wrought-iron gates, its low wall and railings, its palisade of shrubs – it’s the kind of house Lowry’s mother longed to live in, where what happens inside stays inside, invisible, inviolable, at least while the money holds out.

It was around 1940 that Lowry’s repetitions seem to have struck him as merely repetitive. From about then his eye floats upwards, to somewhere a good few feet above the ground; roads are pushed through the centre foreground to the middle distance and sometimes beyond, so that now the distance from front to back is measured not only by the horizontal rows of buildings, one behind the other, but by the lines of roads receding, converging, apparently going somewhere. The landscapes from this period, especially those gathered in the last, monumental room of the exhibition, are no longer particularly local, though one claims to be of Ashton. They are undisguisedly imaginary landscapes, most of them with deliberately generic titles: Industrial Landscape (four of these), Industrial City, Industrial Town, Industrial Scene, Industrial Panorama. Some of these pictures are huge, by Lowry’s previous standards, five feet wide and more, and they show Lowry, in his sixties, developing a quite new notion of how it might be possible to paint ‘the industrial scene’.

These pictures look very similar but they are very different. A few of them are paintings the curators read as ‘reparative’ of a land and an economy devastated by the war, and some of them, The Football Match (1949), The Pond (1950), the Industrial Landscape of 1955, seem to respond well to being approached in those terms: a community apparently ‘getting back to normal’, a huge prospect, made available by the high viewpoint, of a once more flourishing millscape, mapped onto a reassuringly legible geography. Others, like Industrial Panorama, seem to show a human-sized industrial village, its busy but peaceful chimneys filling the sky with smoke. Others again – the Industrial Landscape of 1953, the view of Ashton, the River Scene (1950) – display an endless, formless prospect of an industrial nation in irreversible decline, with mills and houses adrift in a polluted sea of lost connections. In these images most of the chimneys are smokeless, as if most of the mills have closed, and the ground, though deeply scarred, seems almost clean, compared with the soot-encrusted satanic millscape of Wigan, painted in 1925, where even the sky looks in need of a good scrape. ‘These paintings,’ John Berger wrote in 1966, ‘are about what has been happening to the British economy since 1918, and their logic implies the collapse still to come.’ Here are ‘the obsolete industrial plants; the inadequacy of unchanged transport systems and overstrained power supplies … the shift of power from industrial capital to international finance capital’ and so on. Here is the self-consciously world-historical Lowry, showing us Britain mired in its past, and perhaps the future of China. But here and there is the old local Lowry, whose people cannot see beyond the foreground terraces to the dystopian prospect, and so seem to manage, to cope, even to enjoy themselves, on their own tight patch. People stop to chat or just to stand about; kids play; dogs and babies get taken for walks; women wear bright vermilion, the happy colour of the summer of 2013, and apparently of 1950 too. It’s hard to say this without sounding as folksy as Brian and Michael, and perhaps that’s exactly what it is, but right now what I most admire and enjoy about Lowry is the interest he shows, without any apparent agenda, in what people do. I have no idea why that should be so moving.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.