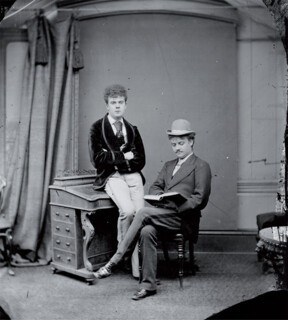

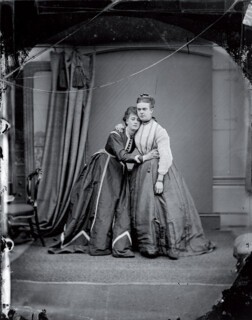

Beneath their capacious skirts, Fanny and Stella were Frederick Park and Ernest Boulton, two young cross-dressers who were put on trial in Westminster Hall in 1871. Cross-dressing was not a criminal offence, so the men were charged instead with outraging public decency. On the slightest of pretexts, the prosecution also threw in ‘the abominable crime of buggery’, along with conspiracy to incite others to do the same.

This was serious stuff. Only nine years before, buggery in England had carried the death penalty, and could still mean penal servitude for life. Anal intercourse with a woman was also illegal. Rapists, murderers and sodomites condemned to hard labour spent long hours picking oakum, walking the treadmill or operating a crank. Park’s brother Harry, a male prostitute like himself, was sentenced to a year’s penal servitude in the House of Correction in Coldbath Fields, which with its appalling food, lack of sanitation and back-breaking toil was generally considered close enough to a death sentence.

Both Park and Boulton were of impeccable middle-class pedigree. Park was brought up in Wimpole Street, the son of a judge, while Boulton, a stockbroker’s son, worked in a bank. Yet as well as being cross-dressers they were also part-time male prostitutes. Male prostitutes in female guise meant competition for female streetwalkers, not least since a good many drink-befuddled customers actually mistook them for women, an illusion that the whore himself could foster by a deft substitution of orifices. Prostitutes rarely undressed, permitting penetration through strategic slits in their knickers. Dragged-up male sex workers could thus be set on by outraged female streetwalkers as well as by common or garden homophobes. By contrast, women on the game who offered what was known as a ‘thrupenny upright’, along with more costly horizontal favours, felt little threat from male prostitutes who looked like men, since it was unlikely that punters attracted to them would fancy women as well. Relations between women sex workers and the ‘gaggles of Mary-Anns waggling their scrawny arses up and down the street’, as Neil McKenna depicts them in his tiresomely spiced-up style, could be remarkably cordial. According to one Victorian writer, a ‘notorious and shameless poof’ married a street woman and fathered two sons with her, both of whom followed in their father’s professional footsteps. A male prostitute known as Fair Eliza kept a fancy woman in Westminster who, McKenna writes, did ‘not scruple to live upon the fruits of his monstrous avocation’. Female sex workers might help procure young men for their more sexually versatile clients.

Hundreds, perhaps thousands of so-called he-she ladies were arrested each year and charged with what the newspapers called ‘abominable offences’, ‘unnatural crimes’, ‘uncleanness’ or ‘unspeakable conduct’. Some of them got off by offering police officers sexual or financial favours. ‘I have been in the hands of the police,’ one young adventurer wrote home to his ‘Pa’, ‘or rather the other way round, the police have been in my hands so many times lately that my lily white hands have been trembling, and I am utterly fucked out.’ (If the word ‘Pa’ is to be taken literally, the youth must have had an astonishingly broad-minded father. Boulton’s mother was almost as permissive, fondly pasting photos of her son in drag into an album.)

McKenna says it was common practice for policemen to request sex from male prostitutes and afterwards demand money from them. Even if they paid up, they might still be arrested on the charge of indecently assaulting a police officer. Cops hung around public lavatories to spy on potential transgressors, a practice one magistrate deplored. ‘The system,’ he said, is ‘bad for the constables themselves, as after a time their minds become, as it were, diseased by being bent on the same point.’ Newspapers speculated on the existence of a well-organised conspiracy of sodomites intent on sapping the morale of the nation. Before too long, men in drag might be driving around in open carriages. It was hard to say how common buggery was; but masturbation was certainly widespread, and since it drained a man’s virility, it represented the thin edge of the androgynous wedge. ‘Androgynism,’ one medical journal declared, ‘may be taken to mean the intrusion of either sex, voluntarily or not, into the province of the other; to wit, when a woman dissects a dead body, or a man measures a young woman for a pair of stays.’ It was a question of gender roles, not anatomical ambiguity.

Despite the perils of gay encounters, London was packed with male brothels. On one estimate, two thousand out of a total of five thousand knocking shops catered specially for men in search of boys. There were even bordellos specialising in particular types of youth: butcher boys, errand boys, sailor boys, drummer boys and so on. (One wonders how many bent drummer boys the sex industry could muster.) An enterprising young man could make as much as £10 for sex with a client. Private drag balls were a regular feature of London life. In 1854, a court was informed that the sixty-year-old man in the dock had been arrested at such a gathering for being dressed in the pastoral garb of a shepherdess of the golden age. In Manchester, a detective sergeant knocked on the door of a Temperance Hall, uttered the word ‘Sister’ in a mincing voice and had the door opened to him by a man dressed as a nun. Inside the hall, the officer later testified, a group of men were performing ‘a sort of dance to very quick time, which my experience has taught me is called the “Can-Can”’.

It could be dangerous for men openly to buy women’s clothing, but the burgeoning mail order industry could supply male cross-dressers with every kind of corset, stay, busk or truss, along with hair removers, breast enlargers and the monstrous hairpieces known as chignons and frisettes. The procuress Madame Rachel was said to wear such a mighty chignon that her legs were bowed by the strain. A weak solution of arsenic was thought effective for removing facial hair. There were hairdressing establishments in the West End from which bearded young men could emerge after an hour or so shaved, rouged and chignoned. Fanny and Stella may have had recourse to the Registered Bust Improver, which used air inflation. Some French male prostitutes were rumoured to wear false bosoms made from boiled sheeps’ lights; one complained that a cat had eaten his breast. There was also a brisk trade in chloroform, a gas which might have been specially invented for Mary-Anns. Its vapours were thought to loosen and widen the back passage, as well as to induce erotic sensations. Injected directly into the rectum, it was considered therapeutic for a variety of anal disorders. In a miracle of multitasking, it could also be used to knock out obstreperous punters, who might then be dumped comatose in alleyways.

Disease, however, was a perpetual problem. Park developed a sore on his anus that he assumed was the result of being too vigorously sodomised, but turned out to be syphilis. Rectal syphilis and gonorrhoea were common enough in female prostitutes, but reports of them in men were rare. Fearful of being shopped to the police by a moralistic medic, Park, well practised in impersonation, visited a doctor disguised as a down-at-heel working man. Boulton suffered for years from an anal fistula that was finally treated by surgery.

As a cross-dresser, Boulton was hailed as a beauty whereas Park was not. As McKenna remarks in one of the few aesthetically pleasing sentences in the book, Boulton ‘was tall and slender, with a narrow waist and a magnificent bosom, her finely shaped head topped by raven hair fashionably dressed in the Grecian style with coils of plaited hair held in place by a crosshatch of black velvet’. Park was stouter, more jowly and more matronly. A dust-jacket photograph of him in drag doesn’t make it easy to see how he could have been mistaken for a woman by any sober, keen-sighted client in a moderately well-lit street. There is also a photo of Boulton which suggests that despite McKenna’s effusions he was no Angelina Jolie.

Even so, the sexual ambiguity of the pair was not simply a matter of painting their faces. There was no clear-cut contrast between appearance and reality. Rather, the duplicitous appearance lay in the reality itself. One of the medics who examined the men after their arrest was struck by the smoothness and translucency of their skin, their slender waists and shapely buttocks; nor did he find their anuses grotesquely dilated: the pair seemed to him to be graced with young women’s bottoms, with small rectums and tight sphincters. The magistrate who dealt with them knew they were men but referred to them in court as women. They were sometimes taken for men when they dragged up as women, but when they dressed as men they could be mistaken for young women in male drag. It was as though what they really were was itself a form of disguise.

The two men were arrested outside the Strand theatre in April 1870, where they were observed to simper, giggle, flirt, mince, wink and smirk, lasciviously ogling the male occupants of the stalls and engaging in bouts of ‘chirruping’, a loud sucking noise made with fluttering lips which some members of the audience complained almost drowned out the performance. A group of police officers who had had them under surveillance for some time seized their opportunity and pounced. Boulton gave his name as Cecil Graham, which Wilde was to use twenty years later as the name of a character in Lady Windermere’s Fan. He knew of Fanny and Stella, having read an account of their exploits in a pornographic work from which McKenna quotes with a certain relish. The arrest was a worrying moment for John Fiske, the American consul in Edinburgh, whose love letters to Boulton were already in the hands of the police and who was no doubt looking into diplomatic immunity. It was also a troubling time for Lord Arthur Pelham-Clinton, son of the Duke of Newcastle, who had lived with Boulton for some time, and was also arrested. Lord Arthur’s escape route from a long term of imprisonment was not diplomatic immunity but death: in a dry run for Lord Lucan, he broadcast news of his own demise and even arranged a funeral for himself.

After their arrest, the two ‘sisters’ were examined by a police doctor. He found their anuses to be dilated and their genitals elongated, in Boulton’s case ‘enormously’ so. This, the physician observed, was a result of ‘traction’. He also believed, following a French authority on the subject, that the penises of active homosexuals were ‘pointed and moulded to the funnel shape of the passive anus’ and twisted as a result of the ‘corkscrew motion’ of sodomy. The two men were examined again before their trial by no fewer than six doctors, all of whom took turns to stick their fingers up the pair’s backsides, and five of whom testified that they could find no signs of buggery. The dissenting medic found evidence of the crime in the fact that the puckering of the skin around Park’s anus had been partly eroded, perhaps by the pumping action of a penis.

The show trial of the he-she ladies proved an embarrassing anti-climax. Park and Boulton were symbolic representatives of what was feared to be a more pervasive moral degeneracy, and so short of rooting out the whole of English sodomy at a stroke, there was no way the prosecution could have succeeded. The two defendants could not be charged with wearing drag or with any actual act of sodomy, so they were accused instead of conspiring to ‘openly and publicly pretend and hold themselves out and appear to be women and thereby to inveigle, induce and incite divers of the male subjects of Her Majesty improperly, lewdly and indecently to fondle and toy with them as women and thereby openly and scandalously to outrage public decency and to offend against public morals’ as well as conspiring ‘to solicit, induce, procure and endeavour to persuade persons unknown to commit buggery’. The court, however, was longer on words than on evidence. There were also clear indications of spying, bribery, collusion, police corruption and political interference. The treasury solicitor, it emerged, had taken personal charge of the prosecution from the outset, while the home secretary had expressed a strong personal interest. So there was indeed a conspiracy, but not one of sodomites. The jury was out for a mere 53 minutes before returning a verdict of not guilty. Park died of syphilis ten years later at the age of 34, while Boulton died, probably of the same disease, aged 54.

McKenna has made assiduous use of the trial transcripts, as well as of letters and depositions. He is, however, the kind of author who in the absence of hard evidence resorts to the well-tried scholarly technique known as making it up. ‘Inspector Thompson,’ he writes at one point, ‘permitted himself a rare smile of satisfaction.’ The truth is that McKenna hasn’t a clue whether he did or not, since the inspector was alone on a train at the time, and there is no source supplied for the comment. A whole chapter about Park’s childhood, couched in sickly-sweet prose, seems largely invented. The more McKenna’s style strays into Mills and Boon fantasy, the surer one can be that he has nothing concrete to go on. Fanny and Stella, described on the dust jacket as ‘dazzlingly written’, is full of naff phrases and clichés. Bouquets are the order of the day, advice is sage, disasters are unmitigated, rooms are too small to swing a cat in and events go swimmingly or arrive like a bolt from the blue. The book is full of arch, feeble, nudge-wink humour: the only tolerably good joke – describing an ambitious politician as a ‘rising Member’ – may be unintentional.

Fanny and Stella’s outfits, McKenna informs us, were rather tawdry – glittering enough on the surface but cheap and threadbare beneath. Like his young men, McKenna builds an elaborate superstructure on a slim base. There are some alarming outbursts of fine writing, as in this account of Fanny and Stella’s sobriety of mien in court: ‘There was no more giggling or flirting or ogling or chirruping. There were no more hissing sibilants; no more contemptuous snorts; no more withering looks; no more tossings of actual or imaginary curls; no more flutterings of eyelashes; no more swishings of metaphorical bombazines.’ McKenna’s style paints as thickly as his subjects, as full of flamboyant hyperbole and extravagant flourishes as the camp young fellows it portrays. When the attorney-general enters the courtroom to prosecute the accused men, ‘it had been many a long year,’ McKenna writes, ‘since [he] had stripped down to his long drawers and stepped into the ring for a bare-knuckle, bloody fight, ably seconded by the solicitor-general brandishing a sponge soaked in vinegar.’ It’s surprising that he doesn’t tell us that the attorney-general came clothed in the shorts of moral bigotry and protected by the gum shield of arrogance.

The case of Fanny and Stella was a rare victory for the hounded and harassed, and an agreeable defeat for a benighted Establishment. In this sense, it represents the reverse of the Wilde affair, on which McKenna has written previously. Park and Boulton seem to have behaved astutely in court, as Wilde most certainly did not. It is a pity, then, that such a powerfully symbolic event should be treated so self-indulgently. One can appreciate the unimportance of being earnest while still hankering for a touch more seriousness.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.