How will we feel, seeing photographs hung for the first time in a temple dedicated to painting? That is the experiment the National Gallery has undertaken with Seduced by Art: Photography Past and Present (until 20 January). A cautious experiment, in that Hope Kingsley, the curator, has selected only photographs consciously created in relation to the painting tradition – pictures she is able to group under the traditional genres of portrait, landscape, still life and so on.

Partly as a result, her vivid, quirky survey has a peculiar historical shape. As an expert on mid-19th-century ‘art photography’, Kingsley presents some practitioners we have become used to taking seriously – Gustave Le Gray, Roger Fenton, Julia Margaret Cameron – and others we still cannot, notably Oscar Rejlander, whose composite photo-allegory The Two Ways of Life (1857), replete with draped, earnest males, nude, lubricious females and deferences to Raphael, amused Queen Victoria. Kingsley is not however concerned with later ‘pictorialist’ photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz or F. Holland Day, who worked at the 20th century’s turn: still less with the 20th-century photographic mainstream, with its search for values specific to the medium. Instead, she leaps forward to the ‘photo-work’ that started in the 1970s – a return to historically self-conscious picture-making epitomised by artists such as Jeff Wall.

The point of the experiment remains to bring out whatever those medium-specific values might be. The inclusion of a few canvases sets up interesting tensions. George Frederic Watts may have been Cameron’s mentor in developing a modern heroic portraiture, yet when their respective visions of Tennyson’s daughter-in-law May Prinsep are set side by side, I find that his tremulous, scrawny brushwork sets me on edge, whereas the lush, misty sepia of her albumen print draws me in. Contrast what happens with the latter-day heroic portraiture of the feminist 1980s. Maud Sulter trained a camera on her own head and shoulders, isolated in darkness, and printed up a large, gilt-framed cibachrome which Kingsley hangs close to a 1649 portrait of a Dutch female scholar. Simply through her choice of image, Sulter seems to have said: this skin of mine has a sensual allure that is all of a piece with my self-command; I know what I’m about, just as Jan Lievens’s sitter did. But Sulter’s rhetoric of sensuality butts against the slick, hermetic coating of the dyed polyester sheet. The affectlessness jangles, an effect of aggressive, alienating, Vogue-like glamour that the artist presumably allowed for. (Much the same complexities arise when another 1980s photo-artist, Helen Chadwick, juxtaposes her own nude body against rotted vegetables and a skull in the photo-allegory Ruin.)

Craigie Horsfield approached the matter at hand when in 1991 he complained that ‘the surface of the photograph is redundant.’ Everyday, functional photos are items to look through, rather than at. The physical mismatch with what they purport to represent can be disturbing. Kingsley notes that still life has now become ‘the most widely seen photographic subject’, and I’m reminded of how I have to reel in my distaste, when scanning a pizza menu, at the actual reds, yellows, greens and browns of the still lives it displays: the higher the res, the sharper the nausea. Horsfield’s own pictures reaffirm the customary wisdom of art photography, that colour and definition are qualities to hold at bay. In outsize prints of a woman’s bent and naked back and the head of a handsome Spaniard – the latter on watercolour paper – his matt pigments gather in soft black snowdrifts, blankets beneath which the human subjects lie dreaming.

Reverie is the destination, much as with Cameron. Alongside the younger Richard Learoyd, Horsfield believes in slowing down attention, their art photography posited as some form of redemption from fast-food values. Learoyd uses long sittings with a camera obscura to create one-off large-scale prints of solitary individuals, pensive and often vulnerably naked, under muted lighting. They ache so with the attempt to attach to another’s quiddity as to become acutely mesmeric. You might argue – I think Learoyd would – that they close in on the essence of the medium in their yearning to capture evidence of what’s unique and contingent. And yet surely that’s also the drive behind the finest paintings by Lucian Freud.

More frequently, the camera’s capacity to collect evidence disrupts whatever is painting-like about the image. Photos by Tina Barney, a portraitist of contemporary aristocracy, share space with Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews. For all the continuities of content, no detail of the latter resonates as does a loose wire recorded dangling beneath a sideboard, in a grandee’s dining room – a gift to Barney, opening up thoughts about the frailty of her well-heeled subjects in a manner unavailable to wilful brushwork.

Strikingly, the opening room’s main exhibit, the work that more than any other relaunched photographic academicism in the late 20th century, opposed itself at once to surface interest and to evidential status. Jeff Wall in his Destroyed Room of 1978 reinterpreted the busily violent composition of Delacroix’s Death of Sardanapalus as a mutilated assemblage of furniture inside a constructed proscenium, and blew up the resulting image onto a billboard-sized lightbox. It glares at you, aggressively and affectlessly: but if you look in, all you encounter is reflection on art history. An arid, joyless ingenuity, so it seems to me: but then I feel much the same about the Delacroix itself. And yet how perfectly Wall’s cake-and-eat-it formula for picture-making – to ‘participate with a critical effect in the most up-to-date spectacularity’ – spoke to those who, mourning the old avant-garde, still wanted somehow to join up the campus and the street. How generative it has proved: as the works of Ori Gersht, Beate Gütschow, Sam Taylor-Wood and Tom Hunter here demonstrate.

Doubtless Luc Delahaye was also influenced by the new academicism when he withdrew from twenty years of war reportage to devise large-scale digitally modified compositions. But the difference in background is crucial. Kingsley has included Delahaye’s three-metre-wide figure-packed panorama of a 2004 Opec conference table and a vista, almost as large, of dry fields in Afghanistan, overhung by distant mountains and smoke clouds. Delahaye’s reply when asked about their kinship to pre-modernist paintings is that ‘the paths of the photographer, who took reality as a subject, and of the painter, who took reality as a model, are crossing somewhere.’ Drawn into that far valley, to some mid-air point between the stubble, the smoke and the unseen holes where people are dying, I would add that his fastidious representation seems to renew that word ‘reality’, saying as much as can’t be said about a major communal concern: and that this might be an agenda two media could embrace in common.

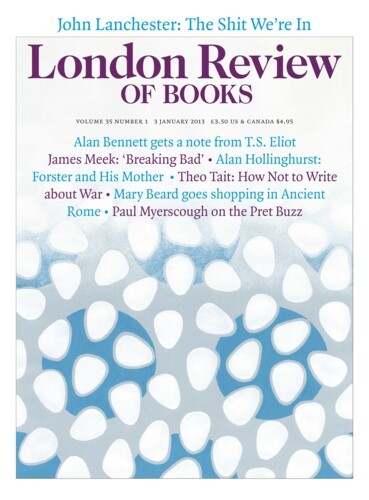

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.