Richard Hamilton, who died on 13 September at the age of 89, invented the idea of Pop art, along with his colleagues in the Independent Group, more than 50 years ago. In ‘Persuading Image’, a lecture he gave in 1959, Hamilton argued, well before it was a commonplace, that consumer society depends on the manufacturing of desire through design, forever updated by the forced obsolescence of style. ‘Is it me?’ he wrote, mimicking the adman mimicking the customer: ‘The appliance is “designed with you in mind”.’ His ‘tabular pictures’, a central contribution to Pop painting, work over this interpellation of people by images, indeed as images, and they do so in a meticulous manner that shimmers between the analytical and the fetishistic. Today our life as homo imago seems almost natural, each of us, as Hamilton forecast, a ‘specialist in the look of things’, designer and designed in one.

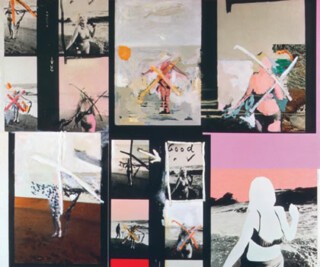

Hamilton explored the new relay between self and image directly in his own version of the ultimate Pop icon, Marilyn Monroe, made after his first visit to the United States in 1963, where he travelled with his friend Marcel Duchamp, and met Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Ed Ruscha and other young bucks of American Pop art. In My Marilyn (1965) Hamilton adapted, in painting, part of a contact sheet from a photo shoot by George Barris that included her own editorial indications as to which images to cut and what pose to permit – in short, how to look, to appear, to be. In the rough grid of the painting a cluster of four images appears twice, with slightly different markings and croppings, once at upper left and again, a little smaller, at centre bottom; each of the images also appears, enlarged, with further alterations by Hamilton, in the other rectangles of the painting. The most dramatic changes are wrought on the one image approved by Marilyn (marked ‘good’): here the colour is that of a deteriorated photograph (the sky and the sea are two bands of lurid pink and orange), and her body is whited out, as if in negative, as if she were already absent (as indeed she was in 1965). Although the Marilyn commemorated by Hamilton is still a star, she is less an erotic object than an anxious designer, the stringent artist of her own powerful iconicity, a merciless editor of her own public appearance. Perhaps Hamilton identified with this editorial rigour; certainly he agreed with her implication that being is imaging in the Pop age.

How different this relation to Monroe is – more pointed, in my view, more poignant – from the agitation acted out by de Kooning or the thrall suggested by Warhol. Hamilton elaborates not only on the expressive possibilities that Marilyn offered (apparently she would mark her contact sheets with whatever was at hand – lipstick, nail-file, scissors) but also on the psychological states that she evoked, which range, in his words, from the ‘narcissistic’ to the ‘self-destructive’. All at once Marilyn appears to desire, even to solicit, our gaze (that this gaze is captured is the sine qua non of celebrity), and to fear, even to refuse it (rightly so, perhaps, given that her masochistic marking seems to anticipate our invasive looking). In this regard we might compare My Marilyn with the other great Hamilton essay on the problematic glare of celebrity, Swingeing London 67 (1968), his lurid painting of Mick Jagger and Robert Fraser (an art dealer of the time) manacled together in a police van after a drug bust.

We tend to see Pop artists as utterly seduced by images of personages and products, complicit with the amnesia that consumerism needs to produce. Yet sometimes, against the odds, they were able to produce a mnemonic art out of these materials. Warhol once grouped his great silkscreens of the early 1960s – car crashes, tunafish poisonings and race riots – under the rubric ‘Death in America’, and they do illuminate the dark side of the Kennedy-Johnson years like no other representations. Gerhard Richter, with his sequence of paintings of the Baader-Meinhof Gang made in the late 1980s, also revived history painting for a troubled country, and like Warhol featured subjects wholly alien to the proper figures of official history. But Hamilton may have exceeded both his peers in this regard.

For example, when I think of ‘swinging London’ in the 1960s, I see his Swingeing London 67, and when I think of the state violence visited on the student movement in the US, I see his Kent State (1970), a palimpsest of a print of a fallen protester shot by a National Guardsman on the Ohio campus. In his installation Treatment Room (1983-84), a clinical room with a white gurney and a bleak blanket, Hamilton returns us to the nasty surgeries performed on the body politic by Thatcher. He also reflected on the comic-tragic Anglo-American adventure in Iraq in paintings from War Games (1991), where we see a TV image of toy tanks massing at the Kuwait border, to Shock and Awe (2008), a portrait of Tony Blair as a wannabe gunslinger in a firefight turned cataclysmic. His best work in this vein is the sequence of three paintings on the Troubles: The Citizen (1981-83), which shows an emaciated IRA prisoner who has gone ‘on the blanket’ and smeared his cell with shit; The Subject (1988-90), which depicts an old Orangeman on a Loyalist march in pompous regalia; and The State (1993), which presents a young paratrooper, camouflaged and armed, on anxious patrol.

What makes an image iconic? Somehow it stems from the present even as it evokes the past. Hamilton was a master at this spiking of the contemporary with the historical; he had an almost Warburgian ability to pick out the pose or the gesture that would both resonate across culture and reach back in artistic time. For all their contemporaneity, the wounded student in Kent State calls up the dead Christ of Mantegna (even as it anticipates the fallen terrorists of Richter), and the hunger striker in The Citizen calls up Dürer’s Man of Sorrows (even as it anticipates Agamben’s connection between homo sacer and sovereign power). This is what makes Hamilton so special: he presents an ‘ironism of affirmation’, as he once put it, a mix of reverence and cynicism, to popular culture and high art alike. By ‘modernity’, Baudelaire wrote in ‘The Painter of Modern Life’ (1863), ‘I mean the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art whose other half is the eternal and the immutable.’ In 1957 Hamilton defined Pop too as ephemeral, yet he agreed with Baudelaire that the artist must work ‘to distil the eternal from the transitory’. With Hamilton this great project of modern representation was brilliantly continued.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.