The latest wave of the Scandinavian crime invasion: Sarah Lund and her woolly jumpers. The Killing, the powerfully addictive Danish crime drama running on BBC4 on Saturday nights, has become the latest TV series to inspire a devoted, evangelical following, just as it did in Denmark when it was first broadcast in 2007 under the name Forbrydelsen (‘the crime’). The series tells the story of a 20-day investigation into the murder of a 19-year-old girl, Nanna Birk Larsen, in a gloomy November in Copenhagen, unfolding over 20 hour-long episodes. Central to its appeal is the heroine, Sarah Lund, a laconic, mournful-eyed detective played by the wonderful Sophie Gråbøl. Lund is famous for her obsessive, intuitive investigative style and her chunky knitwear. Her signature cream and navy Faroe Islands sweater, slashed by a sex offender in an early episode but later repaired, sold like hot cakes in Denmark (a snip at €280, it is available from the Faroese firm Gudrun and Gudrun).

It is a jumper of great depths, as Gråbøl, who chose it herself, explained in a recent interview. ‘It tells so many things to me about the character,’ she said. ‘It tells of a woman who has so much confidence in herself that she doesn’t have to use her sex to get what she wants.’ It also tells us that, unlike Helen Mirren in Prime Suspect, she doesn’t have to power-dress or demand that people call her the guv’nor. ‘She’s at peace with herself.’ Furthermore, it hints at Lund’s left-wing, guitar-playing hinterland, which is pleasingly at odds with her tough, uncompromising character. She behaves as a classic male detective would (‘like Clint Eastwood’), neglecting her son and her handsome but drippy Swedish boyfriend, Bengt, in order to wander around pitch-black cellars with a flashlight, solving crimes.

I keep reading that The Killing is a) realistic and b) free of all the usual clichés of police procedurals. This is rubbish. The series begins with a welter of clichés: a girl chased through a dark forest, amid chiaroscuro lighting, by a remorseless pursuer. The initial set-up – a body found in a car in a canal – doesn’t rise much above Waking the Dead. The plot is amazingly contrived, the array of convincing possible culprits mind-bending. There’s the sex offender who happened to be visiting Nanna’s school on the day of her disappearance. There’s the wild pupil with an unrequited love for her and a sinister underground sex den. There’s the teacher with the teen-porn habit and the other teacher with complaints on his record about harassment. There’s the ambitious mayoral candidate with a puzzling blank in his diary for the night of the abduction, and numerous others besides.

On its way, The Killing deploys almost every available crime cliché: the apparently wholesome murder victim who is revealed to have a Laura Palmer-like dark side; the scene where the compromised police chief warns the detectives to ‘stay well away from City Hall,’ though the clues lead straight to it; the scene where a hidden door is discovered leading to a secret room (twice); the scene where the detective has to surrender her badge because she’s gone rogue; the scene where she gets it back again because she was right. The series has been compared to Season 3 of The Wire, because it features a mayoral election and a crime story, but it’s nothing like that. It’s Agatha Christie writ large across Copenhagen; or, as my wife put it, like the best episode of Taggart you’ve ever seen, lasting 20 hours. This is not a criticism. Detective fiction is a conventional form, and it’s hard to imagine it otherwise. Where would we all be without such traditional plot devices as the moment when the police technician zooms in on the grainy CCTV footage, to reveal a shockingly unexpected face? And in most cases, The Killing gives the clichés a novel turn of the screw. For instance, the detective and sidekick double-act is a good one: the ostensibly hippyish liberal Lund is paired with Jan Meyer, a crisp-eating, chain-smoking hick with a good line in off-colour jokes (Lund: ‘Why didn’t you get me a hamburger?’ Meyer: ‘I thought you only liked Swedish sausage.’)

Where The Killing does buck the norm is in its unusually slow pace, and its strong interest in the characters – particularly the girl’s mourning family and Troels Hartmann, the mayoral candidate. Nanna’s parents, Theis and Pernille (a strong, silent removal man and his strong and slightly less silent wife), are a major focus of the story. The funeral arrangements, the arguments, the bereavement therapy and the effect on their other children are all movingly portrayed. Danish TV has apparently been much influenced by the Dogme manifesto, Lars von Trier’s vows of stylistic ‘chastity’. In The Killing, car chases are chucked out in favour of grimy night-time location shots – dingy industrial estates and the edgelands by Copenhagen airport. The camera is often handheld. The acting is naturalistic, and excellent. Sophie Gråbøl has somehow mastered the art of being fascinating to watch while giving hardly anything away (Bjarne Henriksen and Ann Eleonora Jørgensen, playing Theis and Pernille, are also virtuoso exponents of wordless acting). Gråbøl, one of Denmark’s leading actresses, is very pretty but also lined and interesting, like a cross between Jenny Agutter and Greta Scacchi. She sets the tone for the rest of the cast, who tend to be good-looking but in a vaguely plausible way, so that you can just about imagine meeting them in real life. As Troels, Lars Mikkelsen (brother of Mads Mikkelsen, the bloody-eyed master villain in Casino Royale) is genuinely charismatic, flitting between idealism and ruthlessness. And Søren Malling’s Jan Meyer, with his solemn face and big ears, is always good value.

For British audiences, the Danish detail provides a lot of incidental charm. The general style is the now well-established ‘Nordic noir’: a tone of poetic bleakness, as the seamy underbelly of yet another nice social democracy is enjoyably laid bare. The Killing is positively heroic in its determination to make Copenhagen’s municipal politics seem cut-throat and corrupt – I don’t believe it for a second – as Troels and his opponents fall out viciously over environment, housing and integration policies. Then there are the lovely interiors. The characters all seem to have beautiful kitchens, matched carefully to their characters. Troels’s is flash and a bit heartless; Pernille’s is the opposite, with some really excellent glassware; Lund’s grumpy mum’s kitchen, where her daughter is often seen eating cold leftovers late at night, is tasteful in an old-fashioned, slightly chilly way, like a Hammershøi painting. Even the prisons look quite nice. The language is also great fun to listen to: very alien sounding, with strangulated gutturals and long open vowels – ‘Troels’ and ‘Larsen’ – but at other times very much like English. The slightly silly pulsing Euro-electro soundtrack, with occasional New Agey wailing, is another highlight, as are the Danish jokes about the Swedish: the mere mention of the Swedes and their funny names is often enough to make the characters break out in giggles.

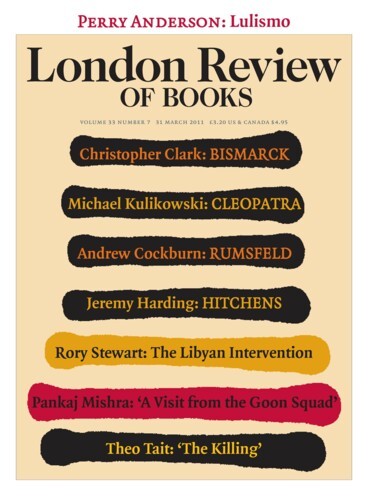

Most of all, though, The Killing is an awesome feat of narrative engineering. I’ve never seen a single mystery plot sustained for so long before, except in Twin Peaks, which was a bit different. And the series does it in a way that is both formulaic and extremely effective. There’s usually one big plot point – an incident that spins the action around into an entirely new direction – per episode. Some of these revelations are better than others, but they reliably blindside the audience, and they are always exciting and expertly choreographed. And all the while, three separate narrative lines – family, police and politics – are woven together, each filled with rich, believable characters. Writing with four more episodes to go, I am genuinely in the dark as to where things are heading: there’s one obvious suspect, and perhaps another two behind him, Russian doll-style, but I am fully expecting one or two shocking twists before the end. (During filming, even the actors weren’t told who the murderer was until it was absolutely necessary.) Finales are always the most difficult part of a detective story. The promise to solve a mystery is a powerful narrative propellant, and when it is exchanged for the final revelation, one often feels short-changed. But The Killing screenwriter, Søren Sveistrup, has promised a ‘biblical’ ending: ‘It’s more than you have seen before, trust me.’ I have no reason to disbelieve him.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.