Bedbugs never went away. DDT gave them a hard time in the 1940s and for years afterwards, until Rachel Carson’s campaigns outlawed it, but resistant strains survived. Other insecticides – synthetic organophosphates and pyrethroids – have come and gone, but none has been a challenge for the bugs’ versatile genomes. Blood is their only food. The bug explores the skin of its victim with its antennae. It grips the skin with its legs for leverage, raises its beak, and plunges it into the tissues. It probes vigorously, tiny teeth at the tip of the beak tearing the tissues to forge a path until it finds a suitable blood vessel. A full meal takes 10 to 15 minutes. A hungry bug is squat and flat like a lentil. When replete, its distension shapes it like a long berry. A bug will feed weekly from any host that is handy.

Bedbugs do not spread disease. Their presence has been taken as an indicator of poor home hygiene, and they can be a precipitant of entomophobia, but beyond that they haven’t had much significance for public health. Nobody counts them or keeps national records of infestation rates. There are hardly any 20th-century baseline measures that might enable us to assess the accuracy of claims that there has been an upsurge in the 21st. Anecdote has driven the perception that the bugs have gone on the rampage, and epidemiologists are reluctant to put much weight on stories. But the recent ones have been very persuasive. In New York in 2010 bedbugs turned up in the Empire State Building, a theatre in the Lincoln Center, and at the Metropolitan Opera House. It is said that they were in attendance at the 2005 Labour Party Conference in Brighton, and in 2006 they were found in a guest room at the five-star Mandarin Oriental Hyde Park Hotel in Knightsbridge. Analyses shows that the number of bedbug calls to pest controllers in London and Australia has increased significantly since 2000.

Why the resurgence? The bugs’ resistance to insecticides has been blamed, along with the increase in international travel and in the sale of second-hand furniture. Genetic fingerprinting of the bugs might shed light on the comparative importance of movement from city to city, travel across national boundaries and purely local spread; but such studies have only just started. In truth our understanding of how bedbugs get about has changed little since 1730, when John Southall published his Treatise of Buggs:

By Shipping they were doubtless first brought to England, so are they now daily brought. This to me is apparent, because not one Sea-Port in England is free; whereas in Inland-Towns, Buggs are hardly known … If you have occasion to change Servants, let their Boxes, Trunks, &c. be well examin’d before carried into your Rooms, lest their coming from infected Houses should prove dangerous to yours … Upholsterers are often blamed in Bugg-Affairs; the only Fault I can lay to their Charge, is their Folly, or rather Inadvertency, in suffering old Furniture, when they have taken it down, because it was buggy, to be brought into their Shops or Houses, among new and free Furniture, to infect them.

Southall’s worries about the role of ships in transporting bedbugs persisted. Robert Usinger, the author of the monumental Monograph of Cimicidae (the family to which the bedbug belongs), saw a thriving colony of the tropical bedbug, Cimex hemipterus, on a liner sailing from Hong Kong to San Francisco. But local transport is just as much of a problem. In 1944, Usinger was bitten by the common bug, Cimex lectularius, on a bus in Atlanta, Georgia. And in the summer of 1947 a number of ladies in Dundee were referred to the local dermatologist because they had developed a red band studded with blisters, some described as being ‘as big as a pigeon’s egg’, on the backs of their calves. All of them had travelled on the lower deck of a tram on the same route. Investigation showed that only one tram was infested. The bugs had settled in a groove in a wooden slat that held a seat in place. They sat in a row on the edge of the wood, the dermatologist said, ‘extracting nourishment from the legs of unsuspecting lady passengers. Men were never affected, their stouter nether garments providing sufficient protection. The tram was disinfected, the grooves were planed out … the epidemic came to an end.’

In 2008, bugs were found on the New York subway, on wooden benches on station platforms at Hoyt-Schermerhorn in Brooklyn, Union Square in Manhattan and Fordham Road in the Bronx, and in 2010 in a booth at Ninth Street Station on the D Line. ‘If you put out your Linnen to wash,’ Southall said, ‘let no Washer-woman’s Basket be brought into your houses; for they often prove as dangerous to those that have no Buggs.’ The Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service has found bedbugs at airports in woven cane baskets and woven straw bags – as well as on roses from Kenya, in baggage from Europe, and on an airport inspection bench.

So it is clear that bedbugs can hitch-hike long distances and ride about town. But how good they are at very local travel remains undetermined. Urban myths have been around for a long time. ‘Bedbugs are popularly credited with an amazing amount of intelligence,’ observed the British Ministry of Health’s ‘Report on the Bedbug’ in 1934. ‘It is stated that they will travel long distances, 50 yards or more, in search of food, will unerringly choose the direction in which their food is to be found, will go by way of windows, eaves and gutters if unable to get through the party wall, and will drop from the ceiling onto their victims. We are not prepared to say how much of this may be due to popular superstition.’ The report was produced because ‘the infestation of new council houses has become a matter of concern to Local Authorities who are responsible for their maintenance and management.’ Whether bugs became common in these council houses is not clear; it is certain, however, that the current upsurge in bedbug numbers cannot be blamed on an increase in social housing stock.

Hundreds of scientific papers have been published on bugs, though funding for bug research has never been easy to get because of their medical unimportance. Surveys of prevalence are expensive and are hardly ever done. But bugs are easy to keep in the laboratory. Some investigators have allowed bugs to feed on them for convenience, and to save money. Much attention has been paid to their method of reproduction. Males mate preferentially with recently fed females. The male sexual organ, called the paramere, has a sharp point, which the male bug uses to penetrate the abdominal wall of the female. Sperm are injected into the abdominal cavity. This process is sometimes lethal; repeated matings reduce the female lifespan. This sexual conflict of interests has been of great interest to evolutionary biologists.

Males attempt to mate with any moving object the size of a fed female, including juvenile bugs and males who have sucked blood. But in these cases they dismount quickly – good news both for the male, who doesn’t waste his sperm, and for the mountee, since penetration would quite likely have perforated his guts to mortal effect. The males back off because inappropriate partners produce chemical deterrents – alarm pheromones. Their smell is easily detected by humans. It has been described as an ‘obnoxious sweetness’, and is characteristic of a bedroom with a heavy infestation. It is highly likely that these pheromones are what the bedbug-sniffer dog detects. Two firms in Florida train them, usually using animals rescued from shelters. One firm prefers beagle mixes, the other labrador retriever mixes. Bold claims are made for their success. New York City is hiring two, and Lola, a Jack Russell bitch, has been imported into the UK.

Bedbugs avoid the light and are thigmotactic: they love contact with rough surfaces. They seek cracks and crevices, preferably in wood or paper, in which they establish refugia to digest their meals and breed, among an accumulation of faeces, egg shells and cast-off skins. Bugs in refugia are hard to reach with pesticides. Drastic measures have been used. A note in the Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1926 entitled ‘Disinfestation of Barracks’ records that the British Army of the Rhine had been contacted by the representative of a firm in Frankfurt am Main who wanted to explain the use of a substance with the trade name Zyklon ‘B’. He described it as ‘siliceous earth impregnated with hydrogen cyanide, to which is added a tear gas’, and noted that it was extensively used by the German government. A large advertisement inside the front cover of the standard German work on bedbugs published in 1936 says: ‘Zyklon and T-Gas exterminates bugs … without damaging the furnishings.’

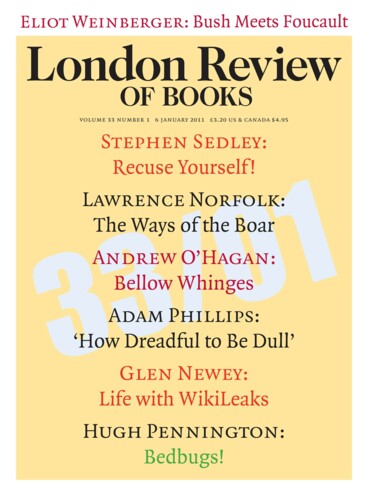

The current upsurge has been good news for pest controllers. Booksellers have benefited too: a copy of Southall’s 44-page treatise was auctioned by Bonhams at Oxford in October 2010, and despite being disbound, lacking a frontispiece and having numerous ink annotations, went for £132 inclusive of the buyer’s premium. And bugs have brought business to lawyers. The landmark case this century has been Mathias v. Accor Economy Lodging Inc. The plaintiffs, Burl and Desiree Mathias, were bitten by bugs while staying at a Motel 6 in downtown Chicago. They claimed that in allowing guests to be attacked by bedbugs in rooms costing upwards of $100 a day, the defendant was guilty of wilful and wanton conduct. The jury awarded each plaintiff $5000 in compensatory damages and $186,000 in punitive damages. The defendant appealed, complaining primarily about the level of the punitive damages, but the appeal court judge, Richard Posner, dismissed the appeal. His decision was bold: a Supreme Court statement had been made not long before that ‘few awards exceeding a single-digit ratio between punitive and compensatory damages, to a significant degree, will satisfy due process.’ Posner noted that bedbugs had been discovered at the motel in 1998 by EcoLab, an extermination service. They recommended that every room be sprayed, at a cost of $500. The motel refused. Bugs were found again in 1999. The motel tried without success to get an exterminator to sweep the building free of charge. In the spring of 2000 the motel manager told her superior that guests were being bitten and were demanding, and receiving, refunds, and recommended that the motel be closed while every room was sprayed. Her boss refused. On one occasion a guest was moved from a room after being bitten, only to discover insects in the second room; then, within 18 minutes of being moved to a third, he found them there as well. ‘Odd that at that point he didn’t flee the motel,’ Posner comments. He was unimpressed by the instruction given to desk clerks by the motel management that bed bugs should be called ticks, ‘apparently on the theory that customers would be less alarmed, though in fact ticks are more dangerous than bedbugs because they spread Lyme Disease and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever’. This is the bedbug paradox. For most individuals their bites have only nuisance value. Yet they arouse much more disgust than many other insects whose bites transmit potentially lethal infections.

The bugs in the Empire State Building, Lincoln Center Theater and the Met were found in the basement employee changing room, a dressing-room, and back of house. The likelihood of being bitten in a public place without beds is remote. And if the New York subway had the London Tube’s metal seats rather than wooden ones there would be no bug refugia. Alleviation here would be easy. But it is unlikely that the public will come to terms with bugs. They will continue to turn to lawyers. Posner’s judgment and its financial consequences are on record.

The bedbugs’ lifestyle makes it unlikely that they will go away soon. The contrast with the body louse is instructive. Their refugia and breeding places are the seams of human clothing. Body heat is necessary for egg hatching, so those who take their underclothes off at night and change their garments more than once a month will never be very lousy even if they consort with those who are. The natural habitat of the bedbug is the home. In Europe and North America the only one left for the body louse is the homeless.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.