Sweeney, in Eliot’s Sweeney Agonistes, says he’ll carry Doris off to a cannibal isle (she’s unimpressed). There will be:

Nothing to hear but the sound of the surf.

Nothing at all but three things.

DORIS: What things?

SWEENEY: Birth, and copulation, and death. That’s all, that’s all, that’s all, that’s all. Birth and copulation and death.

DORIS: I’d be bored.

Later the island is praised, in a parody of a popular song, as a place

Where the Gauguin maids

In the banyan shades Wear palm leaf drapery

Under the bam

Under the boo

Under the bamboo tree.

For Sweeney, Gauguin’s women represent the crudest version of the myth of island bliss. But you don’t have to look long at Gauguin’s work (a retrospective is at Tate Modern until 16 January) to realise that bliss is not the subject of his Tahitian pictures. Idols in the shadows announce a world explained by tales of frightening gods, spirits and ghosts. The translations of the Tahitian titles Gauguin wrote on the canvases – Brooding Woman, The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch, Why Are You Angry?, What! Are You Jealous? – speak of island lives that are as troubled as any. Gauguin maids, the solemn, solid, bare-breasted, brown girls surrounded by flowers, fruit, trees and the sea, may have entered the popular imagination as images of blissful indolence but a closer look tells you that the pictures are sad. (In a letter to his wife, Mette, he once described the ‘harmony’ of his colours as ‘sombre, sad, frightening’.)

Although his pursuit of primitive art, life and mythology – Breton or Polynesian, Christian or pagan – was integral to his notion of what he was doing, it illuminates the pictures only fitfully. His power as a painter and his influence on his contemporaries and later generations had more to do with colour and drawing than with the myths. Tahiti, the Marquesas and Brittany matter of course; his strength and imaginative reach cannot be separated from his subject-matter. But of the Symbolists, it is those like Gauguin and Munch, whose myth is personal, whose pictures resist explicit interpretation or baffle those in search of it, that have worn well. No body of work in the period that saw the transformation of art from a commentary on what we see to the creation of imagined or transmuted worlds is so full of hints about what could and did follow. That the idea of a Gauguin maid spread easily beyond the world of high art was an early sign that modern art can become popular art.

Gauguin’s ‘primitive’ way with colour has now become so pervasive that it’s hard to remember that a pink horse or a blue one was once thought to be risible. Areas of unmixed red, blue, green and yellow take on a life of their own, as the gilded backgrounds and blue cloaks of medieval madonnas do, or the pure colours of Indian miniatures. Bring one of his pictures to mind and it is often a patch of strong colour that you remember first: the vermilion field on which Jacob wrestles with the angel in Vision of the Sermon. Pink sand in What! Are You Jealous? The lemon-yellow pillow the girl lies on in Nevermore. The orange foliage and yellow flesh in Yellow Christ. The plum reds and near blacks in still-lifes, the deep greens, pinks and thunderous purples in landscapes. It was a step on the path that led to the Fauve freeing up of the relation between colour and natural appearance that would blossom more beautifully, but in some ways less richly, in Matisse.

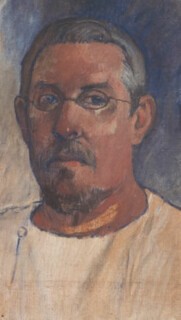

References tucked into the backgrounds of still-lifes and portraits seem to be evidence of a need to place himself in relation to his own art and that of others, to record who he was and where, artistically, he was coming from. An 1889 self-portrait with snake and apples (as Lucifer?), and one from 1890 with both the Yellow Christ and his stoneware Self-Portrait in Form of Grotesque Head in the background, announce the self-proclaimed savage. (The second of those paintings belongs to the Musée d’Orsay and isn’t in the exhibition.) In two self-portraits of 1893, the year he returned to Paris and exhibited Tahitian pictures to critical approval, there are details that establish the Polynesian connection: an idol in the background of one and his own painting, The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch, in the background of the other. Only in the last self-portrait, painted in 1903, the year of his death, do you stop feeling that you are being presented with a chosen persona. He has turned to face you, now wears spectacles and looks beaten. He will go on fighting but the bravo has become a sick beachcomber.

There are still-lifes here that carry references of much the same sort. One of fruit, in which a sketch by Delacroix emerges from the top margin; one of peonies with a Degas dancer sitting with her legs apart in the top corner; another of sunflowers with one of his own Tahitian portraits in the right margin. He seems to be saying: ‘Keep in mind the work of my admired colleague Delacroix, who also pursued the exotic, remember our splendid contemporary Degas, who made the natural pose powerful.’ Faces, too, intrude from the margins: that of an elf-like slant-eyed child in one, the painter Charles Laval in another. The deeply traditional subject-matter of fruit and flowers becomes the foreground to unexplained anecdotes or fables.

There is a lot of his carving and ceramic work in the exhibition in which the overtly primitive idols in the background of his paintings step forward. Few handsome girls figure among them, and when you find one that is also in a picture (itself derived from a photograph) the Gauguin maid becomes something darker and heavier. Given the quality of the exhibition and its impressive range, it’s a pity that the essays in the catalogue – ‘Paul Gauguin: Navigating the Myth’, ‘Gauguin and the Opacity of the Other: The Case of Martinique’ and so on – don’t give all the mundane but revealing information you would normally find in item by item entries. What information there is, you get by scuttling through the chronology and index.

The exhibition’s subtitle is ‘Maker of Myth’. The suggestion seems to be that we have to get past common misconceptions and pay more attention to the complexity of the narratives he created and manipulated. But that kind of exegesis isn’t necessarily useful. The best of the paintings have a life of their own, and while our perception of them doubtless changes with cultural fashion, it is uncomplicated and direct: fear in a girl’s face, the yellow pillow she lies on, the vertigo that comes over you when you see the cow on a cliff in Over the Abyss, the blue shadows on the pink sand – these things are like simple sentences, easy to read, and very easy to like and admire.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.